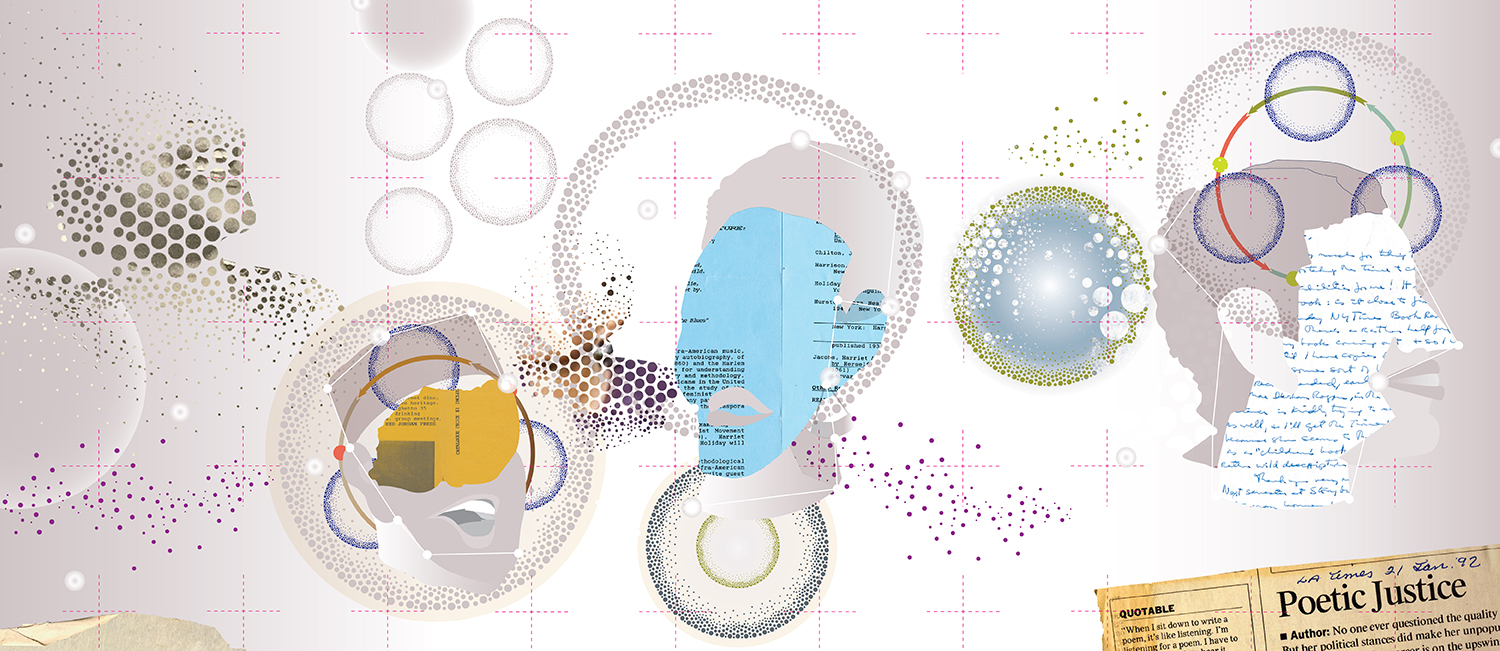

Exploring papers, poetry, photographs, and more

Black feminist theory has inspired generations of students, scholars, activists, and artists at UC Berkeley and beyond.

