Stand Up and Say Something

During these times of distress, we need to know that our voices are heard. As part of the UC Berkeley Library community, we must respond with both our intelligence and our hearts. Protests against police brutality and racial violence erupt around us, echoes of the historical injustices and race riots of decades past. History has shown us that we have the power to transform our communities, including our work environment. As an organization, showing our intolerance toward racism is essential. Together with the Library’s systemwide response, we have created this informal publication — a zine — to inspire organizational awareness and empathy for our communities of color and allies. A compilation of photos, essays, illustrations, song lyrics, poetry, and video from staff members across the Library, Stand Up and Say Something raises our collective voice against systemic discrimination and explores how our actions shape us as individuals, and as an organization. Stand Up and Say Something is our call to action.

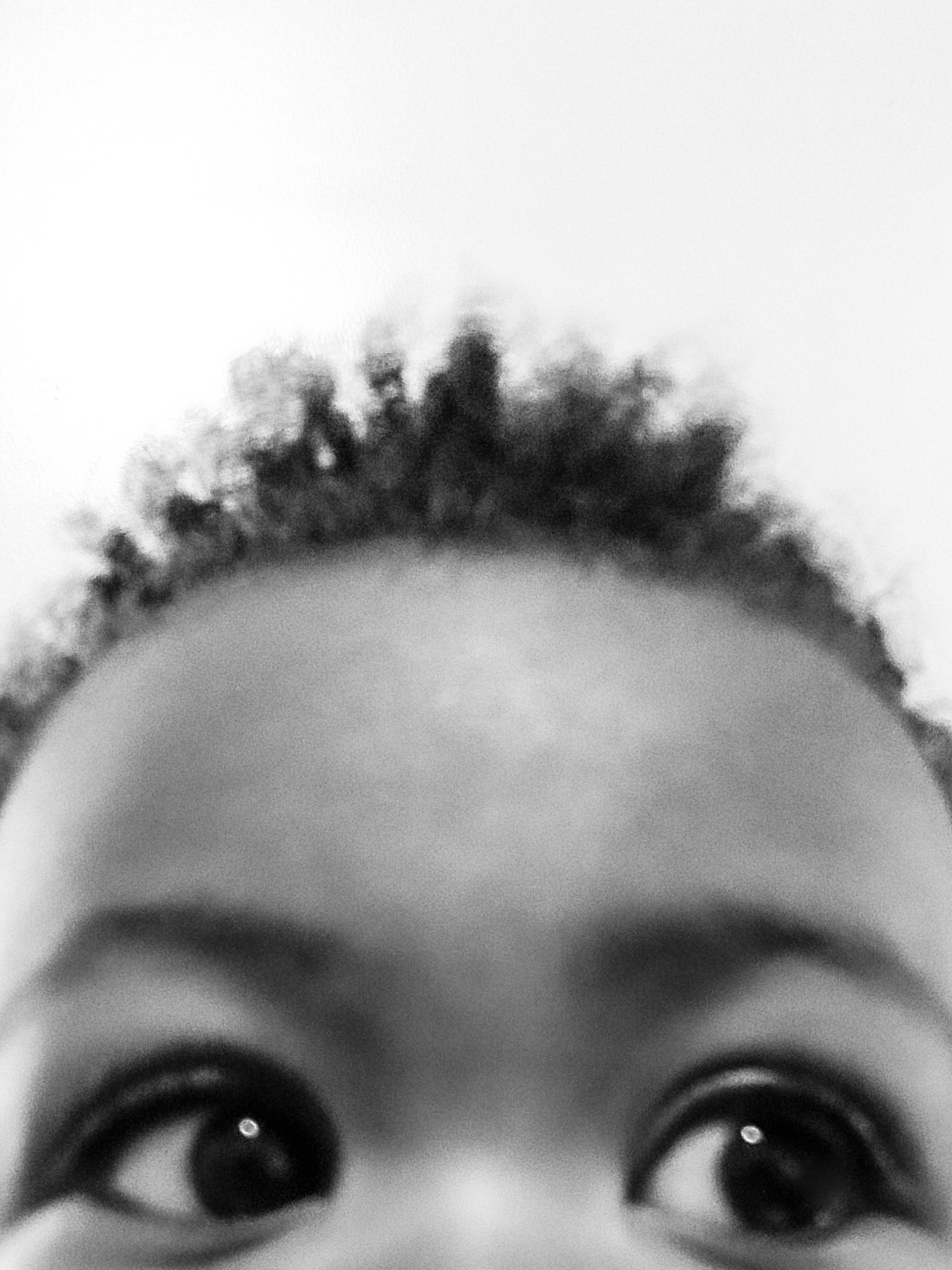

Shannon L.

Monroe

Interlibrary Services

“How Are You?”

