How can the Library apply a sharper social justice lens to its everyday work? Last November, staff members in the Library’s Access Services Division created a social justice reading group — a space for staff members to select, read, and discuss articles and books that explore how Library services, facilities, and collections may be affected by implicit bias. The group discusses the barriers to entry faced by underrepresented groups — and how the Library can effect change.

One hundred and fifty years ago, women were first admitted to UC Berkeley. But curricula that treated women equally were still far off. In the 1970s, angered by an absurdly male literary canon, a group of women in the campus’s comparative literature program fought for the ability to study women in history and society, ultimately establishing the university’s Women’s Studies Program in 1976. “I don’t think any of us were conscious of starting a movement,” recalls Gloria Bowles Ph.D. ’76, founding coordinator of the program. “We were just responding to an outrage, which was that we were students of comparative literature — we all studied four foreign languages — yet we read very few women.” Now, a growing collection at The Bancroft Library reveals the long, and at times turbulent, journey behind the women’s studies movement, with heated letters, program proposals, course syllabi, feminist pamphlets and ephemera, and more.

In our quest for common understanding, it helps to start with the source:

the voices, writings, and portraits of the people and communities around us. This past spring, the Library launched its

Digital Collections website, where thousands of these human stories live on. With photographs, videos, documents, audio, maps, and more, the platform is home to more than 100,000 gems, from video interviews with women in the Black Panther Party to the archives of

The Daily Californian, Berkeley’s independent student newspaper. And the materials are freely available to all. “At the heart of this is freeing up our treasures from the boxes that they sit in — moving them from boxes to bytes, from shelves to screens — so they’re available to researchers around the world,” says Salwa Ismail, associate university librarian for digital initiatives and information technology. At the same time, the Library published a unique

community engagement policy that will guide staff members as they consider requests from the public to remove from the site culturally sensitive materials, or items that may raise an ethical, legal, or safety concern for the community.

This past spring, a team of undergraduates in the student club Invention Corps helped the Library

brainstorm new designs for Moffitt Library’s Makerspace, a tech-filled hub for innovation and creation. During the pandemic, the students continued undeterred, sharing not only ideas for the space, but also positivity and hope. “It’s been super helpful to have a cohort of students who are really engaged and invested in these projects,” says Annalise Phillips, the Library’s maker education service lead.

With every challenge comes an

opportunity to grow. And the behemoth we faced this year proved no different. As buildings closed and classes went online, the Library bolstered its support for remote learning and research. The Library began a concerted effort to provide free digital versions of course readings, easing a financial burden for students facing mounting challenges. Research consultations and instruction sessions for classes became exclusively virtual. The launch of the

Digital Collections website — plus the Library’s ongoing digitization work — allowed researchers from around the world to sift through the Library’s one-of-a- kind treasures from anywhere. This pivot would not have been possible without the sturdy foundation the Library had built for teaching, learning, and researching in a rapidly shifting information landscape. “The Library’s thoughtful choices and wise investments over the past decades helped us tremendously,” says Elizabeth Dupuis, senior associate university librarian and director of Doe, Moffitt, and the subject specialty libraries.

With the world gripped by the COVID-19 pandemic, the C. V. Starr East Asian Library sprung into action, collecting information and materials from China that cast light on the scientific realities of the virus and the lived experiences of those affected by it. With the threat of government censorship looming, library staff members swiftly captured history as it was unfolding, preserving materials such as government documents, information about the outbreak’s origins, literary works about life amid the pandemic, and social media posts chronicling the crisis. The collection will afford future researchers the opportunity to look at these strange and difficult times as they actually were, with depth and clarity. “We feel that if we do not do this, a lot of valuable information will be lost permanently,” says Peter Zhou, director of the East Asian Library. “We hope that this special collection will be of tremendous value to scholars and the general public as documentation of this unprecedented experience in our lifetimes.”

