In so many ways, this was a year we’d just as soon forget. But at the UC Berkeley Library, forgetting isn’t in our nature.

When COVID-19 entered our lives, we were met with a cascade of emotions and disruptions unlike anything we’d experienced. But, true to our mission, we seized the opportunity to learn and grow. We asked ourselves: How can we build a library that’s better, stronger, and more resilient than before?

The answer to that question takes many forms, from the opportunities born from disruption to the services fine-tuned for a new reality.

The Library has an impossibly long memory. And for good reason: Not only do we serve the needs of today — with foresight, we gather information that will empower scholars, students, and problem-solvers many generations into the future.

So, yes, it might be tempting to forget. But we know the power of remembering.

Everything is connected

Reserved for everyone

Mysteries solved

Treasures shine online

As the summer approached, a revolution was just around the corner. The Library was in its final push for the launch of a powerful new platform, the culmination of a massive effort spanning the entire University of California system. As one of the largest public university systems in the world, UC holds a vast collection of resources in its libraries. However, until recently, each campus library had its own catalog, making it hard for patrons to find what they needed if it was held at another campus. UC Library Search, launched in late July, changed all that. The platform unifies Berkeley’s vast collections (physical and digital) and brings the collections of libraries across UC’s 10 campuses together into the same system. It’s a game-changer for students, scholars, and researchers, who now have a one-stop shop for finding and borrowing resources from libraries not just at Berkeley, but across the UC system.

When the pandemic hit, the Library needed to adapt to meet students where they were — that is, everywhere. A new electronic reserves program was born of that need. The fully digitized version of course reserves gave students across the globe seamless access to articles, books, and videos for their classes at no cost. The program provided much-needed financial relief for students amid surging textbook costs, with Berkeley undergraduates estimated to spend $1,118 on books and supplies in the 2021-22 academic year. “These are historic times, where everything has shifted for our students,” says Salwa Ismail, who oversees the e-reserves program as the Library’s associate university librarian for digital initiatives and information technology. “We wanted to ensure that required readings for their classes were one thing they didn’t have to worry about.” In line with its public mission, the Library has also shared its digitized volumes with libraries worldwide.

Have you ever found an old photo in the house and, despite the handwritten note on the back, thought: What is this? That happens at libraries too. During the pandemic, employees in The Bancroft Library’s pictorial unit conducted detective work on obscure historical images, tracking down new details to enhance their searchable descriptions, so the photos are easier to find online.