June 2020

Motivated

Loved

Liked

Joyful

Blessed

Fortunate

Resourceful

Determined

Supported

Ambitious

Intelligent

Encouraged

Powerful

Eager

Excited

Black

Enraged

Anxious

Nervous

Hunted

Frustrated

Exhausted

Disrespected

Hated

Aggrieved

Suspicious

Prejudged

Discounted

Disgusted

Numb

Assaulted

Murdered

Michele

Buchman

Life & Health Sciences Division

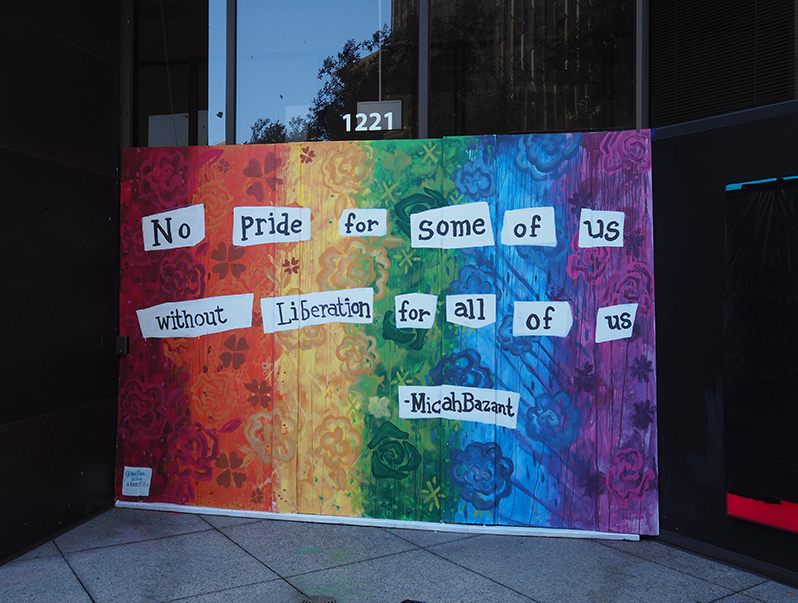

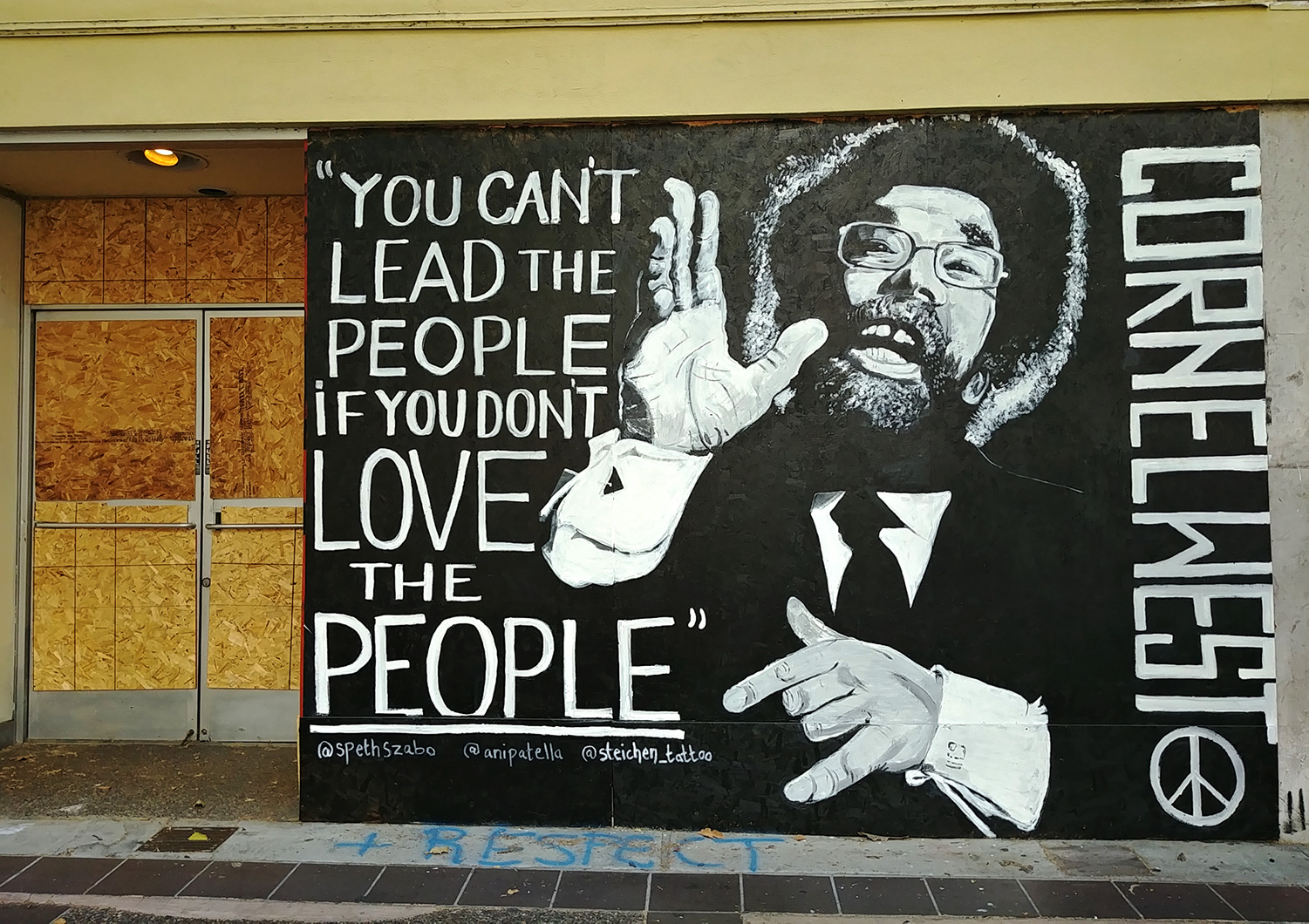

Images from the Oakland Streets

June 9, 2020

In the days immediately following the recent demonstrations in Oakland, amazing artwork appeared on boarded-up storefronts along Broadway. In sharing these images I’m hopeful their impact will be felt more broadly, because even if these boards are dismantled in time, the message that has found collective strength and expression on our streets will not be.

Murals on Broadway

37° 48’ 10.584’’ N, 122° 16’ 19.452’’ W — 37° 48’ 23.94’’ N, 122° 16’ 10 .992’’ W

12th and Broadway — 17th and Broadway, Oakland

Photos by Michele Buchman and Ron Cohen

Elizabeth

Dupuis

Doe, Moffitt, and the subject specialty

libraries

My laptop sticker says “Fight Dystopia” — a reminder to myself not to be too passive. After the last presidential election I learned to cope with a world that I found distressing and misguided by carefully rationing my intake of news and focusing mainly on the things over which I had control. Then in March the coronavirus came. We all sheltered in place for months — the scope of my world seemed even smaller, and the things over which I had control seemed even fewer. In the midst of this isolating and disorienting time, in May it felt like a bomb of collective awareness was tripped. Already shaken out of our normal routines, we are now struck by images and stories — yes, many stories — of the grievous, malicious, deadly acts against Black, Indigenous, and people of color and the rising chorus for change. Our American Spring amplified not only how differently people of color were experiencing the pandemic, but how differently their communities experience life in every way. To realize the just world I long for, so many parts of our systems and societies need to change to reflect equity, respect, and humanity. But in this moment, I am reminded that words and actions have great influence, that individual people can make a remarkable difference, that even small local actions can be powerful, and that we are all designers of the world we live in as well as the world we want to create. Fight dystopia!

