JACK VON EUW was at the bookstore at the Museum of the African Diaspora, in San Francisco, when he saw David Johnson’s book for the first time.

“I looked at the book, and I was totally intrigued,” says von Euw, pictorial curator at The Bancroft Library.

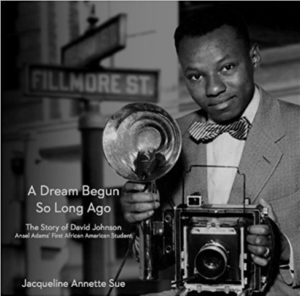

A Dream Begun So Long Ago was written by Jacqueline Annette Sue, David Johnson’s wife.

The book was 2012’s A Dream Begun So Long Ago, by writer Jacqueline Annette Sue, Johnson’s wife, about her photographer husband’s life — and it was filled with Johnson’s work.

“The story and the photographs just grabbed me,” von Euw says.

“I’ve got to have this,” he remembers thinking to himself.

In the meantime — call it serendipity — Dorothy White, a friend of Johnson’s, gave a letter to Tom Leonard, the university librarian at the time, who passed it on to von Euw.

“Would the University Library be interested in Johnson’s work?” von Euw recalls the letter asking.

Von Euw contacted White, who lives in the same retirement community as Johnson and his wife, and she introduced him to the photographer.

And so began a conversation that culminated in 2016 with The Bancroft Library acquiring the archive of Ansel Adams’ first African American student. Johnson, now 91, is the first African American photographer whose archive is represented at Bancroft.

The collection, consisting of about 5,000 negatives and photographic prints, is significant for several reasons. Not only are Johnson’s photographs “beautifully composed,” von Euw says, they’re historically significant, documenting the social conditions of African Americans and the attempt to gain equal rights. In many cases, Johnson’s familiarity with his subjects afforded him a level of access that allowed him to capture moments and people from a perspective that otherwise would go unseen.

“It’s one of the best documentaries I have seen of an African American community,” von Euw says of the archive.

“We have a lot of amazing work — some by renowned photographers,” he says. “I thought his work would be a perfect fit.”

‘A burning desire’

Johnson remembers his first contact with Ansel Adams.

After returning to his native Jacksonville, Florida, after a stint in the Navy (he was drafted before he finished high school), Johnson ran across a magazine article that mentioned the California School of Fine Arts, in San Francisco, was establishing a photography department, which Adams would lead.

Johnson joined the U.S. Navy after he was drafted while still in high school. (Courtesy of David Johnson)

Johnson sent Adams a message.

“I said, ‘Dear Mr. Adams: I’m interested in studying photography. … By the way, I’m a negro,’” Johnson recalls in a recent interview.

Then came Adams’ response. The class was full, he said, but Johnson would be put on a waiting list.

Johnson recalls the life-changing telegram from Adams that came later: “There’s a spot for you, David, if you want to proceed.”

Growing up in segregated Jacksonville, Johnson’s opportunities had been limited. He was raised by a relative, Alice Johnson — from whom he took his last name — in a household where he was the only one who could read or write.

“There was nothing to hold me in Jacksonville, Florida,” Johnson says.

And so he left The Sunshine State, arriving in San Francisco with his equipment — an Eastman folding camera he had bought for $5 — and no formal training in photography.

“I didn’t have that background,” he says. “What I had was a burning desire to study photography and succeed.”

In the Bay Area, Johnson was embraced by the faculty and classmates at the California School of Fine Arts.

Adams put Johnson up in his Richmond district home until Johnson could find another place to stay. Johnson recalls arriving at the house, which felt, he says, like “the beginning of a phenomenal journey.”

Minor White, seen in this photo by Johnson, was one of the celebrated photographers who taught at the California School of Fine Arts.

“I felt welcome,” he says. “I was one of the family.”

Johnson remembers an early conversation with Minor White, one of the distinguished photographers who taught at the school — and who also lived in Adams’ home.

“Where’s your camera?” Johnson remembers White asking.

Johnson showed White his Eastman folding camera.

“I don’t think that’s going to work,” White said, as Johnson recalls.

Then came a surprise a few days later.

“They put their money (together) to buy me a new camera,” Johnson says. “They wanted me to succeed.”

A legacy of photos

In San Francisco, Johnson became part of the so-called Golden Decade, a group of students who studied at the California School of Fine Arts — now known as the San Francisco Art Institute — under such luminaries as Adams, White, Imogen Cunningham, and Dorothea Lange. Many from that group, like Johnson, went on to establish successful careers of their own.

By the time Johnson arrived in San Francisco, the Great Migration — the exodus of African Americans from the rural South to cities in the North and the West — was well underway. Like Johnson, they had come to invest in a better future.

Looking South on Fillmore is one of Johnson’s most iconic photographs.

As the African American population of San Francisco swelled during World War II, many took up residence in the Fillmore district.

“They became my friends, and they became my neighbors,” Johnson says. “And they became my subjects.”

The neighborhood appears in one of von Euw’s favorite photographs by Johnson: Looking South on Fillmore, made in 1946.

It’s impeccably composed, with diagonals that draw in the viewer, he says. To make the iconic image, Johnson climbed on a scaffold, capturing the bustle of pedestrians and a streetcar as it glided through the frame.

“It’s probably the best record of what the Fillmore after the war looked like,” von Euw says.

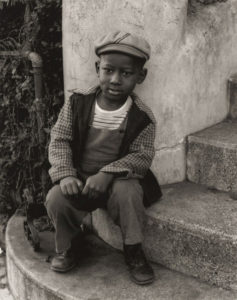

Johnson’s personal favorite was also made in the Fillmore. It’s what he considers his signature photograph: Clarence, a 1947 image of a young boy in overalls, sitting on church steps. The boy, like Johnson, was raised by a relative and had a “certain innocence,” Johnson recalls.

Johnson says this image, called Clarence, is his personal favorite.

“There was something about this little boy,” he says. “I could see myself in him.”

After graduating from the California School of Fine Arts in 1949, Johnson opened up a photo studio on Divisadero Street, supplementing his income with a job at the post office and photography work for the Sun-Reporter newspaper.

In addition to his photographs documenting the lives of ordinary residents, Johnson turned his lens to many notable figures, including politicians, protesters in the March on Washington, and players in the neighborhood’s bustling jazz scene. Johnson’s subjects have included musicians Nat King Cole, Eartha Kitt, and T-Bone Walker; poet Langston Hughes; Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall; and baseball great Jackie Robinson.

Over the years, Johnson’s photos have popped up in numerous places: books, exhibits, and, notably, local TV station KQED’s documentary The Fillmore, chronicling the neighborhood’s history.

So indelible is his connection with the Fillmore that today, his name is etched in concrete in Gene Suttle Plaza, in the neighborhood that serves as the backdrop for many of his photographs.

Among the many musicians Johnson photographed was Nat King Cole, seen here at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco.

These days, photography is still part of Johnson’s life. He has held on to his Eastman folding camera throughout the years, but now he’s more likely to take photos with his iPhone. He also spends time talking to young students in Oakland, telling them about his life, passing on his wisdom, and inspiring them to achieve their dreams, as he has achieved his.

“It really is an amazing story of someone who had the will, the vision, the perseverance to transform his life completely under what were really constrained circumstances,” von Euw says.

How does Johnson feel now, after looking back on that “phenomenal journey” he embarked on all those years ago?

“I feel comfortable, I feel good, I feel blessed,” he says. “At 91 years old, I’ve lived a good life.”

[David Johnson photograph archive], BANC PIC 2017.001. © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.