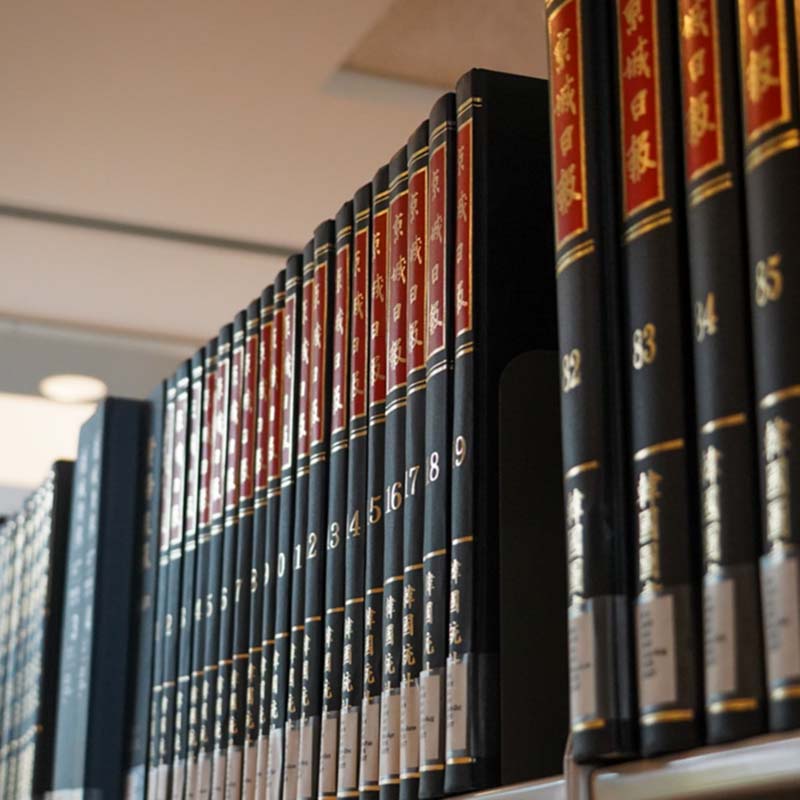

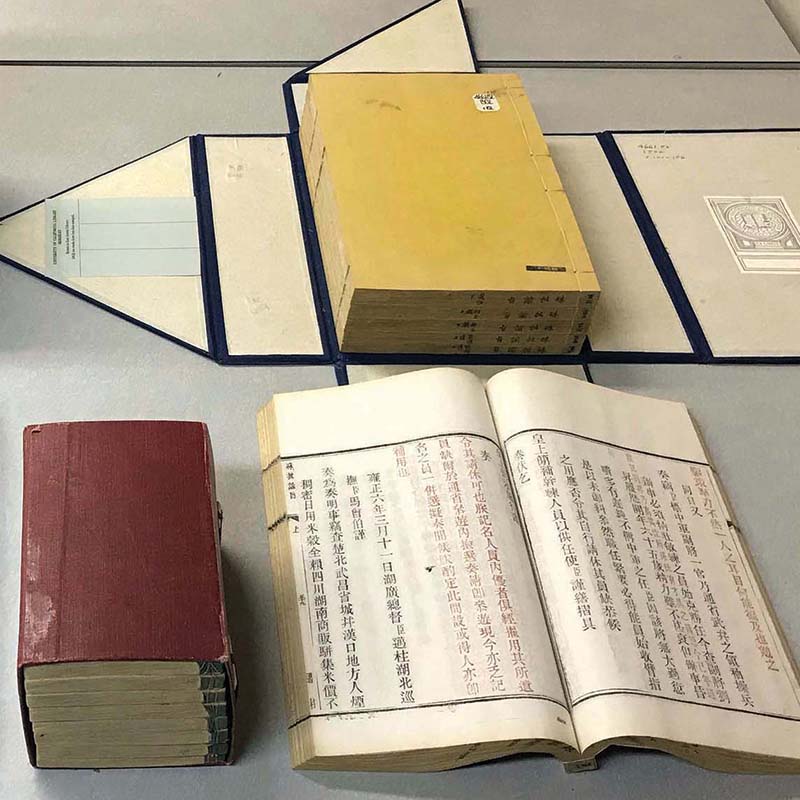

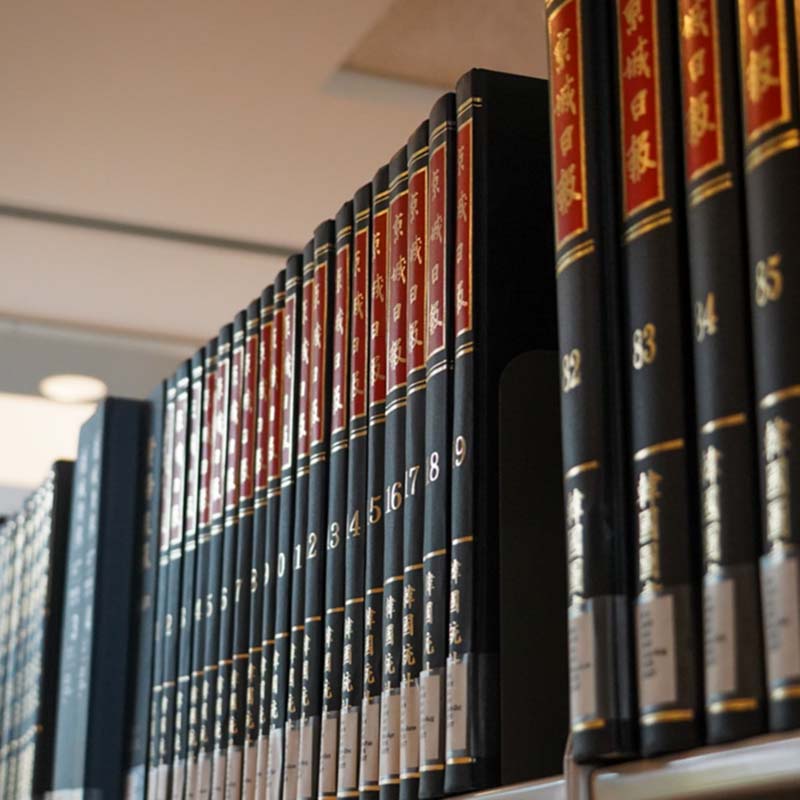

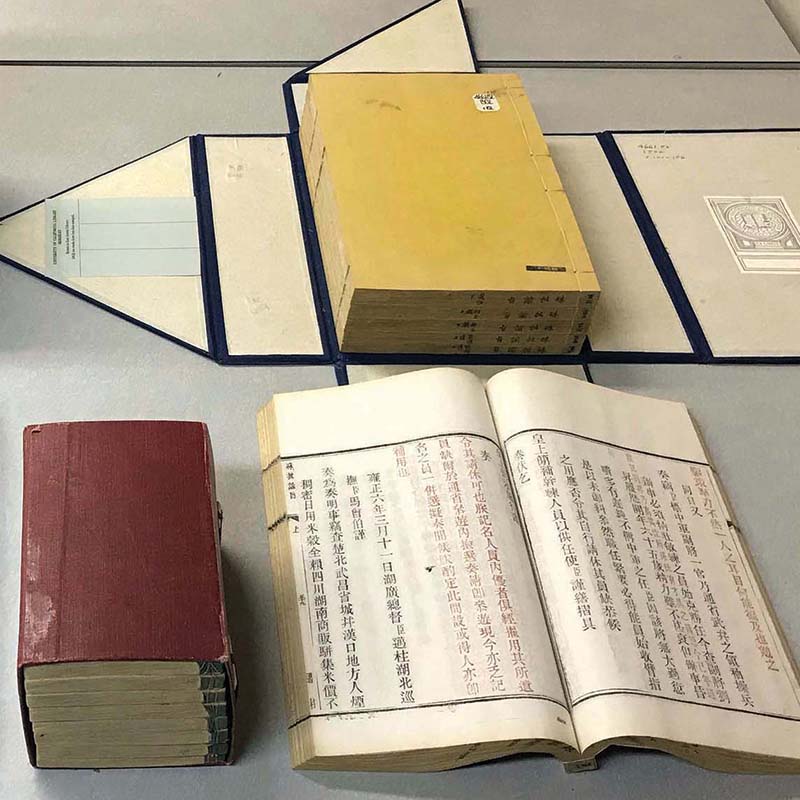

One silver lining that appeared as the pandemic pushed into year two: a groundbreaking

new partnership with Sichuan University that will enable the digitization of most of

the pre-1912 Chinese language materials in the C. V. Starr East Asian Library’s

collections. The initiative, supported by funding from the Alibaba Foundation, will

bring these extraordinary items to life in vivid detail for researchers today and for

generations to come. “These are priceless materials,” says Peter Zhou, director of the

library. “Some of them are the only pieces of that publication in the world.” Among the

treasures — which include rare woodblock editions and manuscripts — are volumes printed

from blocks engraved during the Song and Yuan dynasties. Through machine learning,

ancient Chinese characters are converted into machine-readable text, allowing for granular searches and greater accessibility. And all of these treasures will be available 24/7, to anyone, anywhere, through

the Library’s Digital Collections portal.

A new frontier

Words matter