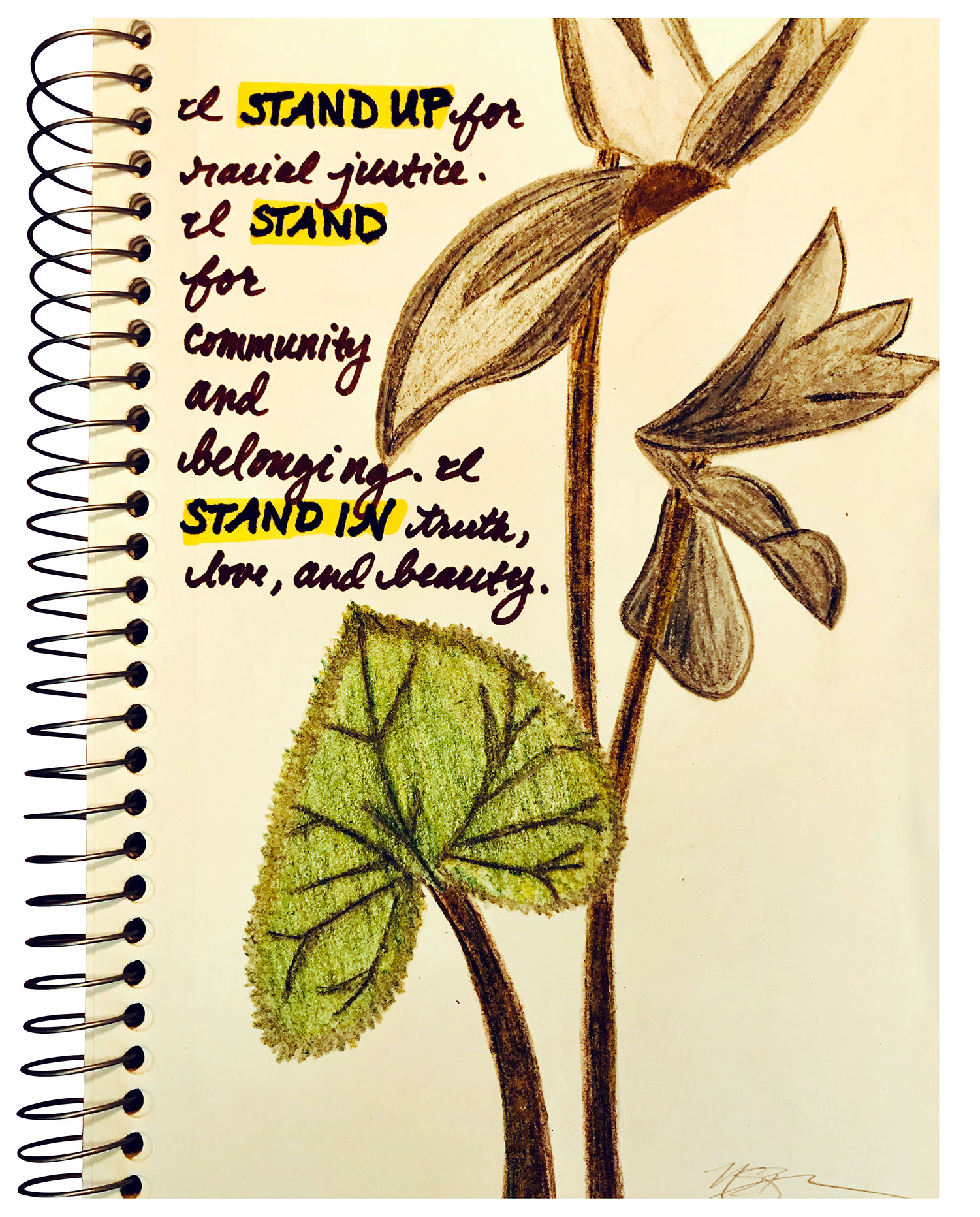

Nicole

Brown

Instruction Services Division

Erica

Howland

Social Sciences Division

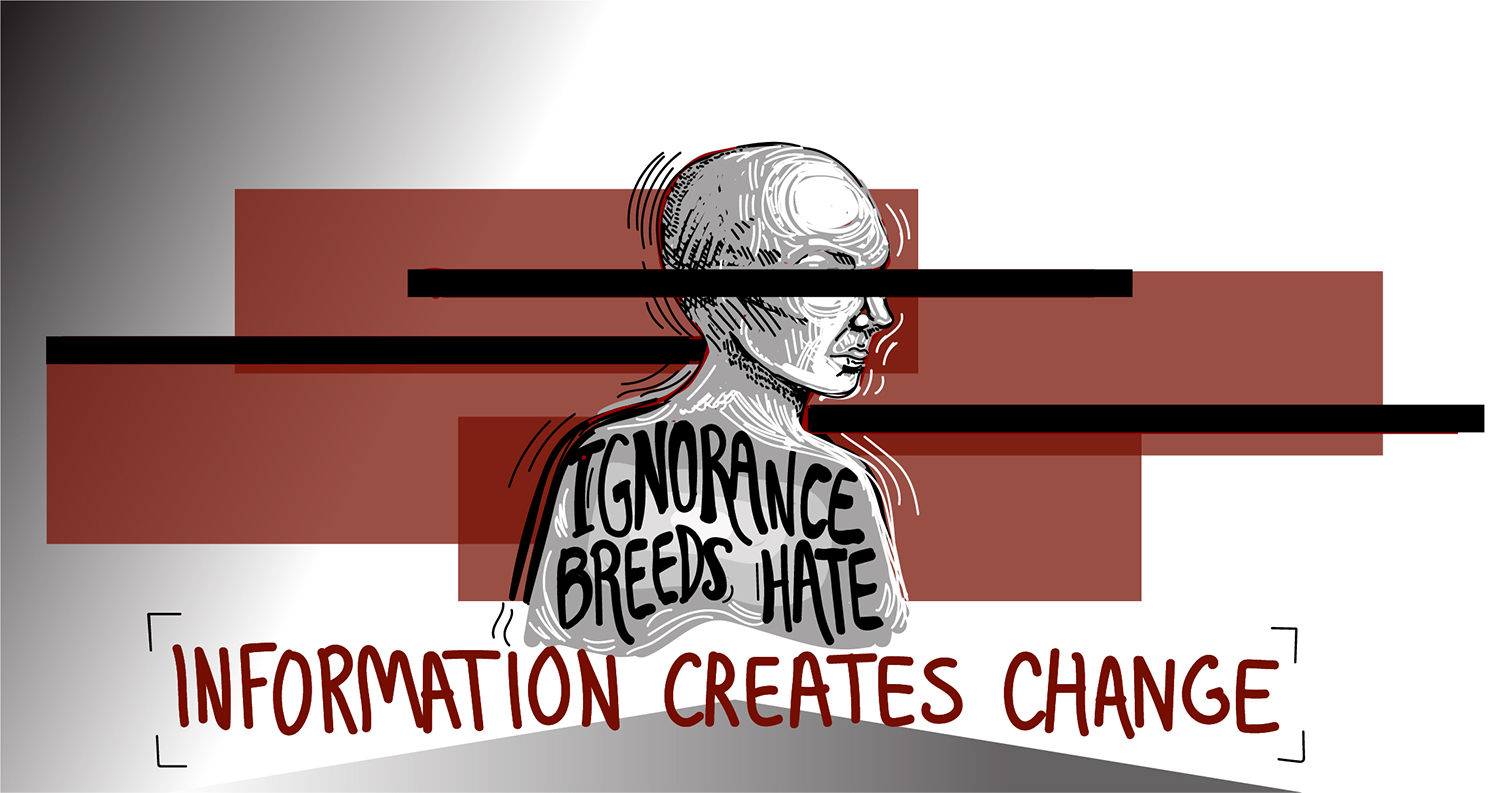

Ignorance Breeds Hate

Information Creates Change

David Eifler, pictured with his wife and son.

Photo courtesy of David Eifler

David

Eifler

Social Sciences Division

“White Privilege, Black Power”

The sign in my office reads, “If you don’t see white privilege, then you have it.” As the white father of a Black college athlete, I’ve had to face my white privilege — and its attendant racism — through my son’s young eyes. There was the time four kindergarteners, including my son, got into trouble for chasing another child in the schoolyard; the three white kids were scolded while my son was suspended for three days, and the father of the chased child demanded he be permanently expelled for being “dangerous.” At 8, he was forced to leave a Piedmont comic book store for reading the magazines, while other white kids continued to read and roam the store freely.

When confronted, the salesperson replied, “Sorry, I didn’t realize he was yours — he looks much older than 8.” My wife and I often reached for our blanket of white privilege to throw over these and other racist incidents. Yet our job was to raise a confident, independent Black man. We navigated the tension between helping him develop racial callouses while trying not to crush his spirit. One of “the talks” came at 16. Before teaching him to drive I had him rehearse how to display his hands when pulled over by the police; how to request permission to reach for his registration; how to “yes, sir” and “no, sir” a hostile white cop. He already knew, but I reminded him that “people who look like me are going to mess with people who look like you.”

At 18 he declined a scholarship to Cal because “Berkeley doesn’t show much love for football.” I understood the subtext: “Berkeley doesn’t show much love for Black football players.” His instincts may have been right; last year he had a run-in with the UCPD in University Hall when a random white person threatened to call the police as he entered the building. He calmly explained that he was helping his professor mom move into her new office — to no avail. When UCPD arrived, Mom drew on her arsenal of professorial privilege and unsuccessfully schooled the cop on racial profiling. No one left that encounter happy, but at least everyone left alive.

At 22, our son effectively manages his complex life as an adopted person from a multiracial family, finding support within his Black community of friends, birth family, coaches, and teammates. This community provides him the resilience and true power he needs to navigate the treacheries of being a Black man in America.

Reza

Yaghobi

Catalog & Metadata Services

We need a reform in our police department practices. I stand with my people who fight for justice, racism, and equality in a peaceful way. Our voices matter in this movement.

“

A

civilization

is

not

destroyed

by

wicked

people;

it

is

not

necessary

that

people

be

wicked

but

only

that

they

be

spineless.