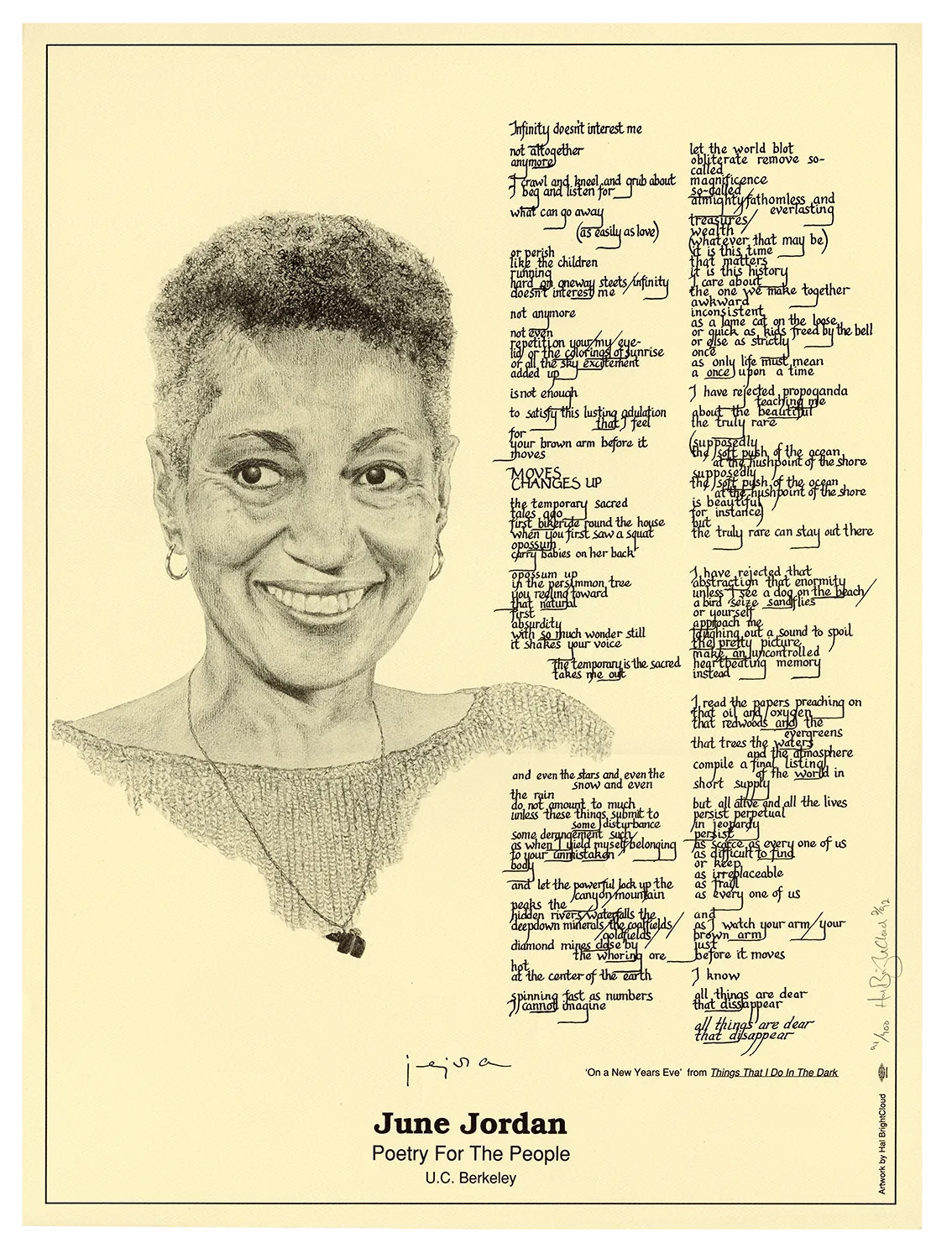

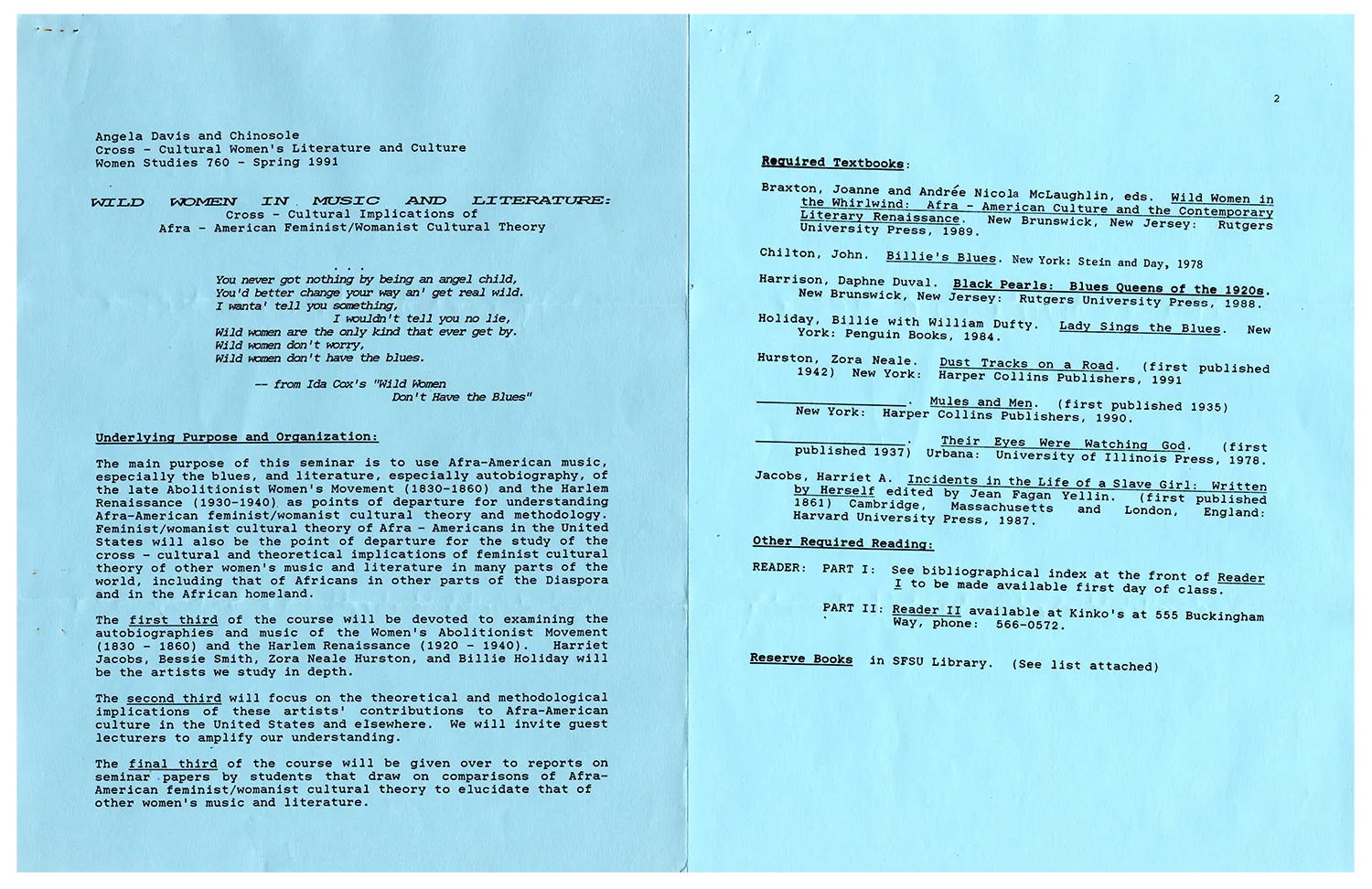

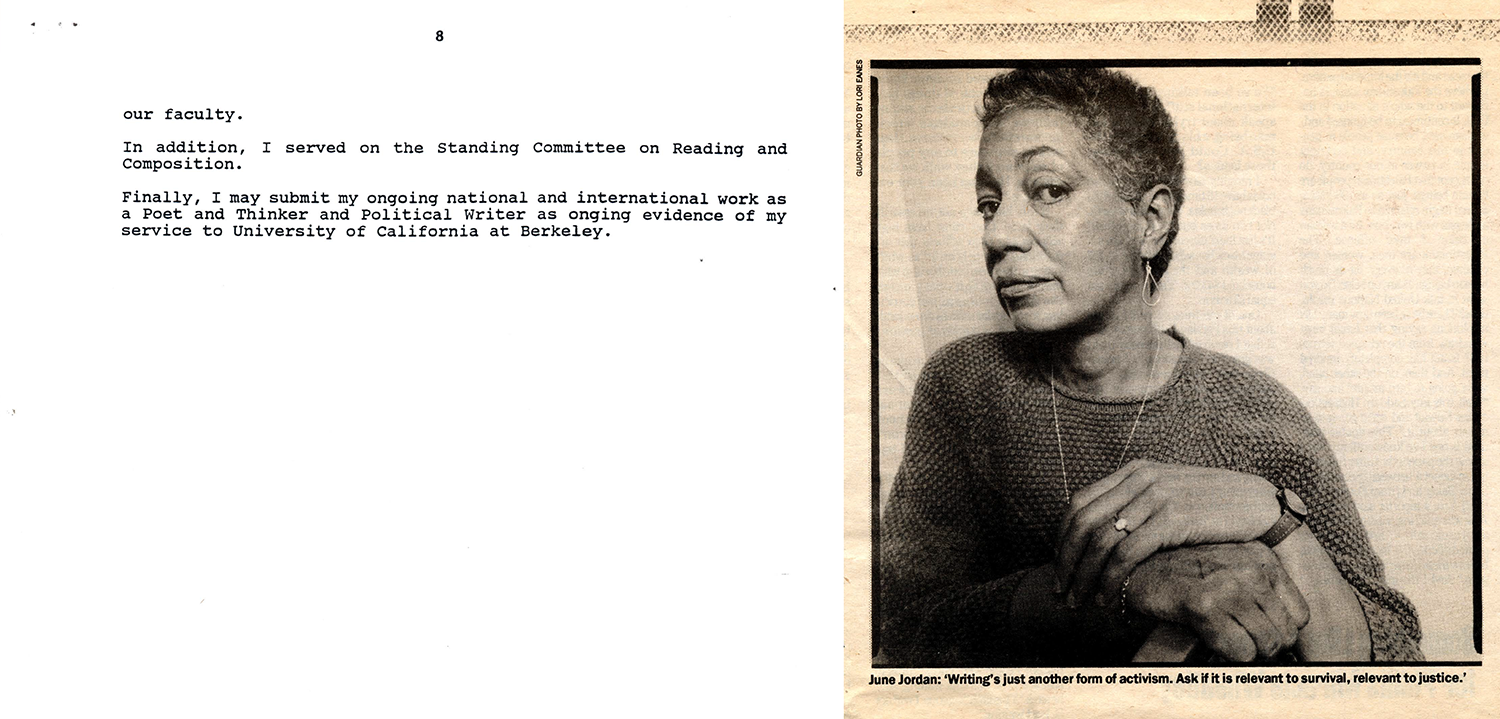

In 2021-22, the Department of African American Studies & African Diaspora Studies launched the Black Studies Collaboratory and held a series of events celebrating Black feminist visionaries and faculty members Barbara Christian and June Jordan. Christian was a literary scholar who was instrumental in establishing African American and African diaspora studies at Berkeley. Jordan, an activist and poet, founded Poetry for the People, or P4P, which introduces students to the power of poetry to change the world.

Inspired by the Black Studies Collaboratory and these visionaries, we explore the legacies of Christian, Jordan, and Black feminism through constellations of archives from the Ethnic Studies Library and The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. We highlight Christian’s own papers; records from the P4P program; collections related to activist, author, and publisher SDiane Bogus and her feminist press; and the papers of Red Jordan Arobateau, a trans man, working-class poet, storyteller, and publisher who found community and support in Black lesbian feminist circles.

Click on the images below to learn more about Black feminism through letters, photos, poems, and more.

Independent bookstores and publishing

To sustain their vision and voices, Black feminists and feminists of color created a vast and decentralized network of independent enterprises, including bookstores, presses, and collectives. Rather than subject their work to the editorial whims of the mainstream publishing industry, they turned to a do-it-yourself and do-it-together ethic, creating separate and autonomous spaces where they were able to protect the integrity of their work and relationships.

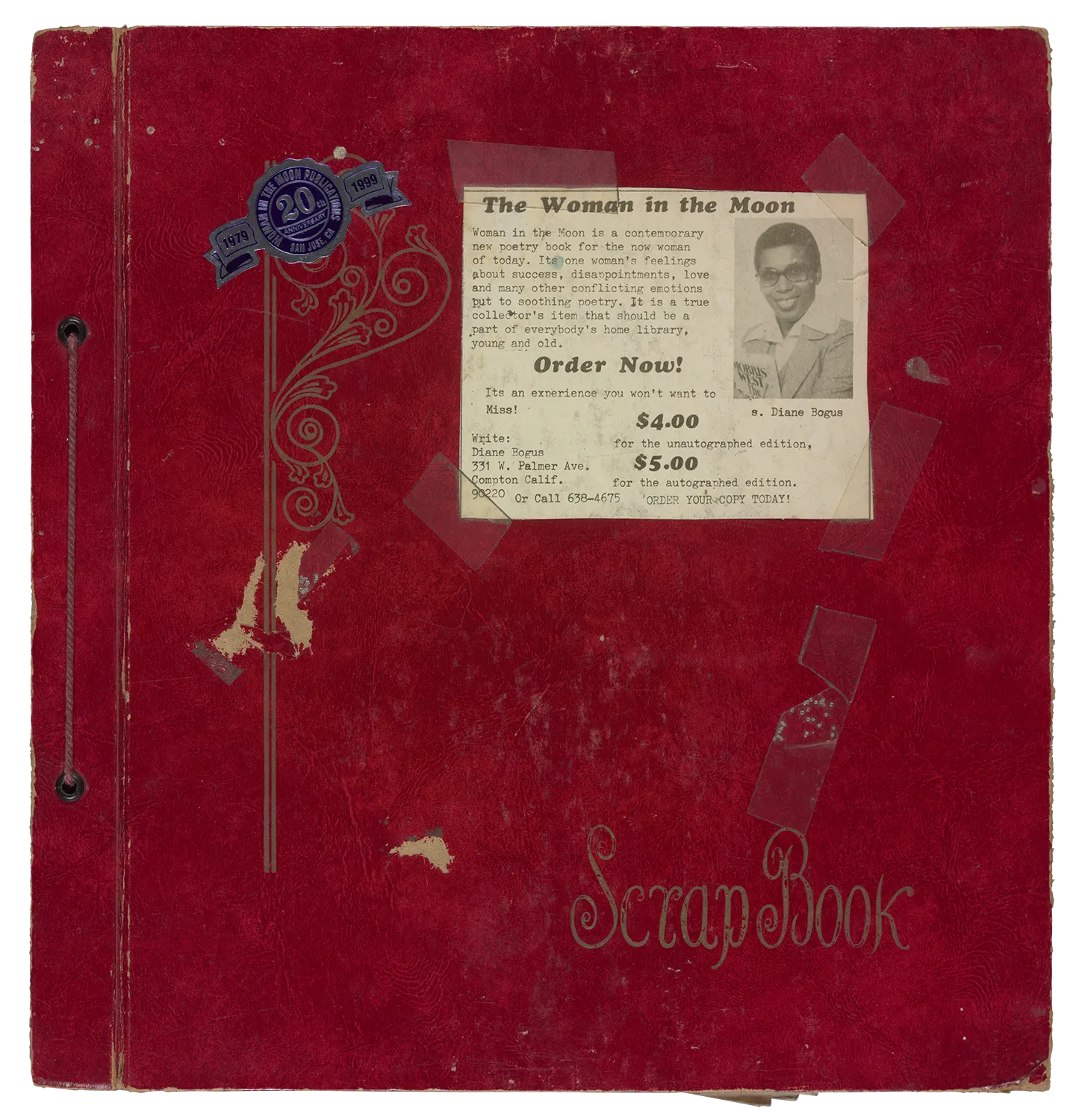

From 1979 through 1999, SDiane Bogus (pictured seated on the right) was editor-in-chief and publisher of Woman in the Moon Publications, a feminist and spiritual book company, The press published over 30 books of poetry, fiction, and non-fiction by and about people of color, LGBTQ+ people, and prisoners. In many ways, relationships and friendships formed and nurtured strengthened the political movement.

Both the SDiane Bogus papers and Woman in the Moon Publications records contain scrapbooks in which Bogus documented her life history and memories. Many feminists engaged in a practice of scrapbooking as a way to document their stories and collect ephemera from their lives.

