At a historic panel in 1978 called “Black Women Writers and Feminism,” June Jordan defined Black feminism as an act of love. She said: “I am a feminist, and what that means to me is much the same as the meaning of the fact that I am Black. It means that I must undertake to love myself and respect myself as though my very life depends upon self-love and self-respect. … It means that I am entering my soul in a struggle that will most certainly transform all the peoples of the earth: the movement into self-love, self-respect and self-determination is the movement now galvanizing the true majority of human beings everywhere.”

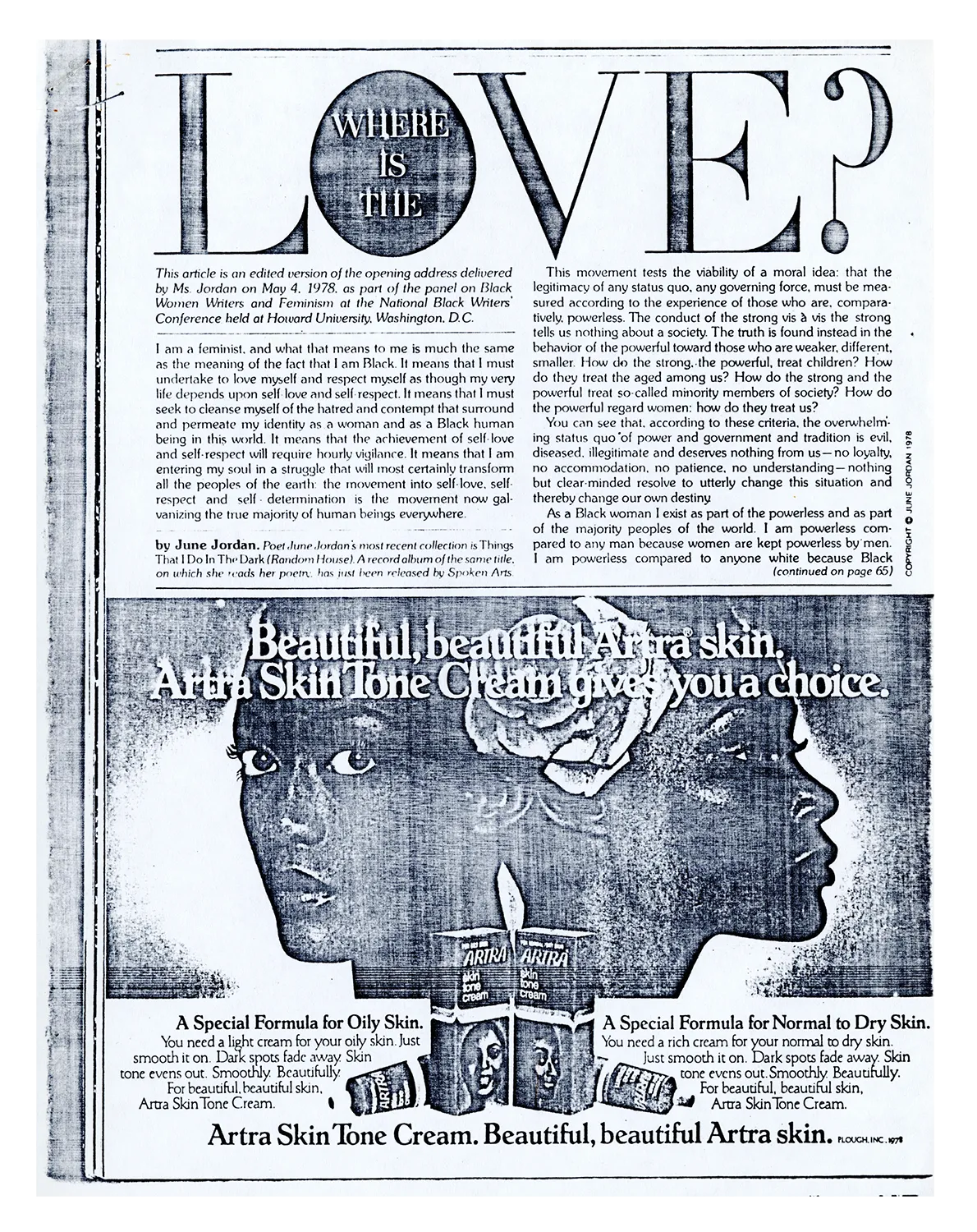

Where Is the Love?

This article is an edited version of the opening address delivered by Ms. Jordan on May 4, 1978, as part of the panel on Black Women Writers and Feminism at the National Black Writers’ Conference held at Howard University, Washington D.C.

I am a feminist, and what that means to me is much the same as the meaning of the fact that I am Black. It means that I must undertake to love myself and respect myself as though my very life depends upon self-love and self-respect. It means that I must seek to cleanse myself of the hatred and contempt that surround and permeate my identity as a woman and as a Black human being in this world. It means that the achievement of self-love and self-respect will require hourly vigilance. It means that I am entering my soul in a struggle that will most certainly transform all the peoples of the earth: the movement into self-love, self-respect and self-determination is the movement now galvanizing the true majority of human beings everywhere.

This movement tests the viability of a moral idea: that the legitimacy of any status quo, any governing force, must be measured according to the experience of those who are, comparatively, powerless. The conduct of the strong vis à vis the strong tells us nothing about a society. The truth is found instead in the behavior of the powerful toward those who are weaker, different, smaller. How do the strong, the powerful, treat children? How do they treat the aged among us? How do the strong and the powerful treat so-called minority members of society? How do the powerful regard women: how do they treat us?

You can see that according to these criteria, the overwhelming status quo of power and government and tradition is evil, diseased, illegitimate and deserves nothing from us—no loyalty, no accommodation, no patience, no understanding—nothing but clear-minded resolve to utterly change this situation and thereby change our own destiny.

As a Black woman I exist as part of the powerless and as part of the majority peoples of the world. I am powerless compared to any man because women are kept powerless by men. I am powerless compared to anyone white because Black (continued on page 65)

“Where Is the Love?,” “Black Women Writers and Feminism” panel, 1978, Carton 6:50, Barbara Christian papers, BANC MSS 2003/199 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.