”

— James Baldwin

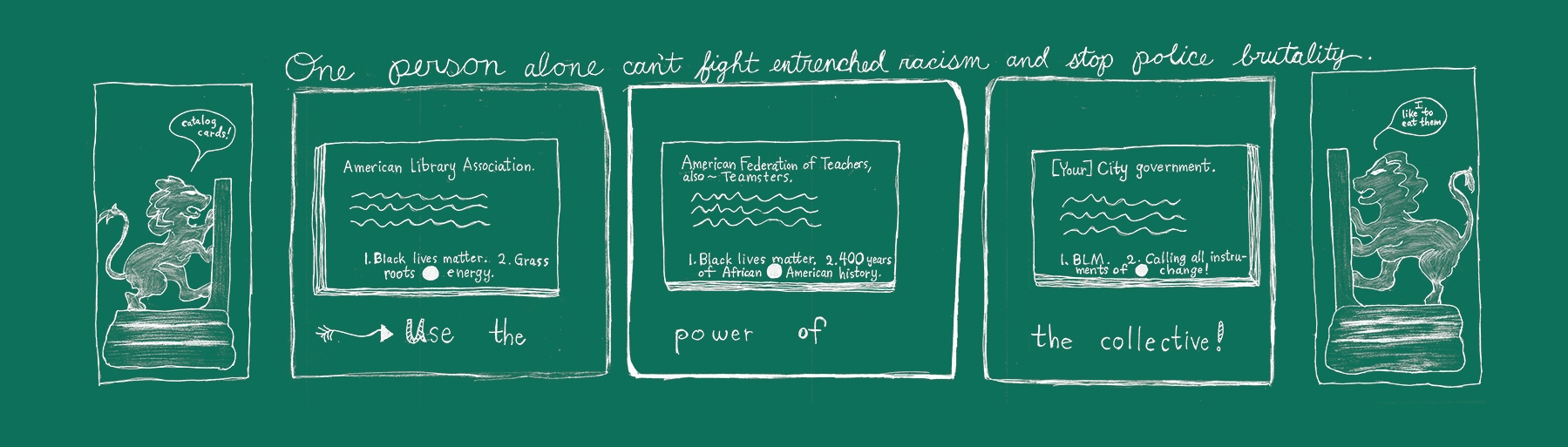

Illustration by Danielle N. Truppi

Jesse

Loesberg

Library Communications

In my first year of college, I took an introduction to political theory course whose core text was a collection of essays called Anatomy of Racism. Among its more provocative chapters was a piece about our country’s justice system. Because racism is our country’s default setting, the writer said, we should reverse our innocent-until-proven-guilty stance in cases involving an accusation of racial bias. In these instances, the default assumption should be guilt.

As a 17-year-old white student attending a mostly white private liberal arts college in the Northeast — and having graduated that spring from a high school that was more than 90 percent white, in a neighborhood that was 100 percent white — my reaction to this essay was exactly what you’d expect: anger, defensiveness, and a knee-jerk desire to defend what I perceived to be a bedrock principle of the American legal system.

That was over 30 years ago. I am ashamed to say that it really wasn’t until much, much later that I began to understand that my gut reaction in that first-year class was informed by white supremacy.

This isn’t to say that I passed these 30 years in a state of complete racial ignorance. I was a good performer of white liberalism: I took a lot more courses like that Political Theory 101 class; as a young man, I read The Autobiography of Malcolm X; I studied the work of Audre Lorde; I searched out histories of the Black Panther Party that weren’t written by white people; I could be counted on to say the right things at the right time. But all of these things were done in service of “understanding the Black experience.” I didn’t use them to recognize the white pipeline through which I was moving, and would continue to move, right up into my current position as the web designer for the UC Berkeley Library.

Ibram X. Kendi describes white supremacy as a continuous downpour that insists that you’re not actually getting wet. I’ve been holding a closed umbrella this whole time. It’s long past time for me to open it up, dry off, and see what I can do to make the rain stop.

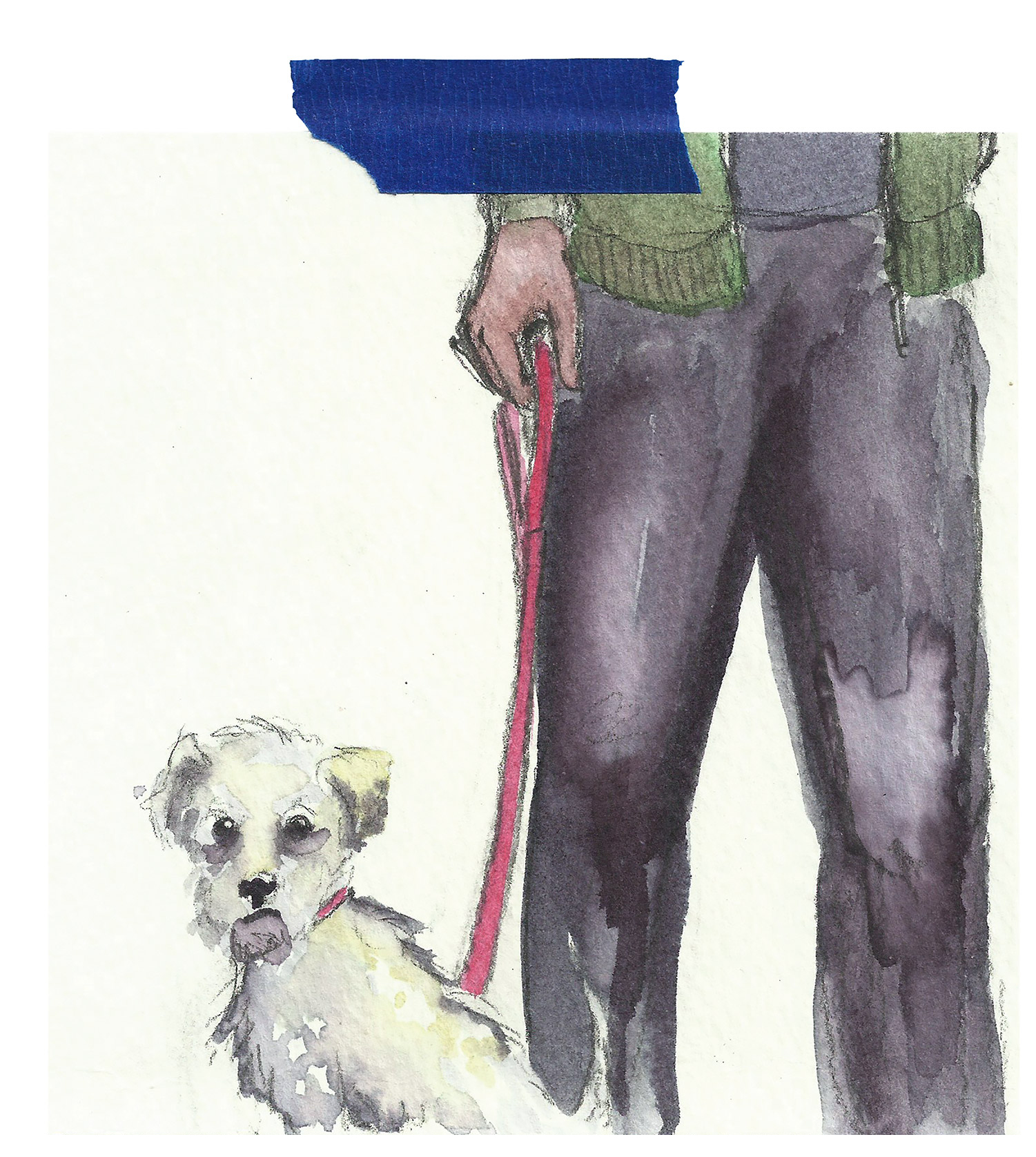

Danielle N.

Truppi

Library Business Services

Heading home with our signs from the vigil, a neighbor walking her dog stopped to ask us:

“Did you know the biggest percentage of people killed by police are white? It’s in the national database.”