As a freshman, Erinn Wong ’21 penned a paper called “Digital Blackface: How 21st Century Internet Language Reinforces Racism.” Wong contends that people who aren’t Black but lean on expressions and portrayals of Black people to communicate and convey their emotions on the internet (in the form of GIFs, TikToks, memes, and more) co-opt elements of Black culture while, intentionally or not,

perpetuating harmful stereotypes. For her efforts, Wong earned a Library Prize honorable mention. “While I am happy the Library Prize recognizes student work, I am most happy to know it motivates, sparks, and ignites student interest in exploring the university’s extensive research resources,” says Charlene Conrad Liebau ’60, a Rosston Society member of the Library Board, whose endowment makes the Library Prize possible.

Last year, negotiations stalled between the University of California and Elsevier, the world’s largest scientific publisher —

a high-profile development in UC’s ongoing quest to transform the scholarly publishing industry. Since then, UC has redoubled its commitment to usher in a world where academic research is freely available to everyone, inking transformative open access deals with a handful of publishers,

including Springer Nature, the second-largest academic publisher in the world. All the while, without direct access to Elsevier materials, members of Berkeley’s community could still get their hands on the publishing giant’s articles with the

reliable support and expertise of the Library’s borrowing and lending unit, Interlibrary Services.

Say you’re a student at UCLA, and you need a book from the UC Berkeley Library. To get your hands on it, you’d have to hunt it down and request it on the UC libraries’ shared discovery platform — a less- than-seamless experience. But that won’t be the case for much longer. A visionary systemwide project will not only unify Berkeley’s vast collections (physical and digital), it also will bring together the collections of libraries across the 10-campus University of California system under one virtual roof. This year saw the selection of a vendor, software company Ex Libris. And next summer, the new system is slated to go live. “This is a truly transformative and innovative project that will help us enhance how we serve our community,” says Salwa Ismail, associate university librarian for digital initiatives and information technology.

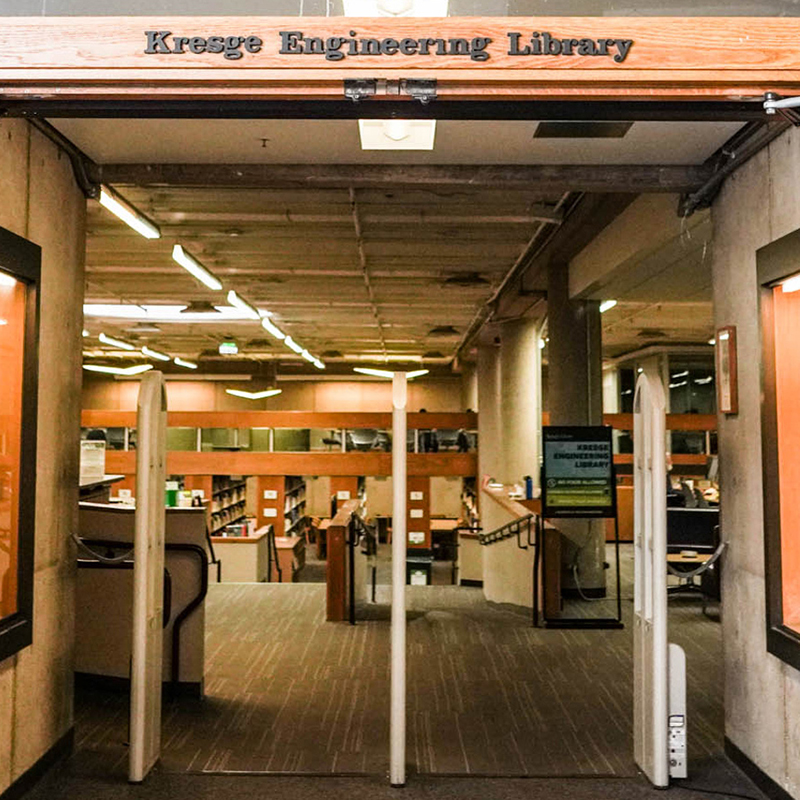

UC Berkeley’s Kresge Engineering Library is taking a stand against the status quo with its