Solutions by students

Knowledge to go

Nothing quite compares to the West. And now, The Bancroft Library is able to shine a brighter light on the region, thanks to the success of its Bancroft & the West campaign. Bancroft’s Western Americana materials, which comprise the library’s largest collection, document the vast region stretching from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, and from Alaska to Panama. Funds raised through the Bancroft & the West campaign help the library build this vital collection and connect materials with the communities they represent. The initiative, which publicly launched in spring 2018, has provided financial support for the preservation of Bancroft’s Western Jewish Americana archives; the acquisition and cataloging of artifacts that deepen our knowledge of California; the collecting of stories of women leaders at Berkeley; and many areas in between.

In recent years, momentum had been mounting to remove the controversial term “illegal aliens” from the Library of Congress’ standardized subject headings list. While an earlier effort was thwarted by conservative lawmakers, the UC Berkeley Library last year took a simple but significant step in support of inclusivity by layering the term “undocumented immigrants” into its 5,000-plus related records.

Last year, as cracks from the pandemic spidered into every aspect of life, the

Undergraduate Library Fellowship program went remote. The fellows proved

resilient, but something was missing. So starting in fall 2020, the program

shifted from having students work on their own projects to collaborating on

bigger efforts to help solve some of the Library’s most pressing challenges.

One team of fellows, for example, focused on outreach, with an emphasis

on diversity, equity, and inclusion. The team surveyed staff members about

resources to share with underrepresented populations, and developed an

easy-to-navigate database of multicultural materials. The peer-to-peer learning

program’s shift of direction nurtured true fellowship and reflected the user-centered

approach of the Center for Connected Learning, the innovative

new vision for a renovated Moffitt Library. “It’s just so wonderful seeing our

fellows grow as individuals,” says Kristina Bush, UC Berkeley’s digital literacies

librarian, who co-runs the fellowship program. “They’re all go-getters and

resilient. They’re going to rule the world someday.”