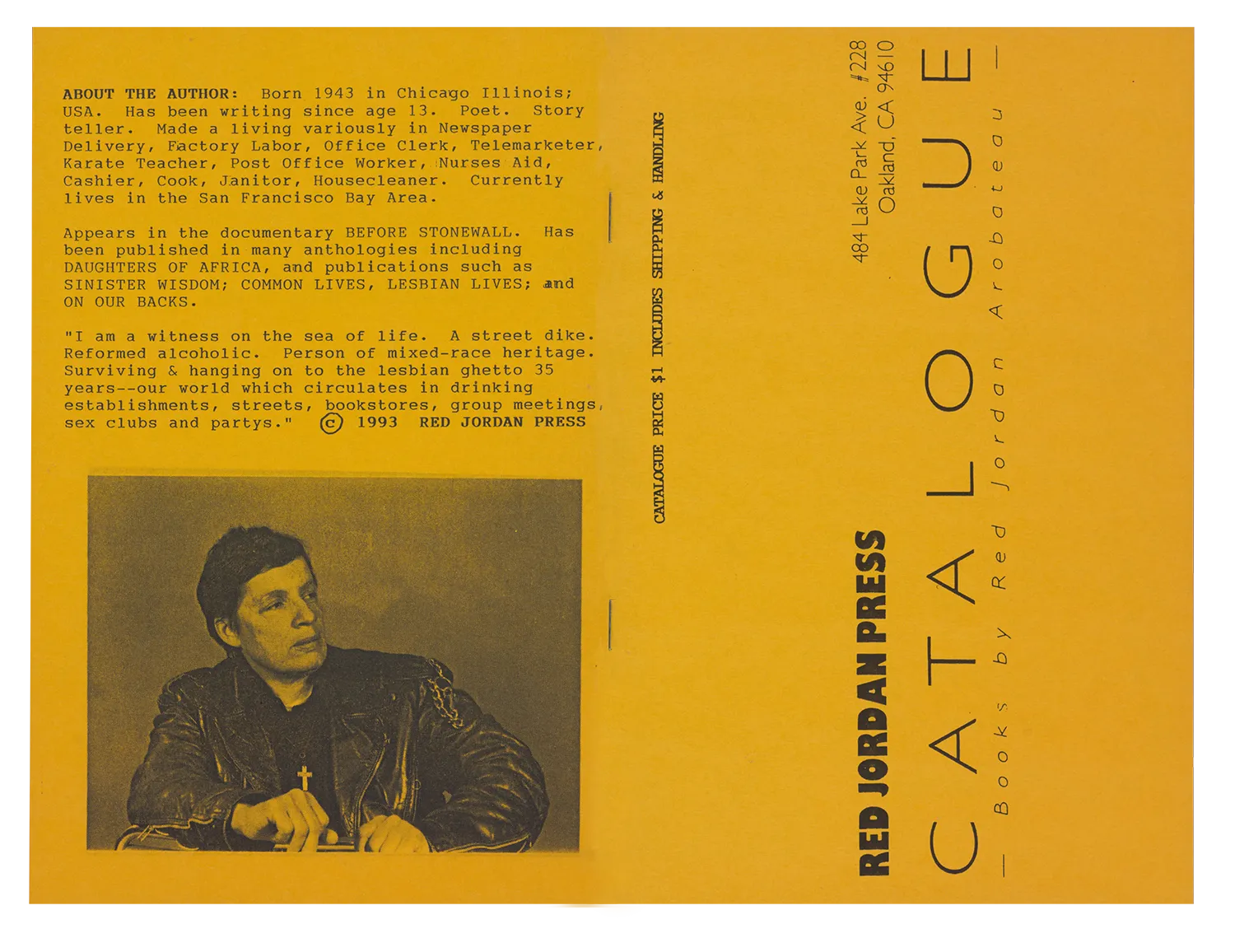

Red Jordan Arobateau was a working-class poet, storyteller, and self-described writer of “dyke novels.” In order to share his writing, Arobateau worked with small gay and lesbian presses and also created his own press, the Red Jordan Press. The erotic content was initially too much for established gay and lesbian publishers, so he often worked odd jobs and sold his handmade books in lesbian bars, feminist bookstores, and on the streets.

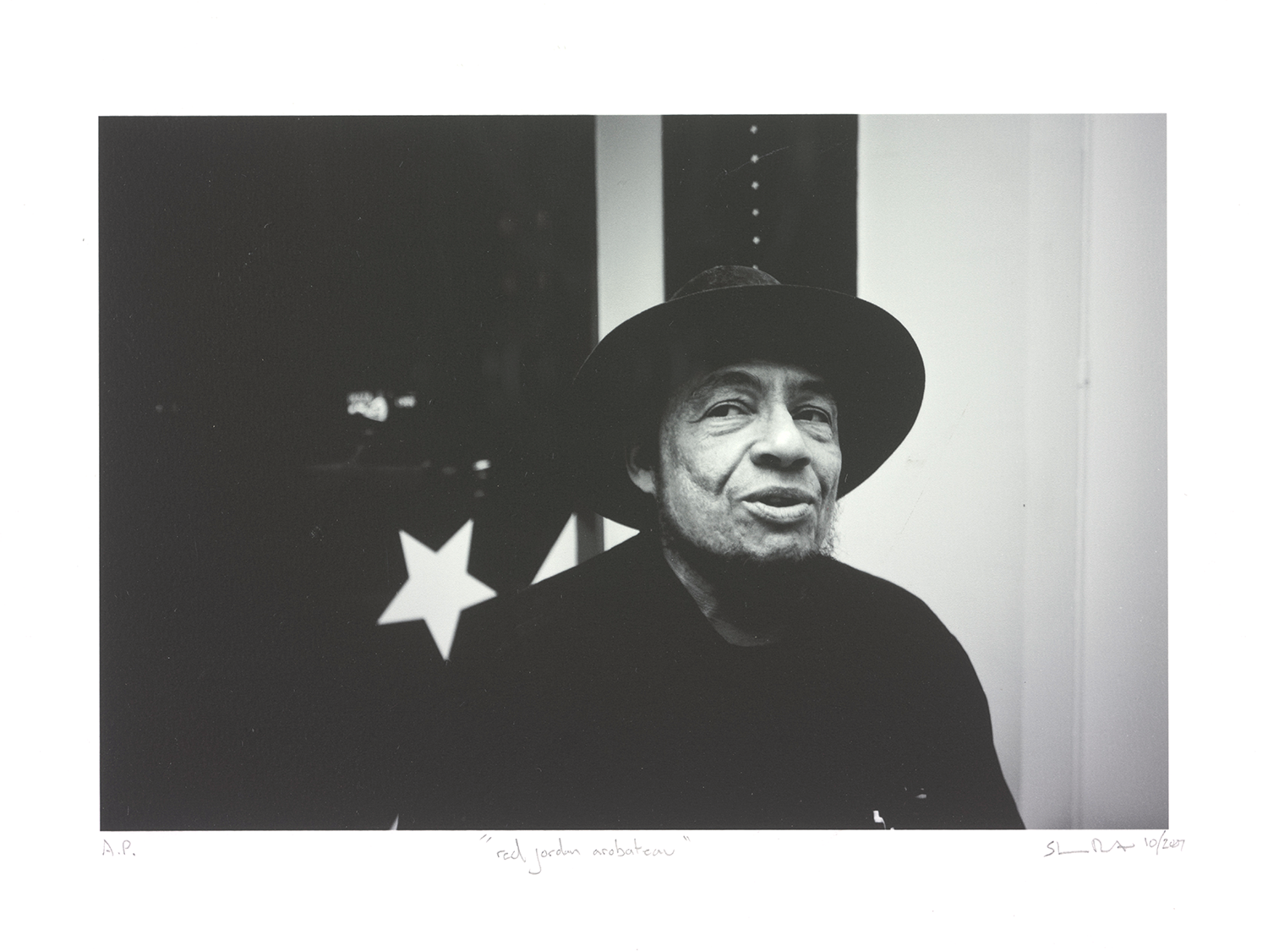

Pictured here in 2007 at the age of 64, Red Jordan Arobateau represents an important part of the Black feminist movement. As a trans man, Arobateau found community and support in Black lesbian feminist circles and spaces.

Spirituality and lived experiences

Black feminism is a multifaceted social movement that is rooted in the lived experiences of Black women, and draws heavily on the experiences and contributions of Black lesbians and bisexual women. While it is primarily thought of as a political and socioeconomic movement, Black feminists and feminists of color have also found solace and strength in the healing arts. By collectively resisting violence and oppression, they focus on building a new world rooted in the values of love, interdependence, and self-determination.

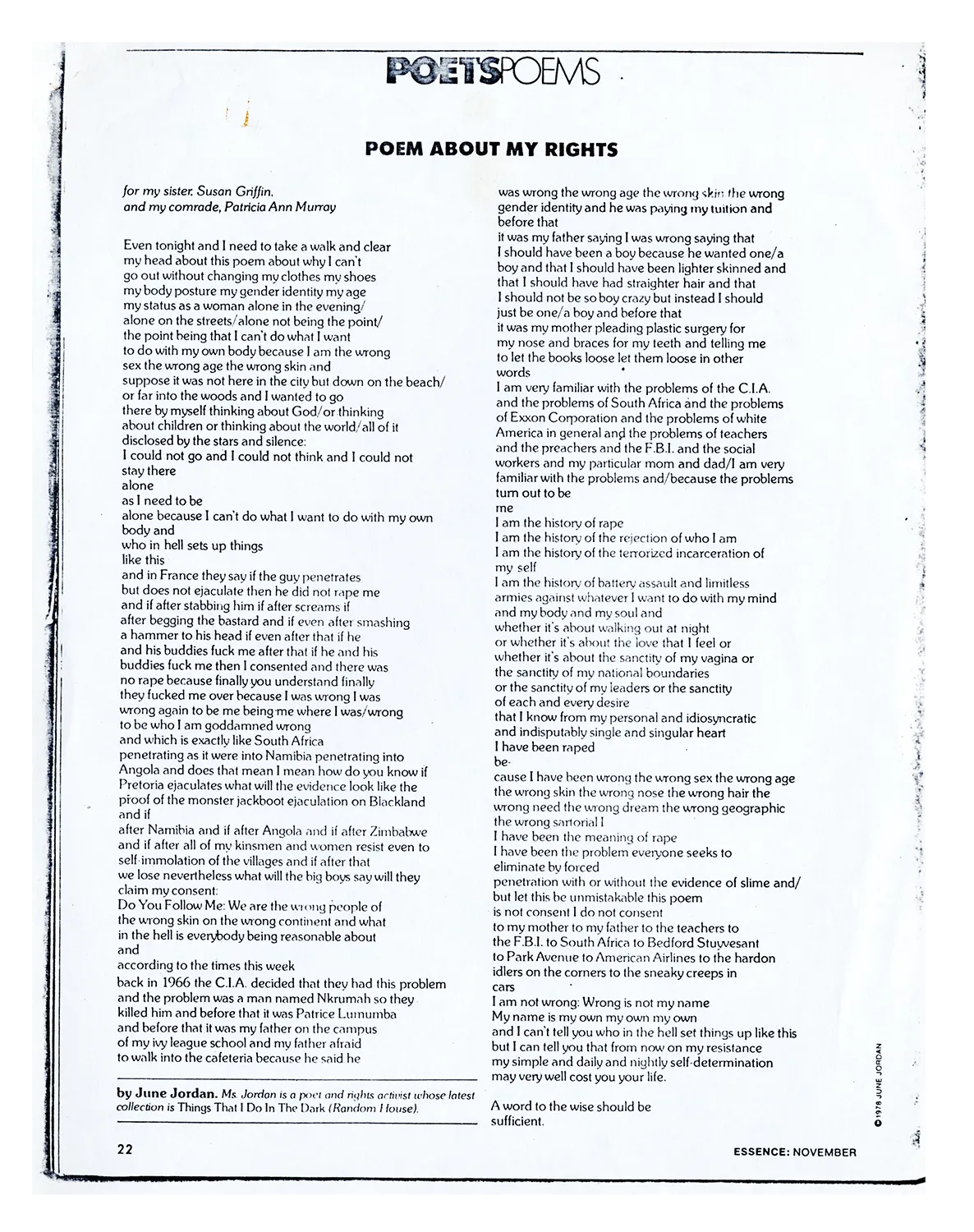

June Jordan’s “Poem about My Rights,” published in 1978 by Essence magazine, articulates her experiences as a self-identified Black bisexual woman and survivor of violence. In the last lines, she emphasizes how “daily and nightly self-determination” is her form of resistance.