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Collection — a growing set of materials that shed light on the hurdles underrepresented groups face in STEM and concrete ways educators can help close the gaps. A collaboration between the Engineering Library and the College of Engineering, the collection aims to make the world of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) on campus and beyond a more inclusive, enlightened space. “We’ve been heartened to see that usage of the collection has included the College of Engineering as well as faculty and students across the entire campus,” Engineering Librarian Lisa Ngo says. “Our hope is that the collection ... spurs action.”

For the uninitiated, the U.S. census might seem like a topic that’s drier than the Mojave Desert, piquing the interest of a small handful of dataphiles. But that notion was torn asunder by an incisive exhibit filling Doe Library’s Brown Gallery, in time for the 2020 count.

Power and the People: The U.S. Census and Who Counts offered an inside look at the decennial drive for data over its 230-year history. The exhibit was complemented by a kickoff event, spotlighting how students have woven census data into their projects. “I love (the census) so much because most of history is about wealthy people and powerful people, and you have to fight so hard to find these little records — these little traces, these ghosts — of the regular people,” says Susan Edwards, social welfare librarian and head of the Library’s Social Sciences Division. “But the census has it.”

In 2017, Charles Reichmann,

a lecturer at Berkeley’s law school and an attorney, made an

unexpected discovery in the throes of his research at The Bancroft Library: a speech revealing racist, anti-Chinese views of John Henry Boalt, the historical namesake of the UC Berkeley School of Law’s Boalt Hall. That discovery sent Reichmann on a monthslong exploration of Boalt’s legacy, which included penning an

op-ed and a law review article that raised questions about honoring the past while staying true to our better angels. The path led, ultimately, to campus officials stripping Boalt’s name from the building, announced in January by Chancellor Carol Christ. “I spent a few months doing research and writing because I wanted to broadcast the history,” Reichmann says. “I wanted to let people know what had really happened.”

As part of its ongoing effort to make its resources available to all, the UC Berkeley Library launched a

new scanning service to transform print materials into digital formats more accessible to the campus’s diverse scholarly community. The service expands upon one the Library began in 2012, which helps students registered with the campus’s Disabled Students’ Program attain digital versions of Library materials. Now, faculty members, instructors, and visiting scholars with print disabilities can get digital versions of Library materials, too. “Access to knowledge is our core mission, pure and simple — you could boil everything we do down to that,” says Susan Schweik, an English professor who studies disability in literature. “As a public university, we should be serving the real public, ... and the public that actually exists learns in a variety of ways.”

Imagine working hard for years — overcoming constant obstacles — to finally get accepted into UC Berkeley, but never really feeling at home. That was one of many challenges shared by a

panel of formerly incarcerated students at an event at Moffitt Library’s Free Speech Movement Café in February. After a screening of the film

From Incarceration to Education, a panel of students from the Berkeley Underground Scholars program opened up about their experiences in college, discussing some of the challenges, stereotypes, and probing questions they’ve been forced to confront. (“What were you doing during that World Series?” might sound innocent, but the answer — “I was watching it from my cell” — might be more than a student wishes to share, explained scholar Daniela Medina.) At once inspiring, poignant, and eye-opening, the discussion addressed the challenges of reversing the school-to-prison pipeline and provided accounts from students who have made that leap — and who are working to make it easier for others to do the same.

An 8-foot mummified crocodile. A 4,000-year-old statue from the Great Pyramids of Giza.