She said it like a reprimand, like she was the only one with any sense. But I was holding a very long list of names of murdered Black people (many omitted, many unknown), and I knew she was trying to use numbers to tell the wrong story. Her story made everyone a fool, so there was nothing to do.

Illustration by Danielle N. Truppi

Lark

Ashford

The Bancroft Library

From an American Boomer, Old Caucasian Lady

Dear White People, Our lack of melanin and pigment genes DOES NOT make us superior to anyone! Stop embarrassing me.

Dear Black People, I apologize for my people.

“Child of the Universe”

You walk down the street, feeling all alone

with nowhere to call home

And the people who pass you by, turn their eyes

You are a Child of the Universe, born perfect and free

You have a right to be here, and

you are beautiful to me

Pain inside your heart, nothing left to give

Your love’s a fugitive

You have the strength to pull on through

You have to trust in You

Feel your power, hold your head up high

Shoot your dreams straight up into the sky

Rain washes away, the cobwebs in your mind

and you have survived

You’ll see the skies, will turn to blue

the light will shine through You

Know that You are a Child of the Universe, born perfect and free

You have a right to be here, and you are beautiful to me

— Lyrics by Lark Ashford

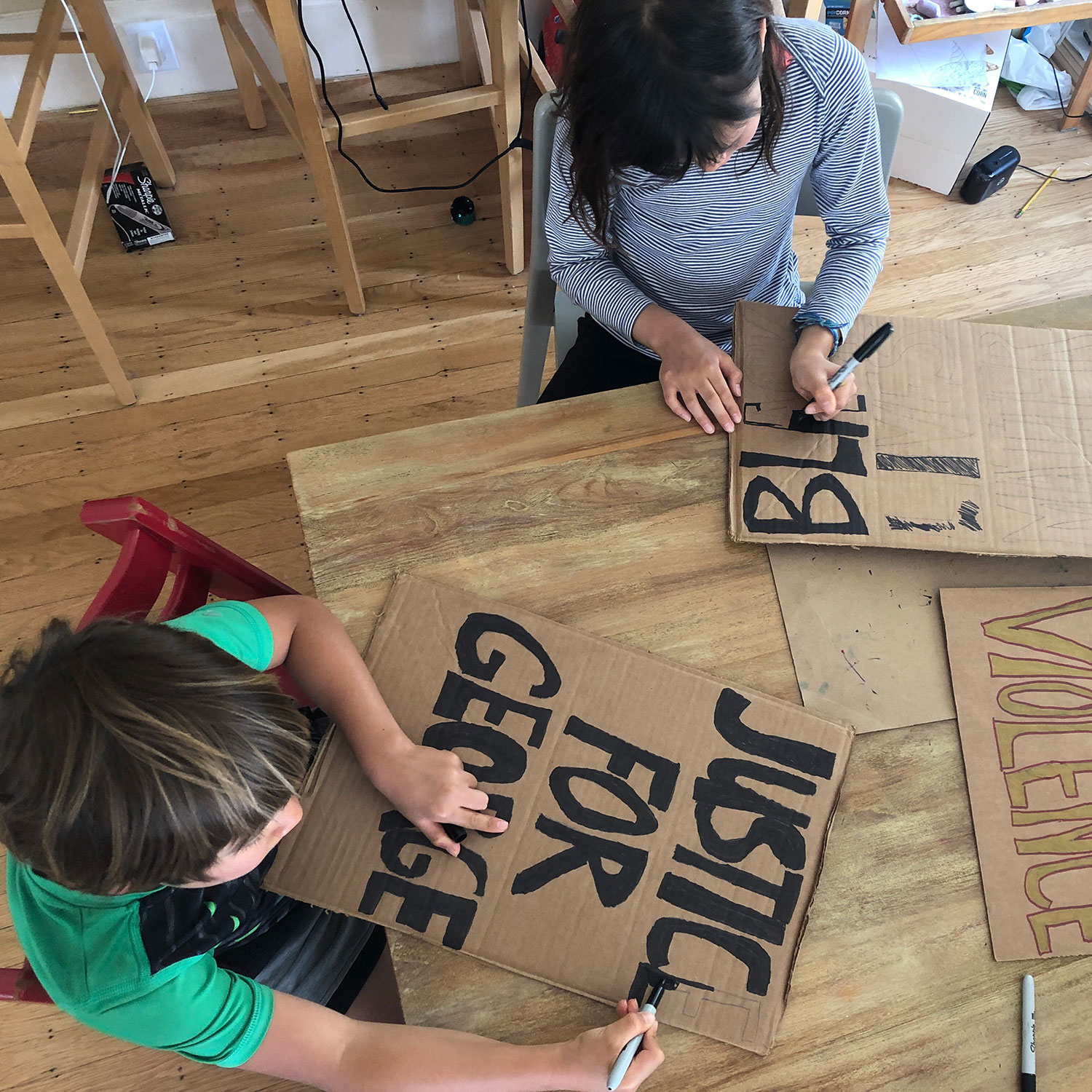

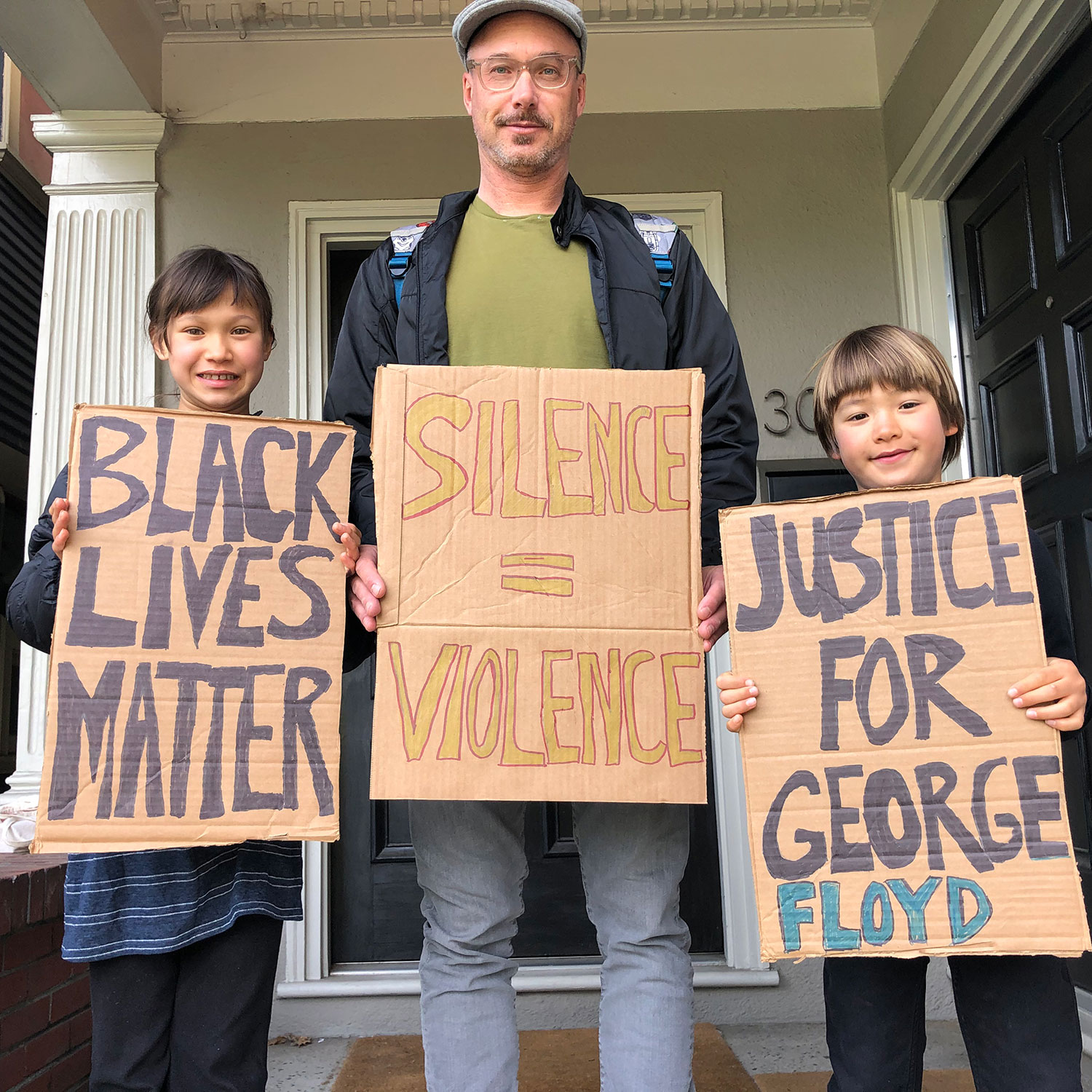

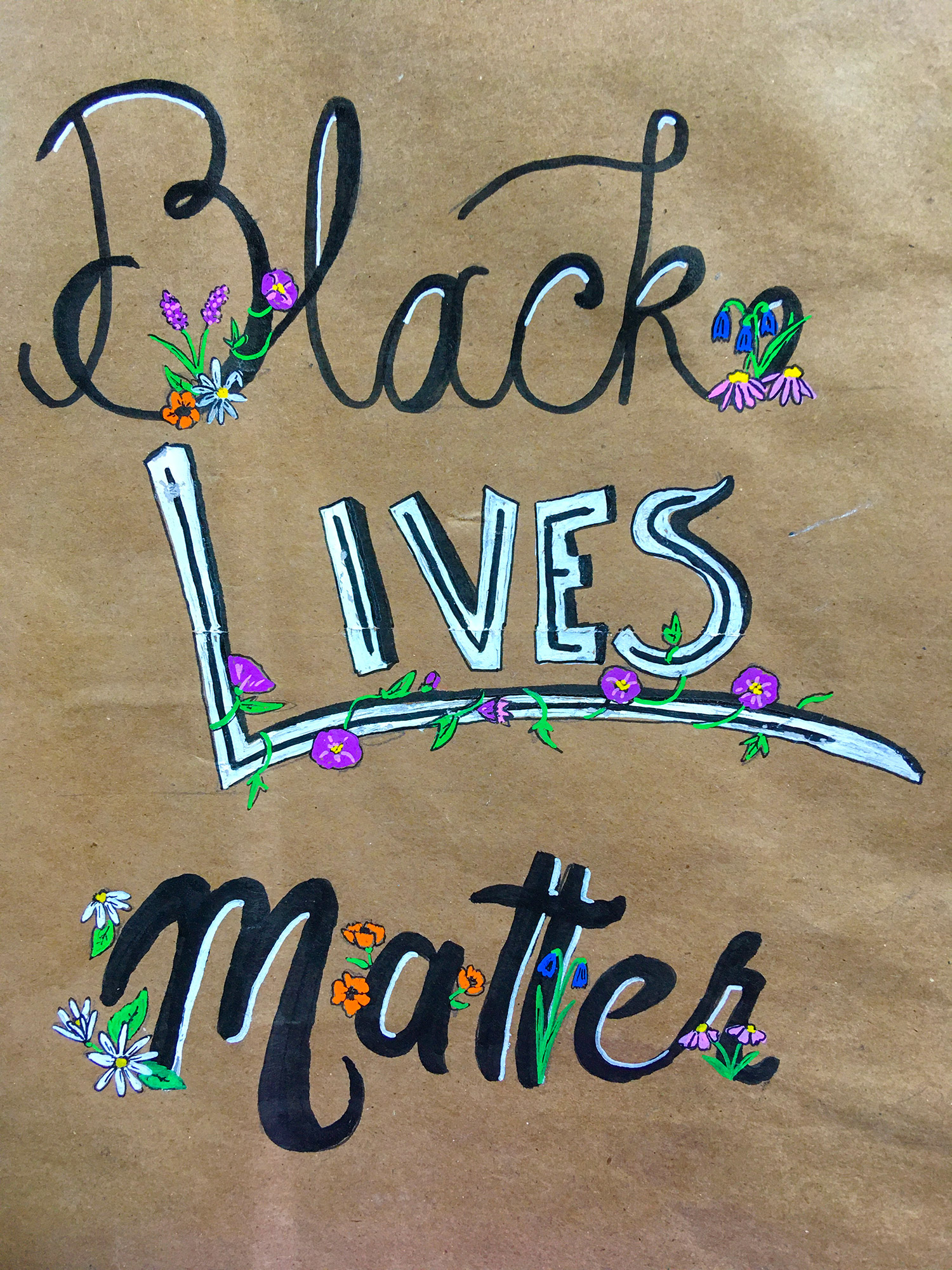

Becky

Miller

Life & Health Sciences Division

My son and I made this sign and joined other families in a low-key march. It was a small way we could be involved, and I was glad to do it together.