Jordan writes: “I am not wrong: Wrong is not my name / My name is my own my own my own / and I can’t tell you who in the hell set things up like this / but I can tell you that from now on my resistance / my simple and daily and nightly self-determination may very well cost you your life.”

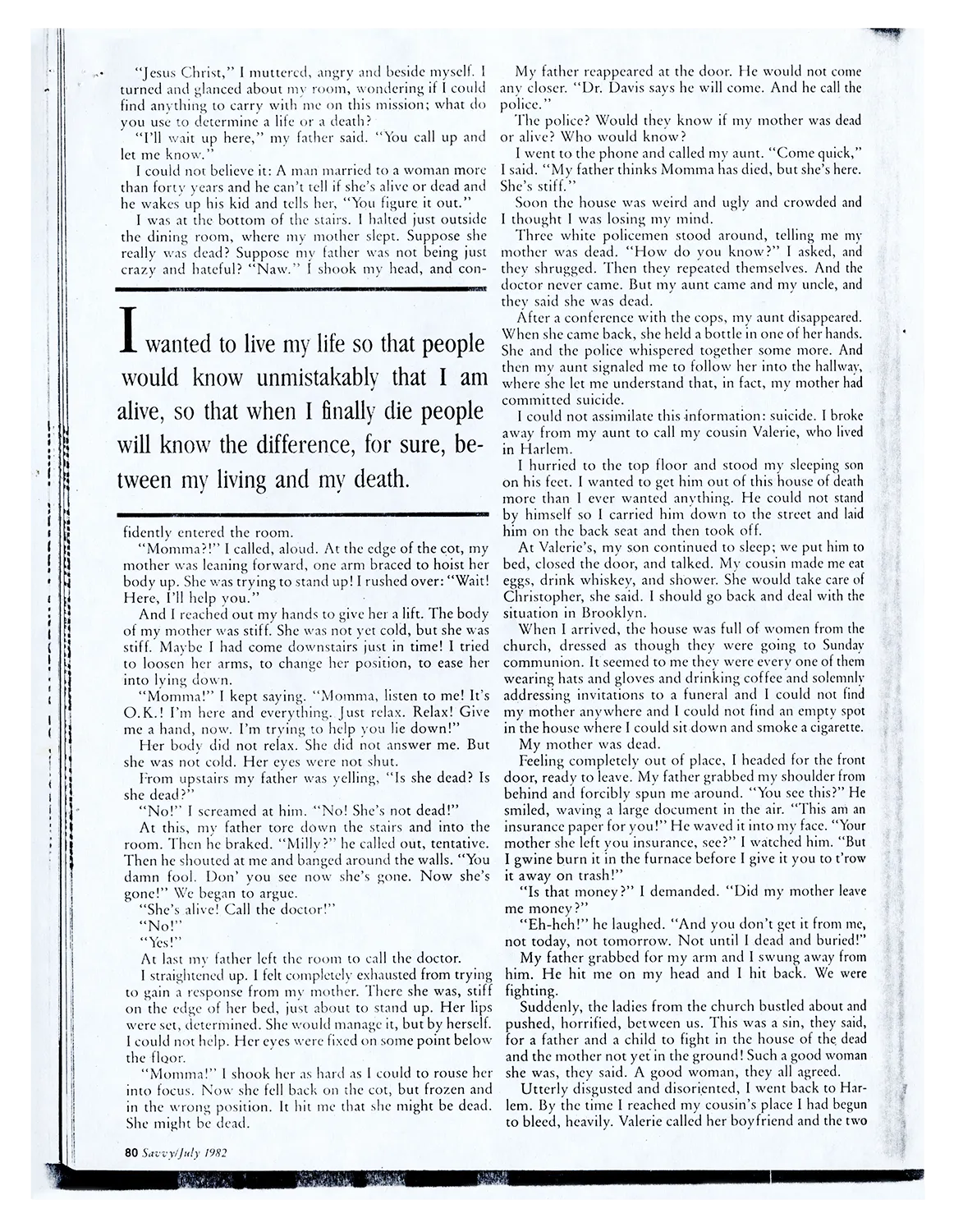

In “A Legacy of Strength,” published by Savvy in 1982, Jordan writes: “I wanted to live my life so that people would know unmistakably that I am alive, so that when I finally die people will know the difference, for sure, between my living and my death.” Jordan’s writing captures the “life and death” realities of being a Black bisexual woman. As evident in her work, poetry and writing was a form of breathing and a confirmation of aliveness.

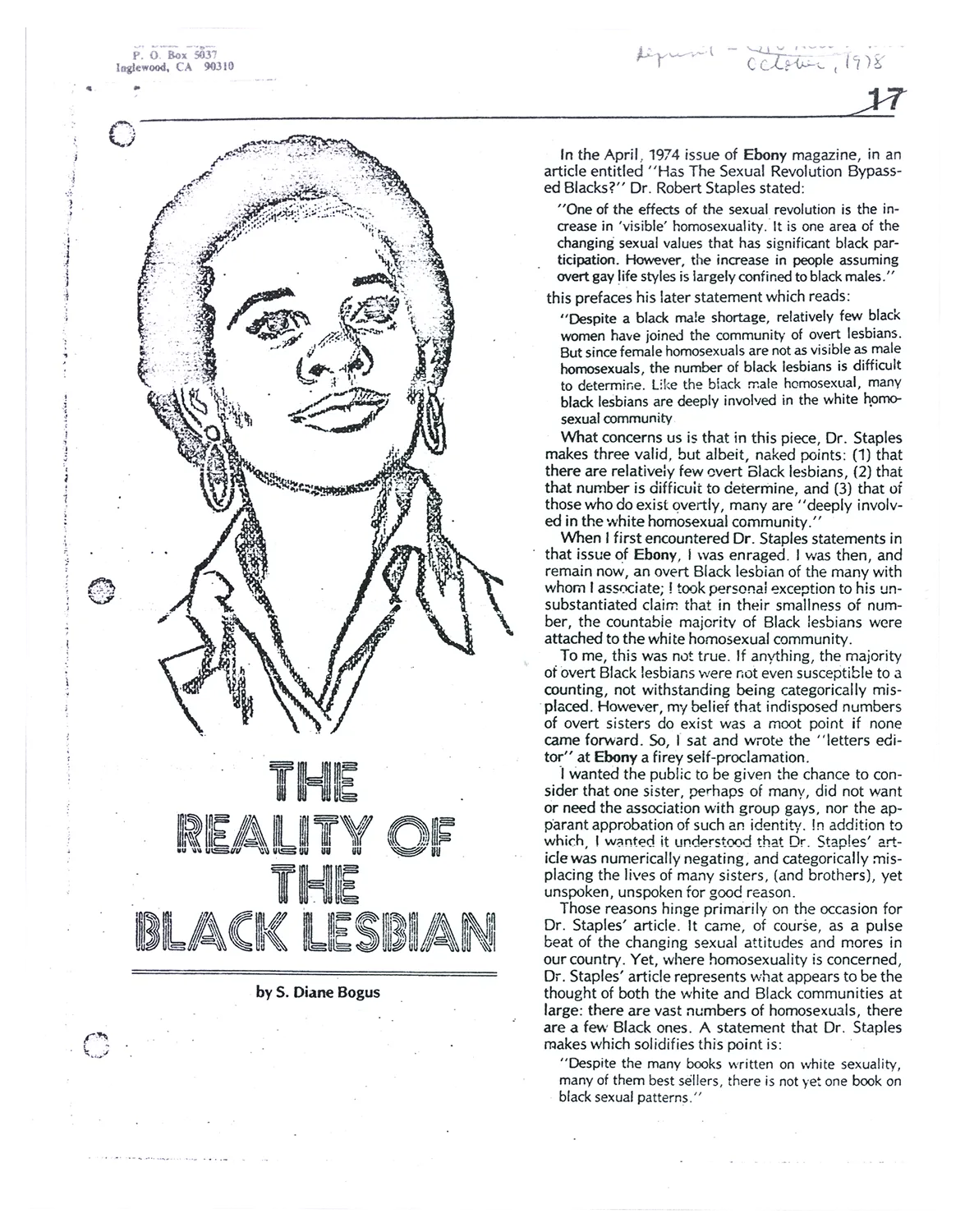

An excerpt from this essay by author and publisher SDiane Bogus touches on “intersectionality,” a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw and rooted in Black feminism: “Because I have come to prefer not to spend all my time defining or explaining my right to be Black, gay or whatever, I could not ever be wholly enmeshed in a single group ideology.” Intersectionality affirms that all people hold multiple identities that cannot be divided into single issues. Black feminist Audre Lorde speaks to this when she writes, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