Papyrus fragments from a lost play by Sophocles. Side by side, these ancient texts and delicate artifacts cast color and context upon one another, offering modern viewers a peek into life in antiquity. For the first time, objects from Berkeley’s Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology were united with ancient texts from The Bancroft Library’s Center for the Tebtunis Papyri in an

expansive exhibit at the library. Called

Object Lessons, the exhibit provided a window into the everyday lives of Egyptians and revealed how these treasures landed at UC Berkeley. “For me, the draw of the exhibit is the ability to be an educator,” says Andrew Hogan, a lead curator of the exhibit and postdoctoral fellow at the center. “This is an amazing research post, but it allows us to feed our soul on the other side, to think about: How is a sixth-grader going to take this? How is a Cal undergrad going to approach this?”

In an era rife with political division, how do we find common ground beneath the surface? That subject was on the menu at this year’s

Luncheon in the Library. At the talk — part book club, part therapy session — sociology professor and author Arlie Hochschild shared insights from her 2016 bestseller,

Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, which draws on Hochschild’s interviews with tea party conservatives in the American South. Chatting over the meal that followed, Linda Tran ’07, M.A. ’10 said the author’s work provides a model for building empathy. “The conversations she’s been having in the South will help with the conversations that we have at home,” Tran said.

“The humanities are the antidote to our very divided society,” says Library supporter and local exhibit curator Alan Templeton. “The humanities force you to have empathy for other points of view.” A lifelong library lover and museum aficionado, Templeton recently gifted the Art History/Classics Library an endowment of $250,000 that will support Berkeley’s fine arts collections, focusing on European art history, for decades to come. The fund is a boon for the faculty members and graduate students who rely on the Art History/Classics Library, says Art Librarian Lynn Cunningham, as well as for the global community of scholars who visit the library for its preeminent resources. For Templeton, the gift is both a tribute to the library’s help in the past and an investment in its power into the future. “Art is one of the best ways to bring the past back to life and to help people become part of a larger world,” he says.

The 87-million-year-old Triceratops fossil at the entrance to the Bioscience, Natural Resources & Public Health Library holds a clue: Treasure lives here. At an event honoring the Library Legacy Circle of The Benjamin Ide Wheeler Society, guests got a close-up look at some of the library’s

most unusual and beautiful items. Following brunch, supporters gathered for a special presentation and tour of the library, whose collections cover everything from botany to toxicology, zoology to environmental health. Rare items on display included an original letter from naturalist Charles Darwin and an official White House cookbook, first published in 1887. The event — an annual cornucopia of rare materials set in a different library each year — honors members of the Legacy Circle, a group of supporters who have remembered the UC Berkeley Library in their bequest plans.

This year, the C. V. Starr East Asian Library held an

event celebrating the remarkable legacy of the Rev. Yehan Numata, who believed that the spread of Buddhism would help bring peace to the world. The event doubled as a reception for an exhibit featuring some of the library’s most precious materials related to Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Buddhism. On display were stunning prints of Buddhist temples and maps of pilgrimage routes; popular texts and treatises from Buddhist scholars; an excerpt of a 600-volume accordion-fold sutra; and more. “Berkeley has been collecting materials in the field of East Asian Buddhism for close to 100 years,” said Peter Zhou, director of the East Asian Library. And the exhibit, he noted, shows how that collection has grown. After presentations from Numata’s grandson and university officials, koto player Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto filled the first floor of the library with music.

It was a sight to behold: a

stunningly detailed replica of the UC Berkeley campus (including its libraries) in the massively popular video game

Minecraft. Created during the pandemic by a team comprising mostly Cal students, Blockeley University served as the virtual venue for an unofficial 2020 graduation ceremony. This year, staff members at The Bancroft Library began an effort to document this glimmer of light in a time of hardship. Plans include collecting a

Minecraft version of the project, the official project website, written reflections from Blockeley University builders, and a team pin and sticker. Instrumental to the effort is the work of Christina Velazquez Fidler, brought on this year as Bancroft’s first full-time digital archivist — an essential force as the library acquires new types of collections. “The project in itself reflects the ingenuity of UC Berkeley students, but it also fits more broadly into the documentation of the campus community’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Kathryn Neal, associate university archivist at Bancroft.