For Jordan and other Black feminists, poetry was not just an individual exercise but a “social act,” a form of collective and personal resistance. Jordan sought to nurture an active partnership between writer and reader, which she actualized in P4P classes. The students in these classes published anthologies and hosted readings to share their voices and perspectives with one another and a wider community. Under the leadership of director Aya de León in the Department of African American Studies & African Diaspora Studies, the program carries on in Jordan’s spirit.

For her, poetry is a social act

By Mickey Friedman

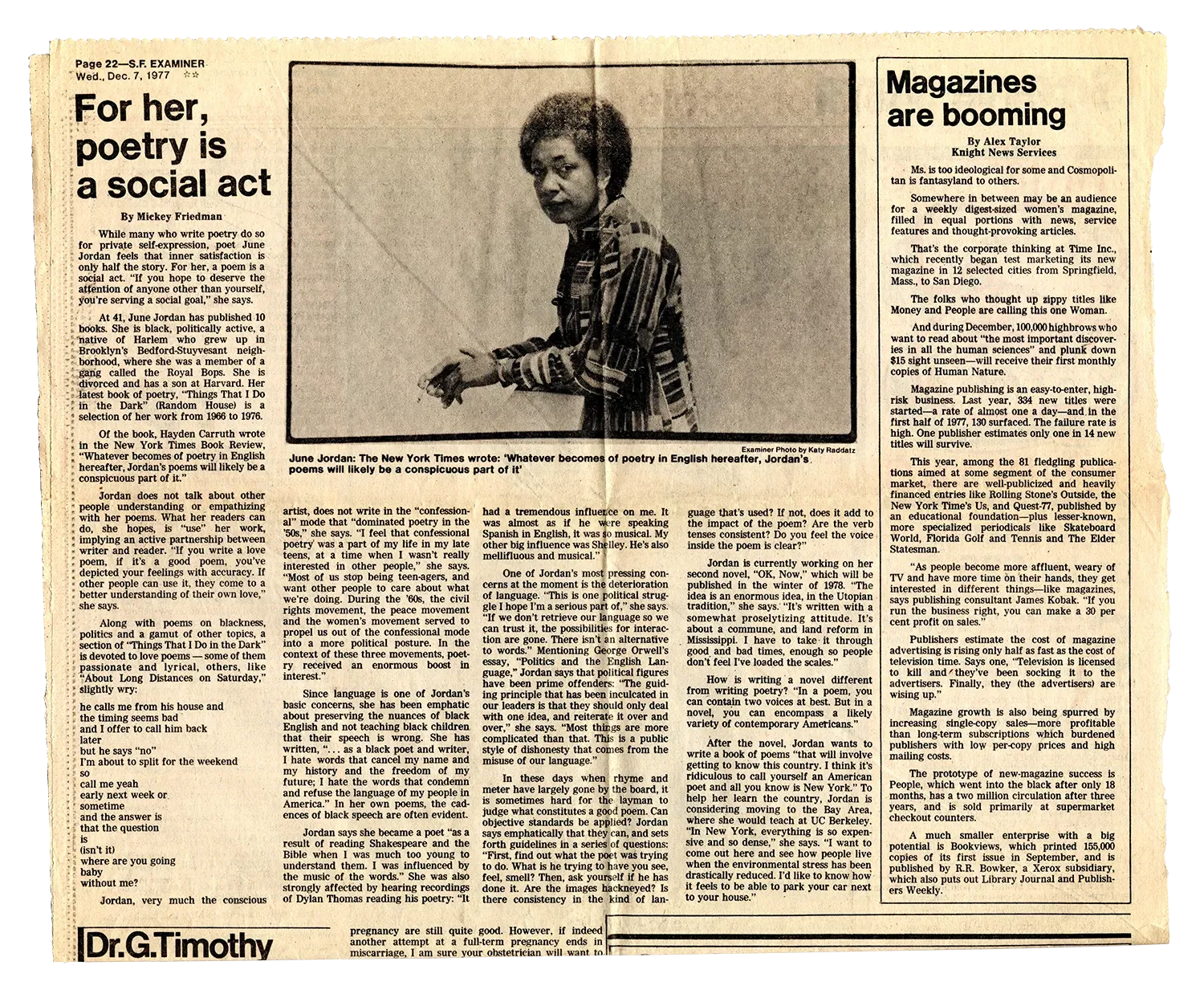

Examiner Photo by Katy Raddatz

(Image description) June Jordan is seen in front of a chalkboard, looking toward the camera.

(Image caption) June Jordan: The New York Times wrote: ‘Whatever becomes of poetry in English hereafter, Jordan’s poems will likely be a conspicuous part of it’

While many who write poetry do so for private self-expression, poet June Jordan feels that inner satisfaction is only half the story. For her, a poem is a social act. “If you hope to deserve the attention of anyone other than yourself, you’re serving a social goal,” she says.