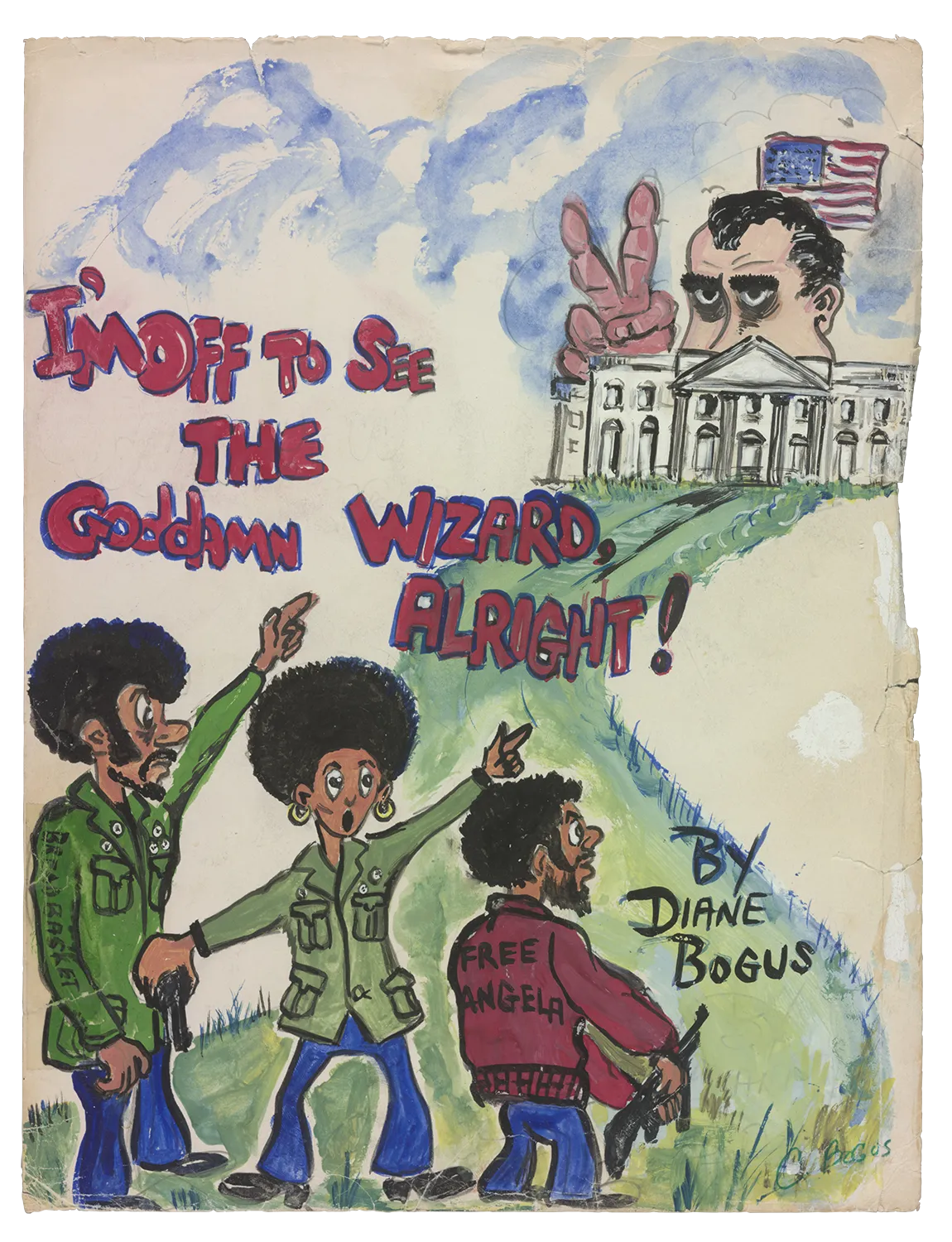

Originally published in 1971, I’m Off to See the Goddamn Wizard, Alright! is described by Diane Bogus, later known as SDiane (“es-di-ann), as “a collection of first poems for black people and those to whom it may concern.” Bogus writes “The wizard to whom I refer is sometimes the ominous ‘they’ I use repeatedly in my book. ‘They’ are white people. Sometimes the wizard is an untruth, an unreality, a misbelief; however, for the most part, the wizard is any and all myths perpetrated by white people and tenaciously, without question, adhered to by Blacks.” The “wizard behind the curtain” represents the struggle of Black feminists as they articulate the truth of their lived experiences to dispel oppressive beliefs.

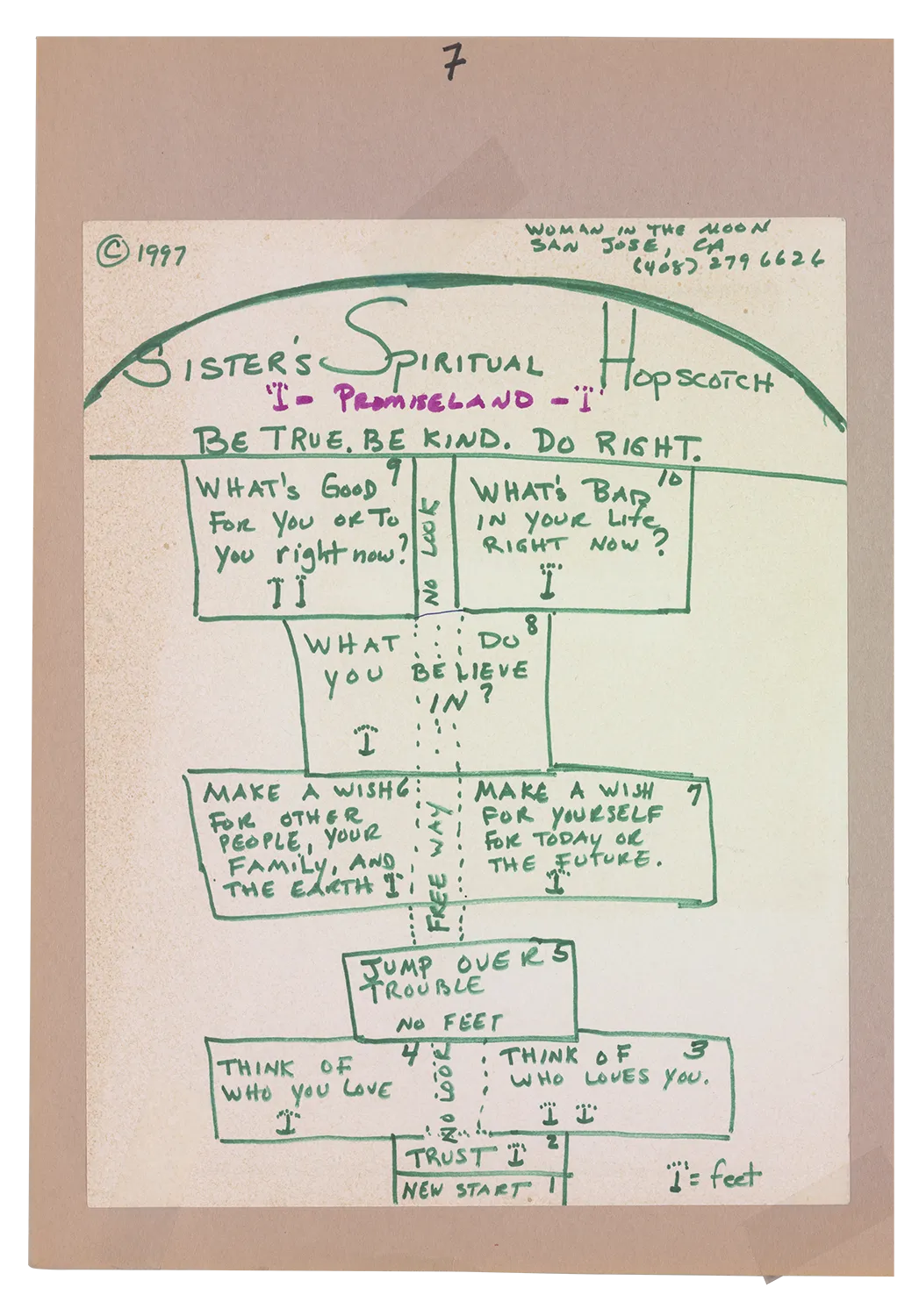

In the 1990s, Bogus’ focus shifted toward the healing arts. For Black feminists and feminists of color, activism had a deep-seated spiritual connection that encompassed a politics of care and healing. Bogus, also known as the Oracle/Sister Soul-Joiner, was a trained massage therapist, pranic healer, and reiki and hypnosis practitioner. The Sister’s Spiritual Hopscotch diagram, shown here, illuminates the ways in which Black feminism sought to encourage different ways of thinking about “what loves you” and “what’s good for you.”

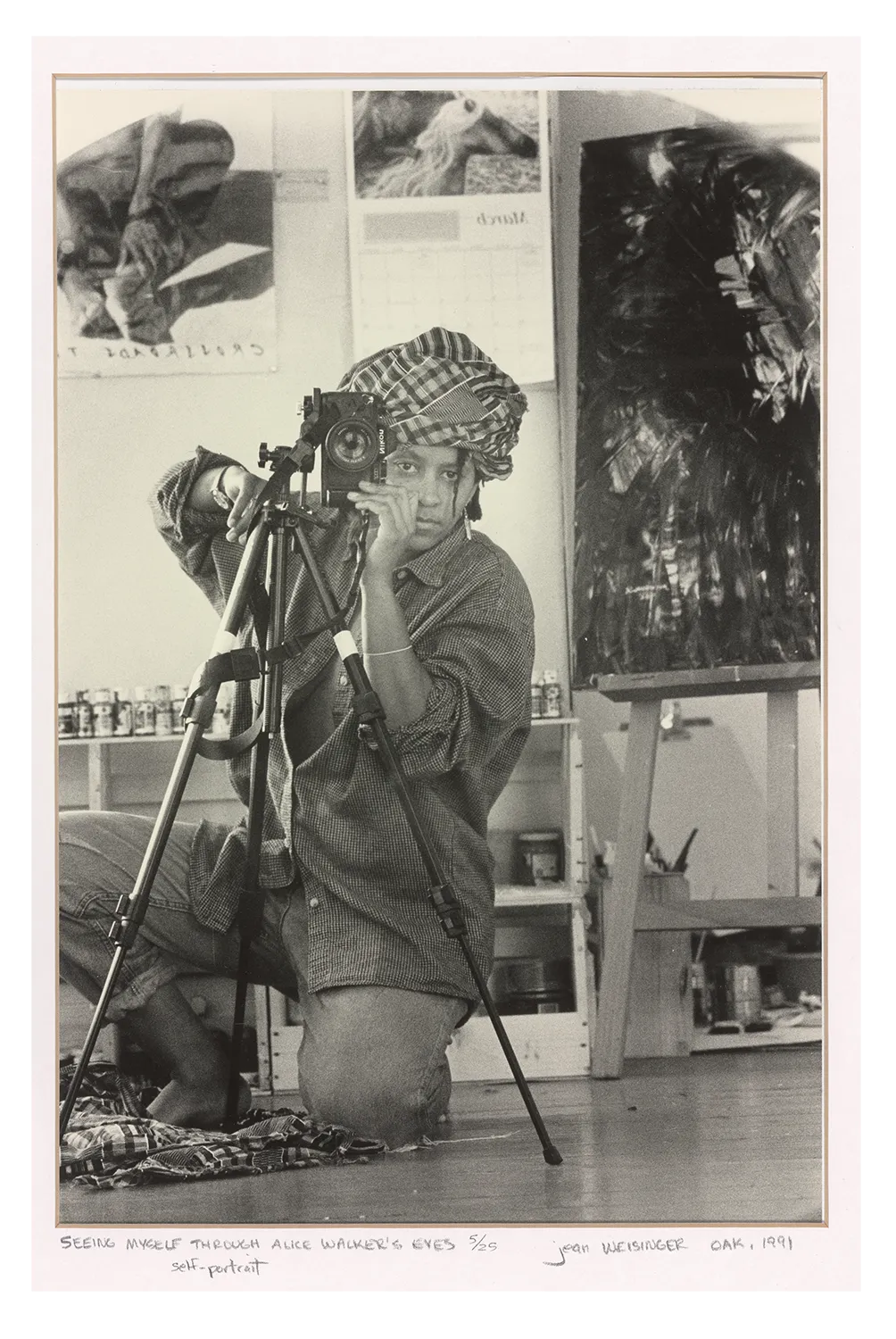

Black feminists and feminists of color have argued that our society and world is viewed through a “white male gaze.” By decentering this gaze and looking “through each other’s eyes,” feminists sought to see the world in a new light.