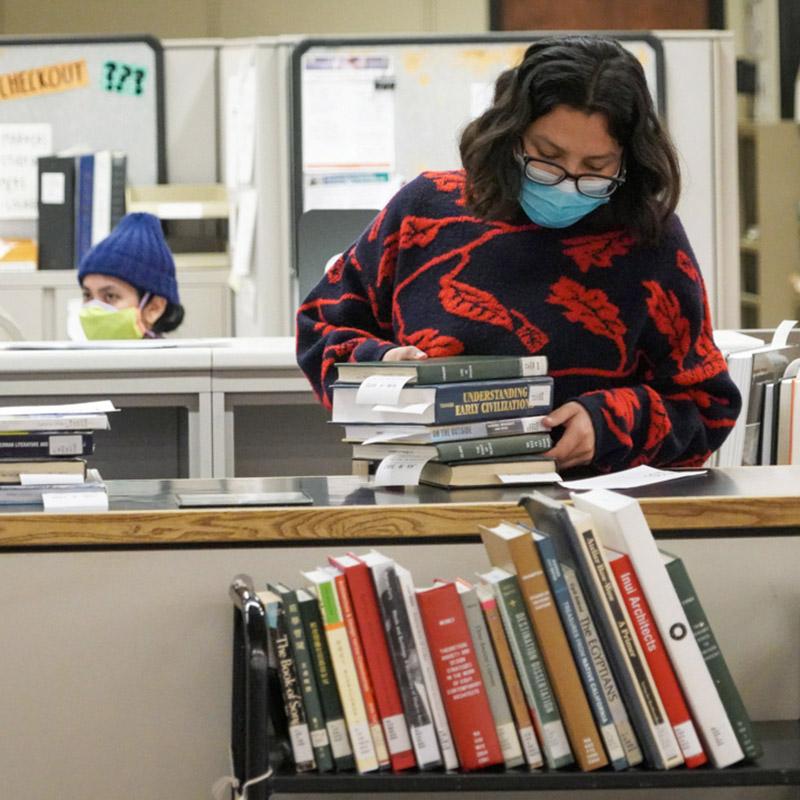

With the libraries suddenly closed, the UC

Berkeley community was cut off from one of its

most cherished resources: its physical collections,

the massive stockpile of information that fuels the

research and learning on campus, and far beyond. But

the Library couldn’t let that happen for long. During

the first fall semester of the pandemic, Oski Xpress,

a new contactless pickup service, was born. Through

the service — the first of its kind for the Library —

members of the Berkeley community could safely get

their hands on materials they otherwise wouldn’t be

able to access. After finding what they needed using

the Library’s online catalog, patrons could request

items and retrieve them at a pickup station at Moffitt

Library. Drawing on the circulating collections of

more than a dozen libraries, Oski Xpress kept the

knowledge flowing as the campus, and the world,

adjusted to a new way of living and learning.

Opening our doors

Data for everyone

Virtual verses

Looking within

Even amid widespread disruption, Berkeley’s research and learning didn’t stop. In the fall,

The Bancroft Library

began offering research

consultations by

appointment, allowing

scholars to safely view

the library’s world-class

treasures in person. Then,

in April, Moffitt became the

first library on campus to

open its doors to students.

With reservations required

and precautions in place,

the reopened Moffitt

proved popular among

students who had been

unable to visit for more

than a year.

The Library Data Services

Program helps students,

faculty, and researchers

of all stripes discover,

access, share, and

preserve data. This year,

the program got a strong

gust of wind in its sails,

growing its partnerships

and unifying its approach

to supporting the UC

Berkeley community.

Through a workshop

series on data analysis, in

collaboration with the Data

Peers program — one of

the many offerings this

year — undergraduates got

the chance to learn from

one another, lowering the

barriers to learning.

This is not poetry’s first

pandemic. The art form

has persisted for thousands

of years and will likely

live as long as there is

passion, anxiety, or hope to

be expressed. The ever-popular Lunch Poems

series likewise weathered

a difficult year, overcoming

isolation by moving its

monthly noontime program

from Morrison Library to an

online format. This year’s

series, hosted by Director

Geoffrey O’Brien, featured

readings by several

renowned poets, including

Pulitzer Prize winner Yusef

Komunyakaa.

Most of the Library’s time is dedicated to supporting

the greater UC Berkeley community. But when last

fall’s fires ravaged California and colored Bay Area skies

ember orange, Library leaders turned their focus inward.

In a Sept. 9 email to the Library’s 300-plus employees,

University Librarian Jeffrey MacKie-Mason spoke to the

cumulative challenges of the year. “Today’s orange skies

and pockets of darkness are ominous and unsettling

for some, beautiful for others, and perhaps a bit of

both for many,” he wrote. “I am not going to pretend

to understand how each of you is feeling today. 2020 is

complex. But I find hope in the fact that, through our

work, the Library is helping build a better, healthier

world.” The email was one of the year’s many internal

messages, sent frequently to celebrate successes, share

updates, and reflect upon the importance of supporting

one another during difficult times.