Photo courtesy of Becky Miller

Ryan

Barnette

Access Services Division

Crown

Claude

Potts

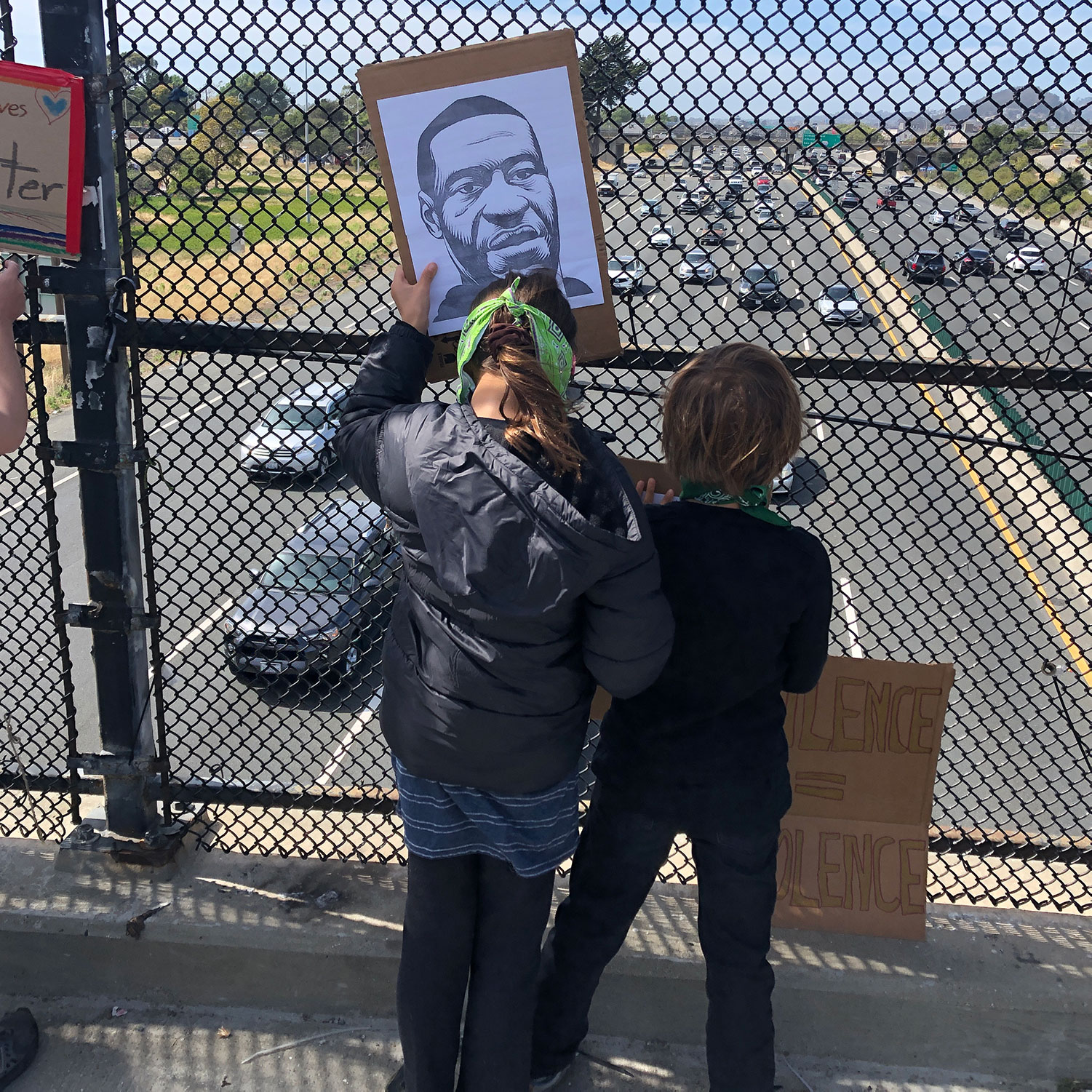

Arts & Humanities Division

Kids march for

Black Lives Matter

Berkeley

June 5, 2020

Photos courtesy of Claude Potts

A.

Hamilton

Library Communications

Handed an oversized pink heart, cut from construction paper, I was instructed to crumple it up into a ball, then pause, and uncrumple the paper and flatten it back into its original shape. Not having much available to manage this job, first I used a tissue box to try and iron out the creases, with minimal success, then decided to try other techniques — rubbing the paper along the edge of the table and then using the bottom of my fist to smooth out the larger creases on a flat surface. Nothing worked. The paper still had hundreds of wrinkles in it. In my head, I rationalized that if I had the right tools, I could steam and hot-iron the paper to flatten the creases but knew that the initial act of squeezing did more damage to the structure of the paper than what was visible to the eye. Along with other labels used to acknowledge racism as a form of social trauma are notions that resemble the outcome of my crumpled paper heart. Describing race as a social construct, or identifying institutional racism, implicit bias, and white privilege are heated topics in the news and among family, friends, and colleagues. In this environment, plotting a new course to make a difference in my community is frightening, but if I have learned anything at all from those who have lived before me, it is that understanding who I am and my truth is essential to preventing further hurt. I have to believe that standing up and building alliances will strengthen our abilities to empower change for Black Americans and people of color. We need to provide access to uncensored stories so that we can appreciate the struggles and contributions of communities who have been deleted or marginalized in history. By unveiling these truths, we’ll stop feeding into prejudice and begin to see pathways to equality through education. We may not see the power of this work in our lifetime, but we must continue for the benefit of future generations, and not give up hope.

Video by A. Hamilton

Annalise

Phillips

Instruction Services Division

Angela

Arnold

Arts & Humanities Division

“The Umbrella”

Ten years ago, after work early one rainy Friday evening, I stopped at my church just off campus to drop off sheet music (as a part-time professional soprano). Leaving there, it was sufficiently cold that I was wearing my down-filled black jacket. Rainy enough to use my (black) automatic umbrella a few steps out. A well-dressed woman and man, I imagine a couple, 60s or so, approached in the opposite direction on the sidewalk between the building and parking lot, perhaps headed to a public event scheduled there. I didn’t recognize them. The couple and I got ever closer.

I’d already begun raising my umbrella slightly (directed outward — I do not point umbrellas at people), then pressed its button to open it. Now a few feet in front of me, the woman gasped, jumped, and grabbed her companion. My umbrella opened as soon as she started. I instinctively smiled and said, “Hello.” I sensed a strange vibe, but I can try to please to a fault. We continued walking our respective ways. I soon heard her say to her companion, “I thought she ...”

A moment later, I couldn’t help thinking this woman imagined I had some kind of weapon and was drawing it. A painful inference. I am a brown person, and to me, the couple presented as white. Can opening automatic umbrellas startle people? I suppose so. But it was raining. The woman seemed to react not simply to the umbrella’s motion, but also to what she thought the situation, that motion from ME, was. I cannot help thinking there would have been no such scenario in her mind had I appeared to be white. I left what was to be a simple errand involving my church and beloved music very sad and upset.

Ann

Glusker

Social Sciences Division

Murals on Broadway

37° 47’ 58.272’’ N, 122° 16’ 27.228’’ W

Seventh Street and Broadway, Oakland

Photo by Ann Glusker

“

Ever since I first read it, an

Alice Walker title has pretty

much been my

life

motto.

And it has more power for me

now than it ever has.

The Way

Forward

Is with a

Broken

Heart.

”

“free people of color”

pre-1865

“citizens of color”

Martin Luther King Jr., 1963

“person of color”

(POC)

Frantz Fanon, late 20th century

“men of color”

(MOC)

“women of color”

(WOC)

“Black, Indigenous, and

people of color”

(BIPOC)

2010

Brian

Light

Social Sciences Division

“Being an Ally Is a Constant Thing”

Being a white man I have to think about it. I can walk through life and miss so many slights, and low-level attacks (microaggressions). I can ignore them if I do see them and pretend I didn’t. I can pretend, and few will ever call me out.

I try not to ignore them, though. I try to be intentional about what I say. I try to speak up when appropriate, and I try to listen. This is how I became an ally.

I will also say that to this day, I hate being in a room with only white people. Something about the homogenous grouping encourages the slights and dismissive comments about POC. I know this means those people always think those things, but in mixed company, they tend not to say them ... and frankly, that is one of the best arguments for political correctness ever. Thinking just a little bit before one speaks can make the world a more comfortable place for all of us.

Even being married to a Black woman and being the father of a Black girl does not mean I am an ally. I still need to actively think about them, and what they see, and listen to their concerns.

Perhaps the most important thing I need to do on a regular basis is listen.

Listen when I am told that something I said is offensive, listen to the struggles of others, and listen to suggestions on how I can help.

Jean

Dickinson

Catalog & Metadata Services

Marjorie

Bryer

and

Christina

Velazquez Fidler

The Bancroft Library

“Toward ‘an archive of the exorbitant,

a dream

book

for existing

otherwise’”1

We first want to acknowledge that we are on unceded Huichin Ohlone land, and that we stand in solidarity with striking graduate students at UC Santa Cruz. We say this because we know that the ongoing struggle we’re engaged in is not just for Black lives and liberation, but for the liberation of us all. Police brutality and disrespect for Black lives is not new. There’s a lot to say about the recent murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Tony McDade — among many others — but we can’t say anything that has not already been said by people of color for hundreds of years. We stand on the shoulders of folks who have stood up before us.2 As archivists we are fortunate to help preserve their history and culture.

Historically, archives have privileged white, male, heteronormative, middle- and upper-class, ableist, imperialist, and settler colonialist narratives. As archivists, we have an obligation and an opportunity to build stronger collections by addressing inequities in the archival record, and working to dismantle structural racism, anti-Blackness, and white supremacy in the archives. As advocates for social justice, we have a duty to amplify voices that have been excluded or marginalized, not just to tell more inclusive histories, but to correct the historical narrative.