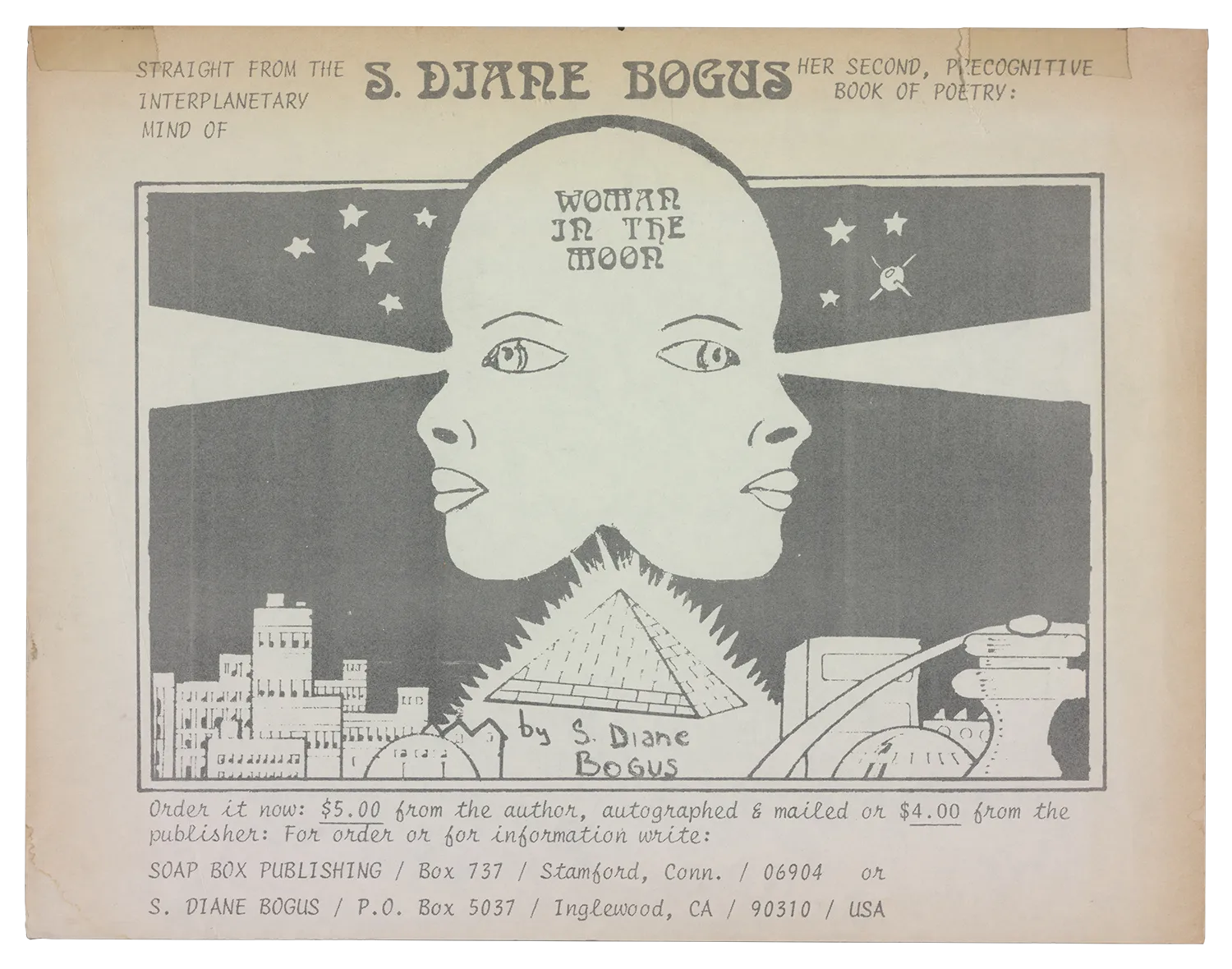

Pasted on the interior cover of a scrapbook, this flyer from Woman in the Moon Publications, the feminist press founded by SDiane Bogus in 1979, incorporates an aesthetic and vision of Afrofuturism, described by scholar and futurist Ytasha L. Womack as “an intersection of imagination, technology, the future, and liberation.” The Press ceased operations in 1999, after publishing more than 30 books of poetry, fiction, and non-fiction by and about people of color, LGBTQ+ people, and prisoners on topics in women’s studies, health, and spirituality.

The power of poetry

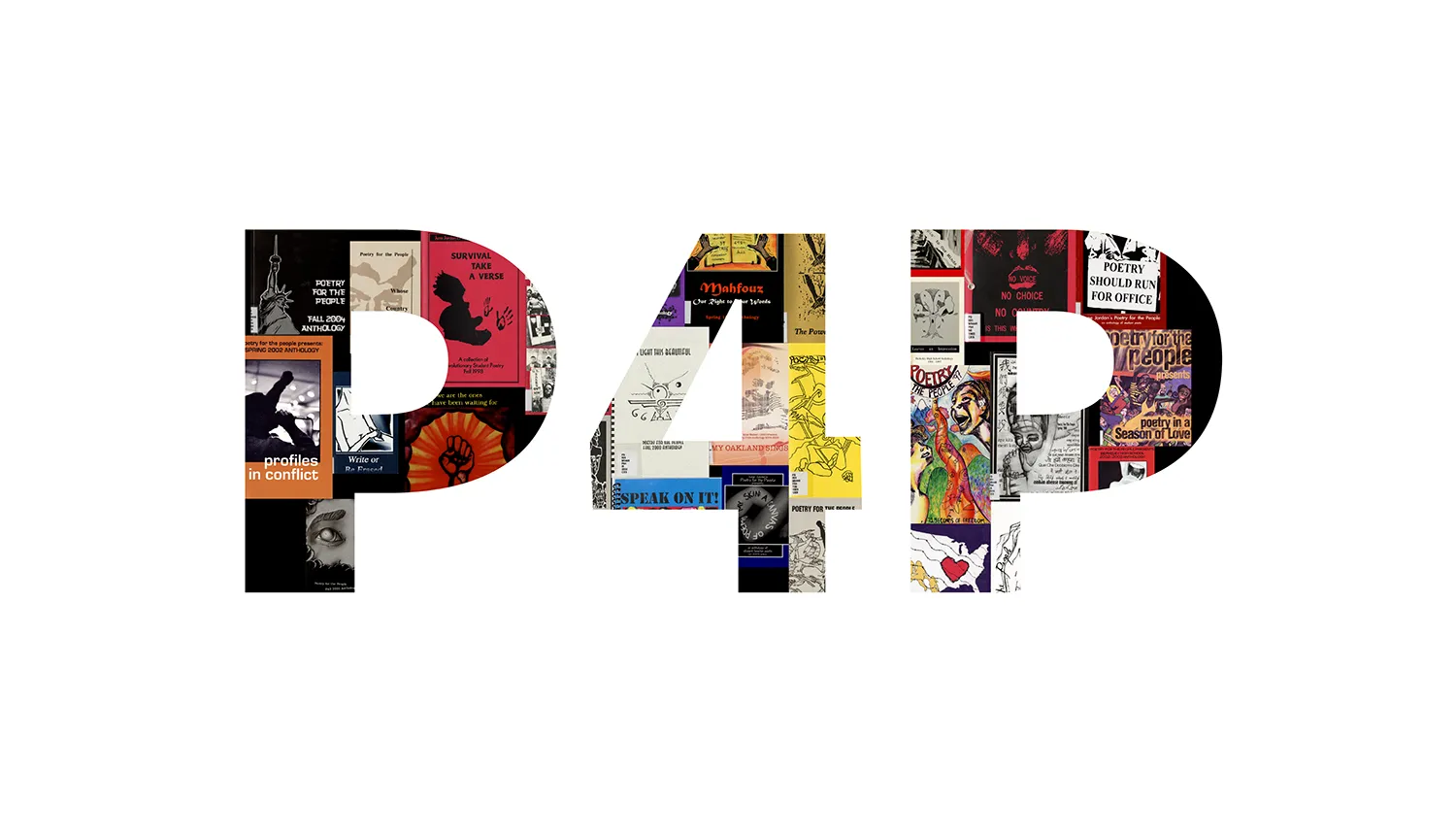

A central theme of Black feminism is an emphasis on writing as a form of resistance, healing, and self-determination. June Jordan founded Poetry for the People, or P4P, in 1991. The arts and activism program focuses on reading, writing, and teaching poetry, and bridges the gap between UC Berkeley and the surrounding community by working with young adults, schools, community groups, and activists throughout the Bay Area.

Intimacy and the ephemerality of love and life are themes within Jordan’s poetry and work. Amid the pain of loss and grief that is present within the poem, she also invokes collective joy and agency. As Jordan writes, “It is this time that matters / it is this history I care about / the one we make together.”

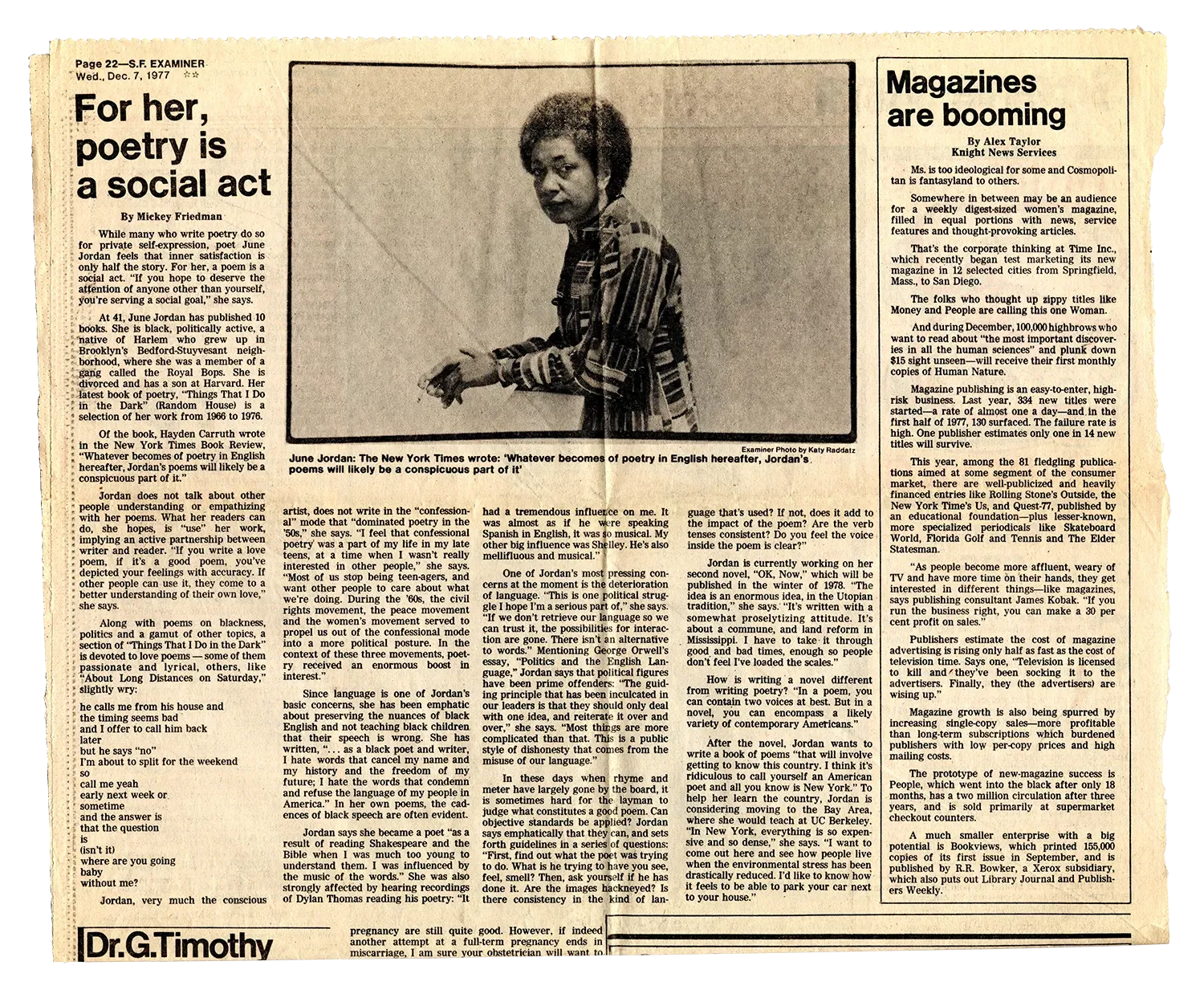

For Jordan and other Black feminists, poetry was not just an individual exercise but a “social act”, a form of collective and personal resistance. Jordan sought to nurture an active partnership between writer and reader, which she actualized in Poetry for the People ( P4P) classes. The students in these classes published anthologies and hosted readings to share their voices and perspectives with one another and a wider community. Under the leadership of director Aya de León in the Department of African American Studies & African Diaspora Studies, the program carries on with Jordan’s spirit.