Cult conversation

History’s red lines

Standards, maintained

A harrowing chapter

No one just up and joins a cult, right? Turns out, the

reality is a bit more complicated than that. Author

Melanie Abrams unearthed this nugget, and more, during

her captivating, free-flowing talk — the centerpiece

of this year’s Luncheon in the Library. In January, at

the virtual event, Abrams lavished the audience with

insights and musings on her latest novel, last year’s finely

wrought Meadowlark, springing from a well of research

and her deep fascination with communes and closed

communities. She also detailed her research process and

spoke about parenting, which she called “the hardest

piece of being human.” Attendee Thomas Schneck ’61

was taken by Abrams’ talk. “She was thoughtful, sincere,

and shared a lot of information — some personal,” he

says. “Overall, her authorship is interesting because it

offers a complex tapestry into spirituality that is very

different from the conventional, at least for me.”

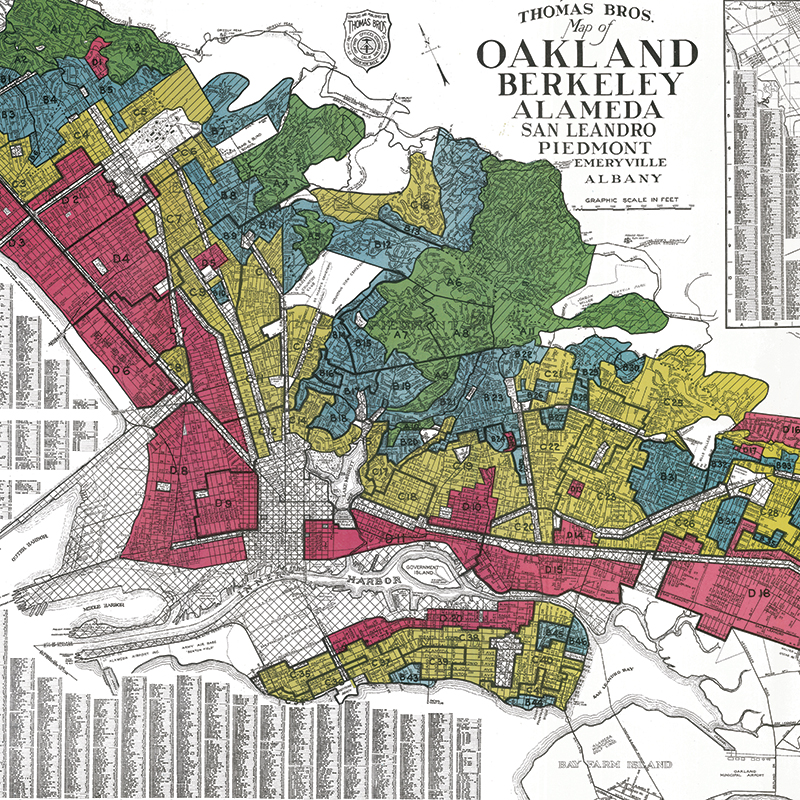

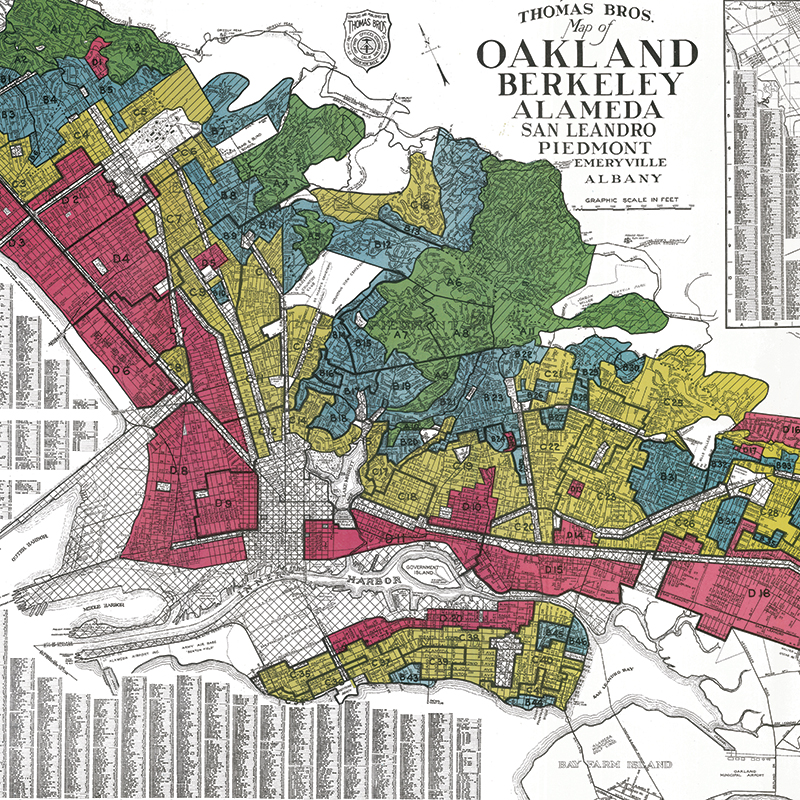

The Library is dedicated to helping people find the

information they need to build a better world. That’s why

the Library’s Berkeley Research Impact Initiative provided

funding to ensure that a study on the insidious long-term

effects of redlining would be free and available to the

public. The study by Berkeley scholars found that babies

born in California neighborhoods historically redlined —

denied federal investments based on the discriminatory

lending practices of the 1930s — are now more likely to

have poorer health outcomes. Rachel Morello-Frosch,

an author of the study and a professor in the university’s

Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and

Management, says she hopes that evidence of redlining’s

legacy can help pave the way for justice — a future in

which the same maps used to disenfranchise people of

color can be used to direct money to affordable housing,

community services, and public health.

While many staff members were working from home,

Doe Library and its interconnected network of libraries

were under the watchful eye of Sam Arrow. As facility

manager for the Doe complex, Arrow was on-site daily

to keep buildings in working order and to respond

to pressing needs. That work included planning for

construction projects and mapping out strategies for

the eventual reopening of buildings in accordance

with city, state, and campus health guidelines. Arrow

commends the crews that contributed to the upkeep of

buildings, despite decreased janitorial and maintenance

staffing. “Without the great work from our dedicated

campus technicians, none of us would be able to get any

work done,” Arrow says. “They come in day after day,

serving the campus to make it a better place to be.”