As archivists we will listen to and share resources with community archives and underrepresented groups so they can preserve their own histories on their own terms. In our experience, when people see themselves in the archival record, they make emotional and political connections with their past, recognize intersectionality and common cause with other oppressed groups, and are inspired to envision a more hopeful future.

We cannot understand our institutions without understanding structural racism. Reni Eddo-Lodge provides a stark definition: “Structural racism is dozens, or hundreds, or thousands of people with the same biases joining together to make up an organisation, and acting accordingly. Structural racism is an impenetrable white workspace culture set by those people, where anyone who falls outside of the culture must conform or face failure.”3

We recognize that, like inherited wealth, there is inherited power at all levels of academia. The concept of “the right fit” is an insidious form of structural racism, preserving a disproportionately white academic culture.4 Black faculty members number just 3 percent at UC Berkeley.5 The repercussions of this truth reverberate across all aspects of our campus. We recognize how this permeates our own library spaces.

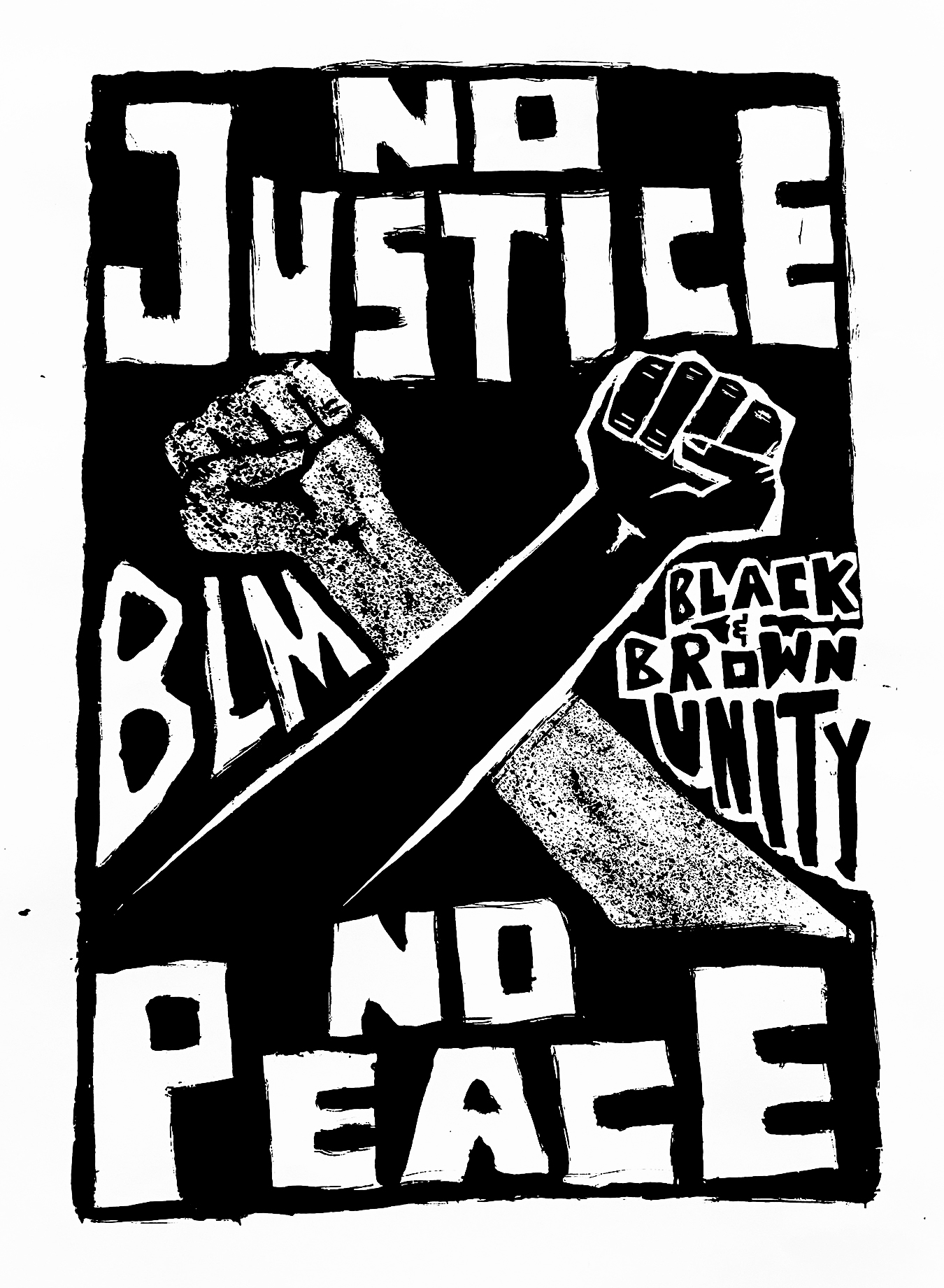

Youth Solidarity Project poster from a Richmond protest on June 8, 2020.

We have to do better. It is our responsibility as a community to continue to identify where and how current practices continue to support structural racism. It’s also our responsibility to then strategically and thoughtfully rectify these long-standing problems, and to be led by the chorus of voices that have brought us to this long-overdue moment.

One great thing about working at Berkeley has been collaborating with colleagues in support of the struggle for racial justice and collective freedom.6 For Christina, this includes serving as co-chair on the LAUC-B Diversity Committee. For Marjorie, this includes working on exhibits that document solidarity among marginalized groups. We look forward to doing more in service of these struggles.

Our identities as Latina and queer, respectively, do not elevate our understanding of the Black experience, but we recognize that we are stronger united. This call to stand up and say something unites us in our advocacy and our shared responsibility as colleagues to actively work toward a transformed archival framework and a society that privileges living-wage jobs and affordable housing and health care over policing, prisons, and profit.

We hope that, collectively, the contributions to this publication send a larger message of love for our diverse community, but also express our grief and anger for the injustices that remain.

1 Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York, 2019), p. xv.

2 We’d like to recommend this webinar from the UC Humanities Research Institute: “The Fire This Time: Race at Boiling Point”, featuring Angela Y. Davis, Herman Gray, Gaye Theresa Johnson, Robin D.G. Kelley, and Josh Kun.

3 Eddo-Lodge, Reni. (2018). Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race.

4 Sensoy, Özlem and DiAngelo, Robin (December 01, 2017). “‘We Are All for Diversity, but . . .’: How Faculty Hiring Committees Reproduce Whiteness and Practical Suggestions for How They Can Change.” Harvard Educational Review, 87, 4, 557-580.

5 “Workforce diversity.” (2020, May 21).

6 Thanks to our colleagues at ESL for their powerful statement, “The Ethnic Studies Library Statement of Solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives” (2020, June 12). Retrieved from http://eslibrary.berkeley.edu/.

Murals on Broadway

37° 48’ 39.096’’ N, 122° 16’ 1.308’’ W

22nd Street and Broadway, Oakland

Photo by A. Hamilton

Contributors

Angela Arnold

Lark Ashford

Ryan Barnette

Nicole Brown

Marjorie Bryer

Michele Buchman

Jean Dickinson

Elizabeth Dupuis

David Eifler

Christina Velazquez Fidler

Ann Glusker

A. Hamilton

Erica Howland

Brian Light

Jesse Loesberg

Becky Miller

Shannon L. Monroe

Annalise Phillips

Claude Potts

Danielle N. Truppi

Reza Yaghobi

Stand Up and Say Something

Project Team

A. Hamilton

Tiffany Grandstaff

Tor Haugan

Virgie Hoban

Amber Lawrence

Jesse Loesberg

Jami Smith

Alison Wannamaker