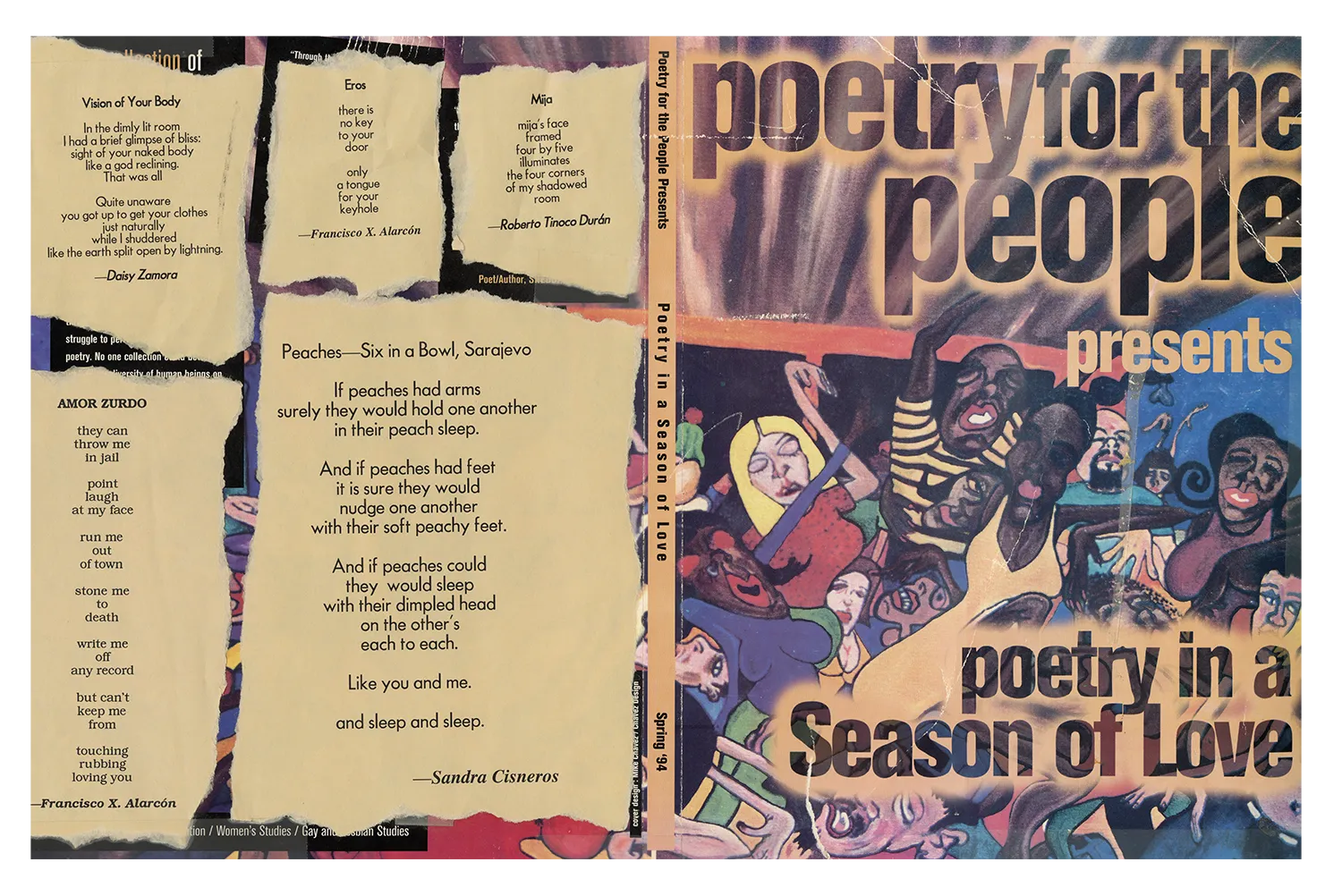

Poetry for the People’s spring 1994 anthology, Poetry in a Season of Love, is repurposed as a poster, using layered poems revolving around the theme of love — a core principle of Black feminism.

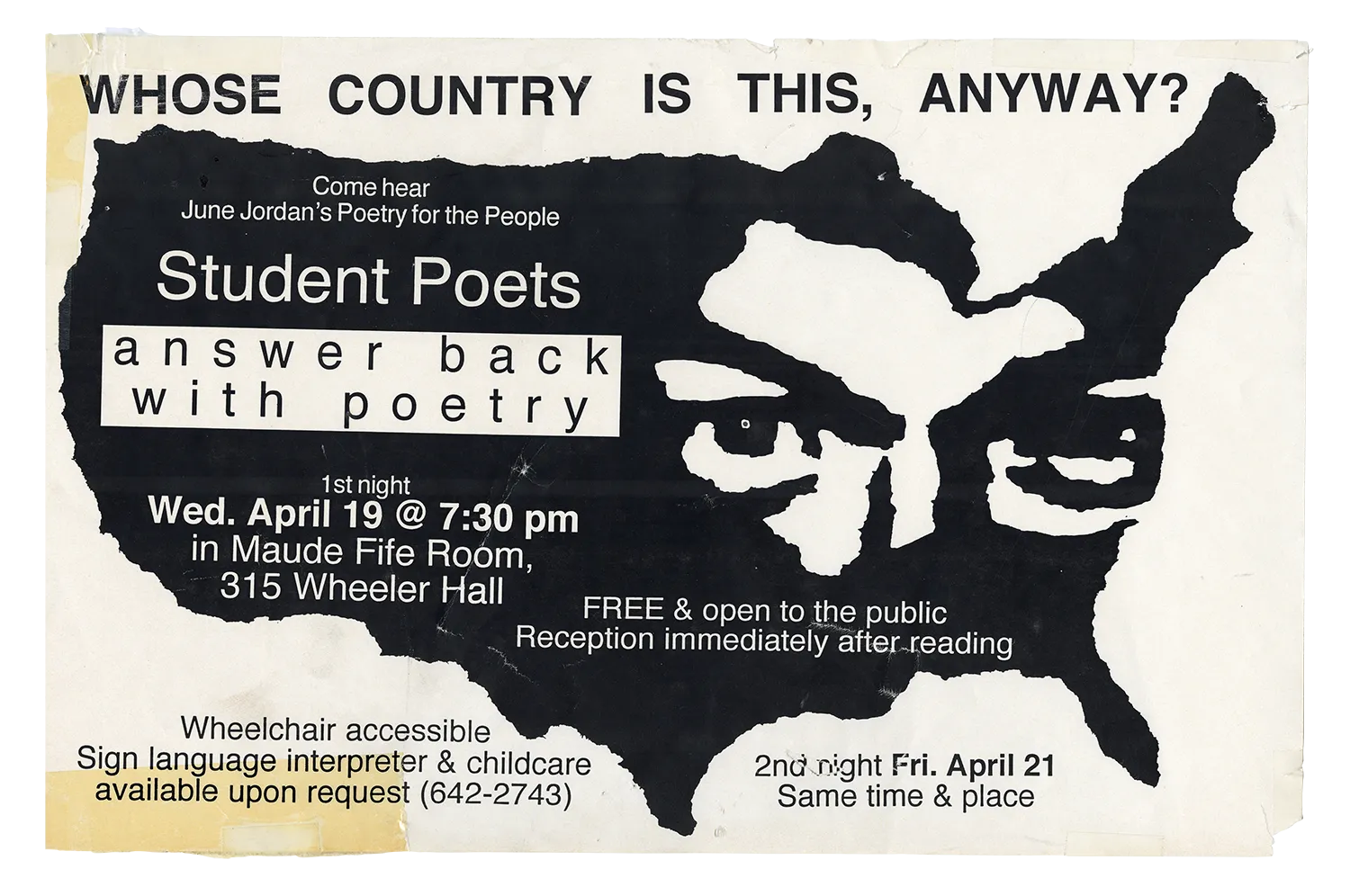

“Come hear June Jordan’s Poetry for the People Student Poets answer back with poetry.” This poster for a Poetry for the People reading illustrates how student poets “answer back with poetry” when their sense of belonging is questioned.