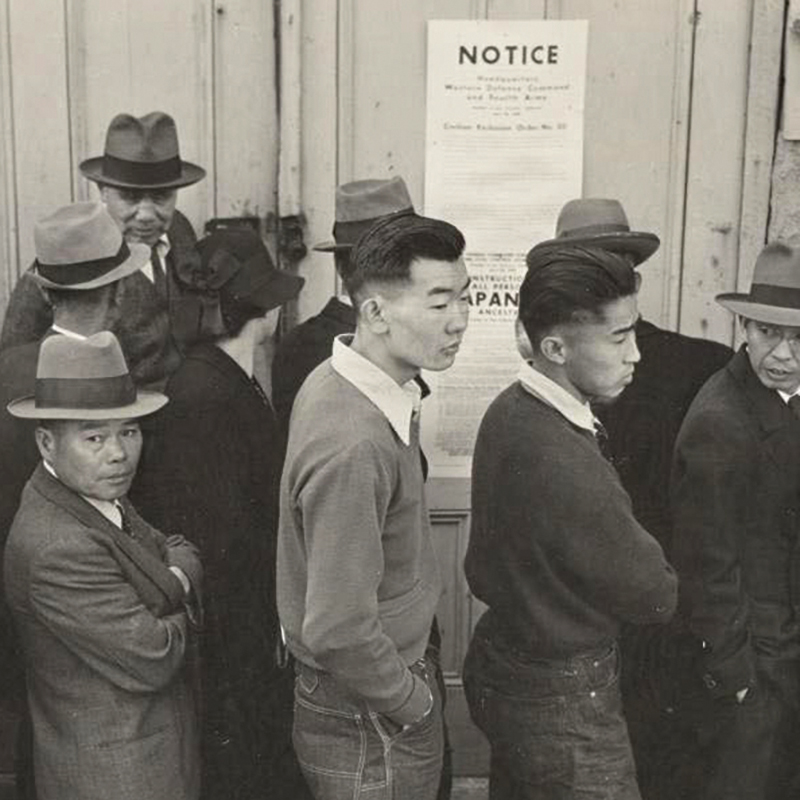

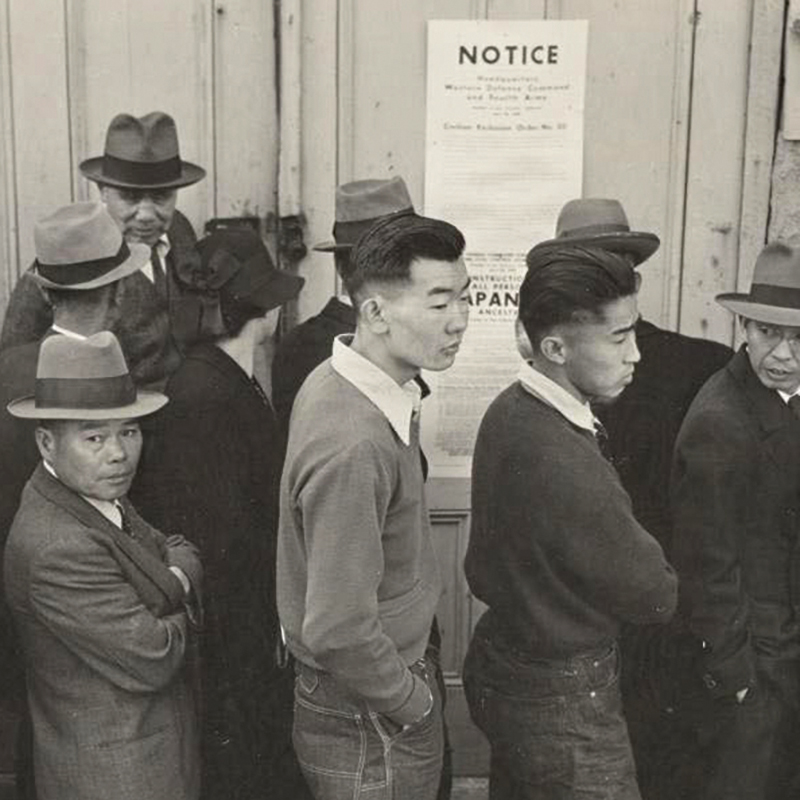

The records, like thousands of candles in the dark, cast

light on lives uprooted. During World War II, the War

Relocation Authority, or WRA, collected information

on each Japanese American who was forcibly confined,

including everything from height and weight to skills and

hobbies. This information now resides at The Bancroft

Library, which is believed to hold the only full set of

original WRA Form 26 individual records of those who

were incarcerated. With funding from a National Park

Service Japanese American Confinement Sites grant,

Bancroft is digitizing the forms. By harnessing machine

learning, a kind of artificial intelligence, the library is

extracting and transcribing the data to build a better,

more accurate, and more complete dataset. This year,

Bancroft digitized nearly 90,000 pages of Form 26

records, of a total numbering over 220,000 pages.

Mapping history

Pandemic protection

Vicarious voyages

An open future

Those searching for truth in the historical record got a

new resource in fall 2020 with the launch of the Library’s

digitized German World War II Captured Maps Collection.

Over the past several years, the Earth Sciences and

Map Library team and its collaborators have cataloged,

scanned, and stored approximately 10,000 of the more

than 21,000 maps in the library’s holdings captured from

the German military during World War II. The maps

are important historical source materials. They allow

geographers, social historians, and genealogists to trace

families and communities during a time of great upheaval.

For researchers studying the history of science and

technology, the maps provide a rich trove for evaluating

the German surveying and mapping effort of the first half

of the 20th century. The maps also document the many

crimes of the Nazi dictatorship, making them invaluable

sources for historians seeking to understand the regime

and its horrific crimes.

If there’s one thing Tony Ayala is used to, it’s change.

“That’s kind of how security works,” says Ayala, head

of Library Security. “When there’s a change in your

environment, you need to respond.” It’s hard to imagine a

bigger change than the constellation of global disruptions

set in motion by the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet even as

Berkeley’s libraries were closed to the public, Library

Security kept a vigilant watch over the facilities and the

countless treasures they hold. Ayala credits his team for

going above and beyond during the early phase of the

pandemic, lending a hand to staff members who weren’t

in the office, helping people gather the belongings

they needed to work from home, and even going on a

“little scavenger hunt” to collect personal protective

equipment across the Library to be donated.