At 41, June Jordan has published 10 books. She is black, politically active, a native of Harlem who grew up in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, where she was a member of a gang called the Royal Bops. She is divorced and has a son at Harvard. Her latest book of poetry, “Things That I Do in the Dark” (Random House) is a selection of her work from 1966 to 1976.

Of the book, Hayden Carruth wrote in the New York Times Book Review, “Whatever becomes of poetry in English hereafter, Jordan’s poems will likely be a conspicuous part of it.”

Jordan does not talk about other people understanding or empathizing with her poems. What her readers can do, she hopes, is “use” her work, implying an active partnership between writer and reader. “If you write a love poem, if it’s a good poem, you’ve depicted your feelings with accuracy. If other people can use it, they come to a better understanding of their own love,” she says.

Along with poems on blackness, politics and a gamut of other topics, a section of “Things That I Do in the Dark” is devoted to love poems — some of them passionate and lyrical, others, like “About Long Distances on Saturday,” slightly wry:

he calls me from his house and

the timing seems bad

and I offer to call him back

later

but he says “no”

I’m about to split for the weekend

so

call me yeah

early next week or

sometime

and the answer is

that the question is

(isn’t it)

where are you going

baby

without me?

Jordan, very much the conscious artist, does not write in the “confessional” mode that “dominated poetry in the ’50s,” she says. “I feel that confessional poetry was a part of my life in my late teens, at a time when I wasn’t really interested in other people,” she says. “Most of us stop being teen-agers, and want other people to care about what we’re doing. During the ’60s, the civil rights movement, the peace movement and the women’s movement served to propel us out of the confessional mode into a more political posture. In the context of these three movements, poetry received an enormous boost in interest.”

Since language is one of Jordan’s basic concerns, she has been empathetic about preserving the nuances of black English and not teaching black children that their speech is wrong. She has written, “… as a black poet and writer, I hate words that cancel my name and my history and the freedom of my future; I hate the words that condemn and refuse the language of my people in America.” In her own poems, the cadences of black speech are often evident.

Jordan says she became a poet “as a result of reading Shakespeare and the Bible when I was much too young to understand them. I was influenced by the music of the words.” She was also strongly affected by hearing recordings of Dylan Thomas reading his poetry: “It had a tremendous influence on me. It was almost as if he were speaking Spanish in English, it was so musical. My other big influence was Shelley. He’s also mellifluous and musical.”

One of Jordan’s most pressing concerns at the moment is the deterioration of language. “This is one political struggle I hope I’m a serious part of,” she says. “If we don’t retrieve our language so we can trust it, the possibilities for interaction are gone. There isn’t an alternative to words.” Mentioning George Orwell’s essay, “Politics and the English Language,” Jordan says that political figures have been prime offenders: “The guiding principle that has been inculcated in our leaders is that they should only deal with one idea, and reiterate it over and over,” she says. “Most things are more complicated than that. This is a public style of dishonesty that comes from the misuse of our language.”

In these days when rhyme and meter have largely gone by the board, it is sometimes hard for the layman to judge what constitutes a good poem. Can objective standards be applied? Jordan says emphatically that they can, and sets forth guidelines in a series of questions: “First, find out what the poet was trying to do. What is he trying to have you see, feel, smell? Then, ask yourself if he has done it. Are the images hackneyed? Is there consistency in the kind of language that’s used? If not, does it add to the impact of the poem? Are the verb tenses consistent? Do you feel the voice inside the poem is clear?”

Jordan is currently working on her second novel, “OK, Now,” which will be published in the winter of 1978. “The idea is an enormous idea, in the Utopian tradition,” she says. “It’s written with a somewhat proselytizing attitude. It’s about a commune, and land reform in Mississippi. I have to take it through good and bad times, enough so people don’t feel I’ve loaded the scales.”

How is writing a novel different from writing poetry? “In a poem, you can contain two voices at best. But in a novel, you can encompass a likely variety of contemporary Americans.”

After the novel, Jordan wants to write a book of poems “that will involve getting to know this country. I think it’s ridiculous to call yourself an American poet and all you know is New York.” To help her learn the country, Jordan is considering moving to the Bay Area, where she would teach at UC Berkeley. “In New York, everything is so expensive and so dense,” she says. “I want to come out here and see how people live when the environmental stress has been drastically reduced. I’d like to know how it feels to be able to park your car next to your house.”

Page 22—S.F. Examiner

Wed., Dec. 7, 1977

“For her, poetry is a social act,” by Mickey Friedman, San Francisco Examiner, 1977, Carton 6:50, Barbara Christian papers, BANC MSS 2003/199 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.