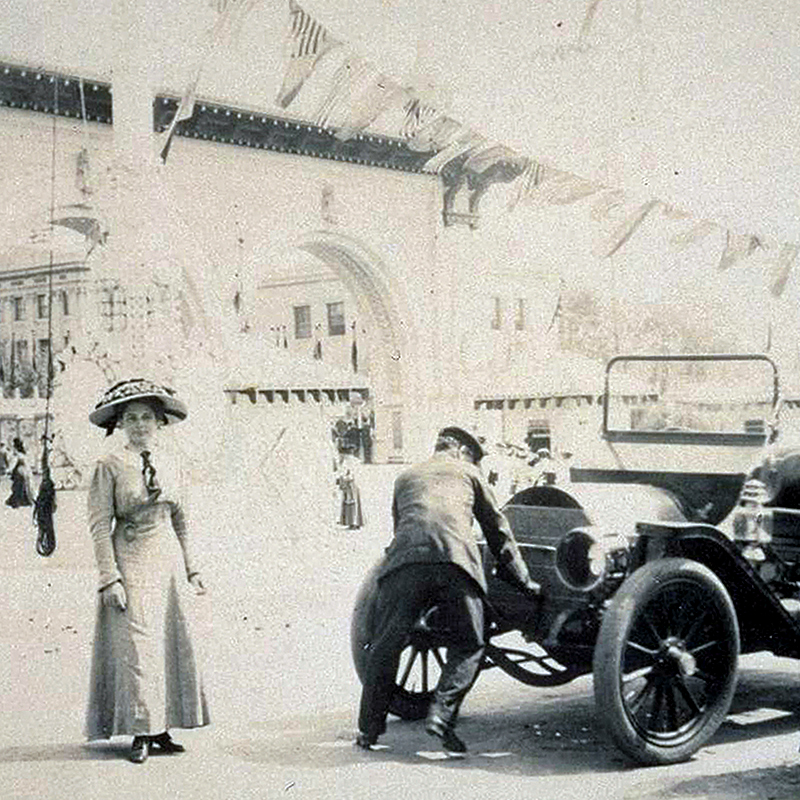

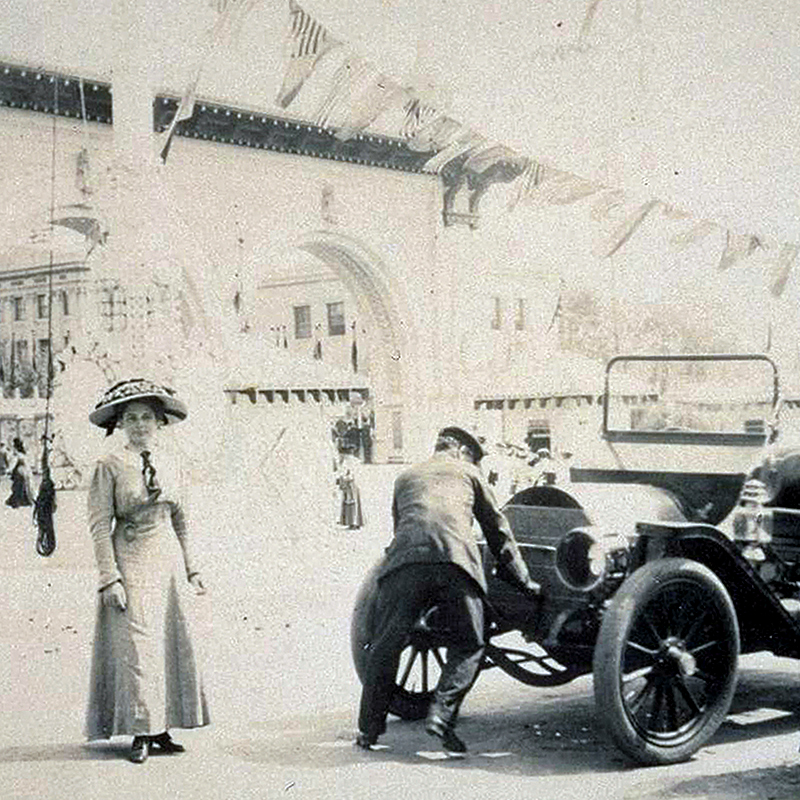

With most travel plans ground to a halt, the Library’s

digital collections offered visitors the chance to enjoy a

tour around turn-of-the-20th-century California through

10,000 postcards. Issued by San Francisco publisher

Edward H. Mitchell, the postcards in the then-newly

digitized collection sent viewers on a journey up the

Pacific Coast and around the American West. The nearly

comprehensive collection was compiled over many

decades by Walt Kransky, who generously donated it

to The Bancroft Library. Many Library staff members

collaborated to bring the Walter Robert and Gail Lynn

Kransky collection of Mitchell’s postcards online, with

work that included making thousands of high-resolution

scans and enhancing them with descriptive data. In

addition to great images, the collection provides insight

into the business of early postcard production and offers

significant opportunity for scholarship and close studies

of visual culture early in the 20th century.

In March, the University of California

announced that it struck a landmark deal with Elsevier, the world’s

biggest academic publisher. The deal, the largest of its kind in

North America, makes more UC research free for anyone around

the world who wants it, and nudges the scholarly publishing

industry toward a future where knowledge is available to everyone.