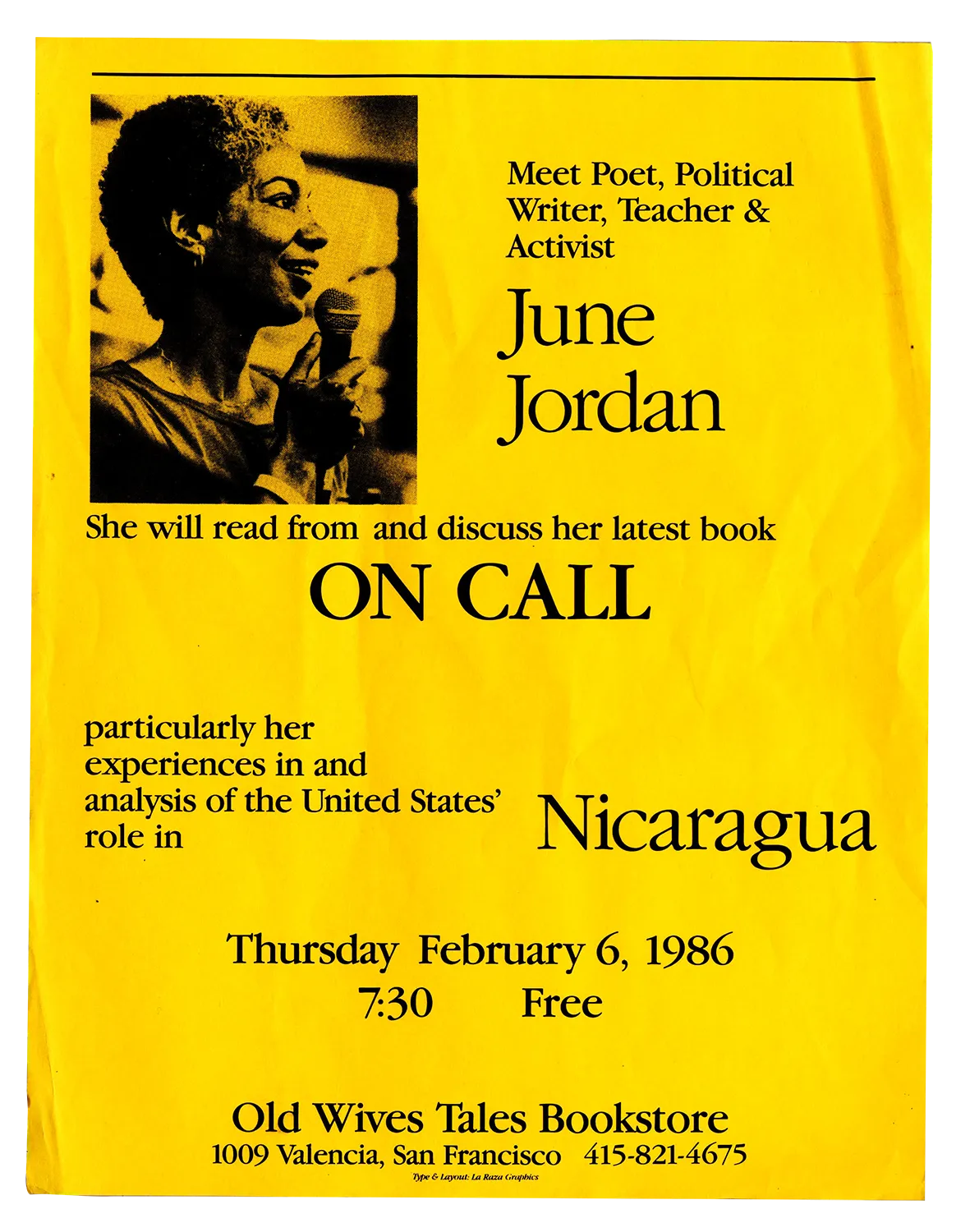

At this event, Jordan talked poetry and international politics at the Old Wives Tales, a lesbian feminist bookstore on Valencia Street in San Francisco, which was once home to a busy corridor of lesbian establishments.

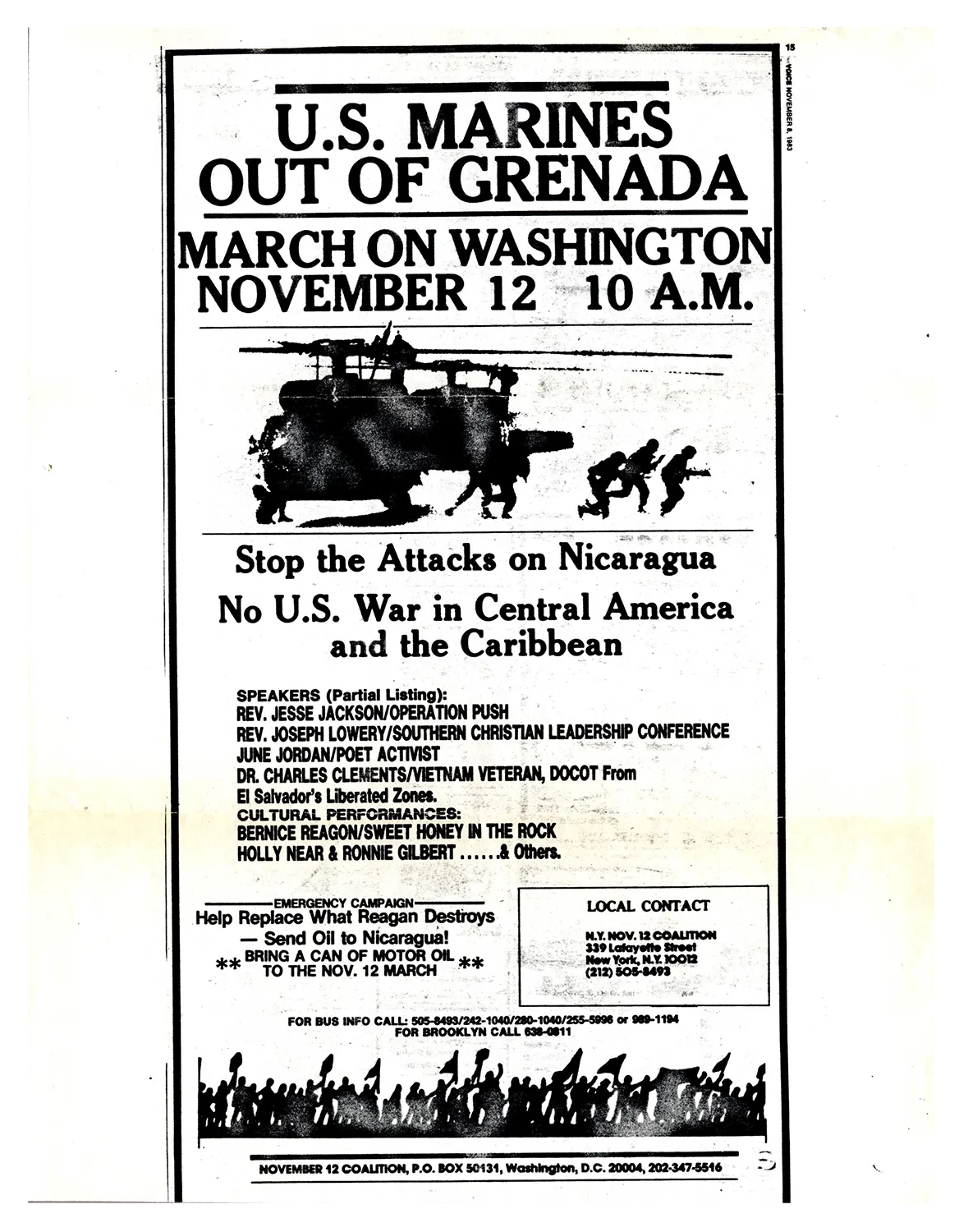

At a protest in Washington, D.C. circa 1986, Jordan spoke out against U.S. imperialism and war in Central America and the Caribbean. The lineup of speakers also included Black lesbian feminist Bernice Reagon of musical collective Sweet Honey in the Rock.

Correspondence and community

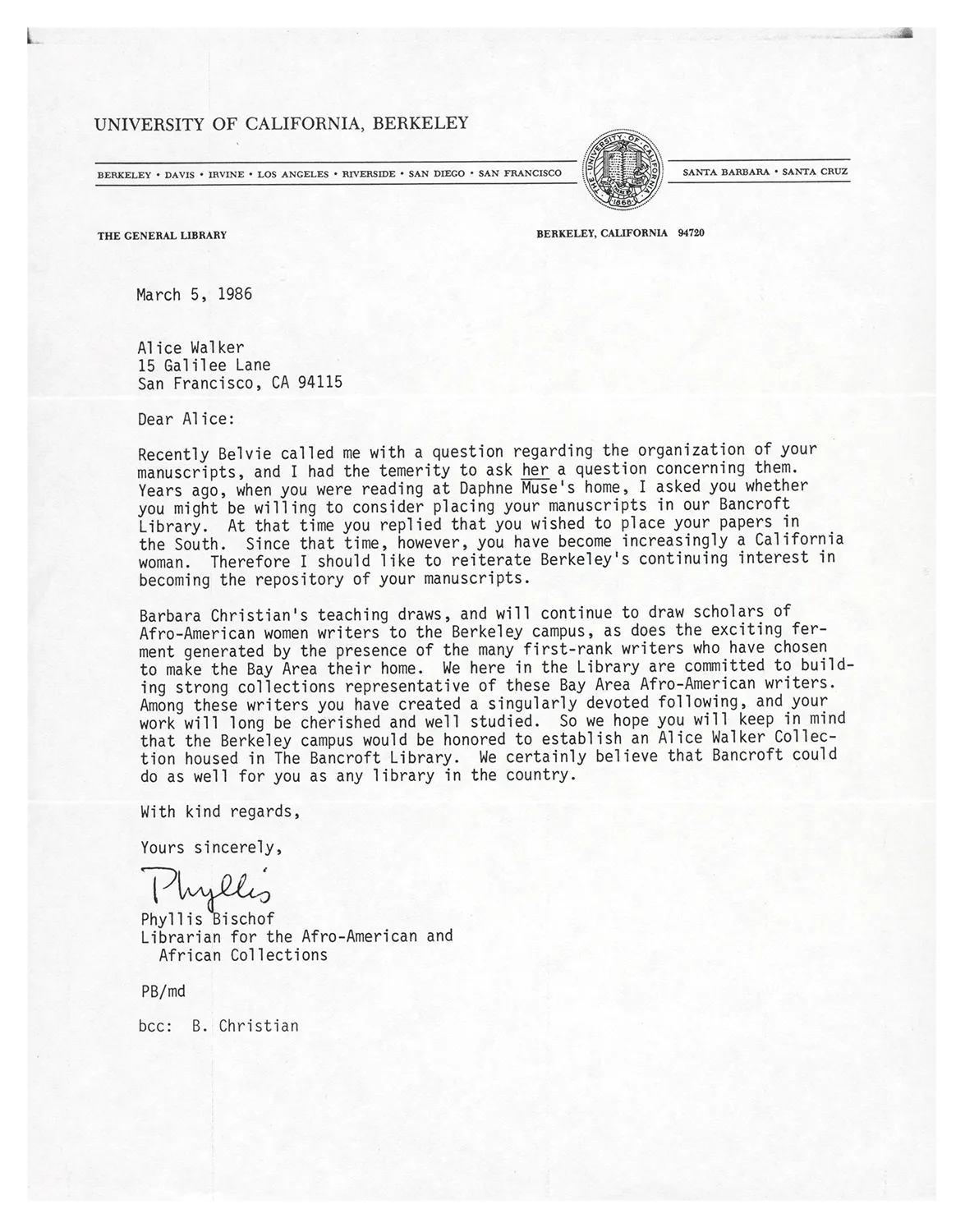

The poets and writers highlighted here are part of a much wider and deeper ecosystem of Black feminists who were thinking and moving alongside one another, offering encouragement and support both in their interpersonal relationships and through the gift of their words and writing. Indeed, Barbara Christian’s and June Jordan’s presence at Berkeley drew African American women scholars and writers to campus, and encouraged UC Berkeley librarians and archivists to collect materials that reflected the lives of Black women authors who lived in the Bay Area.

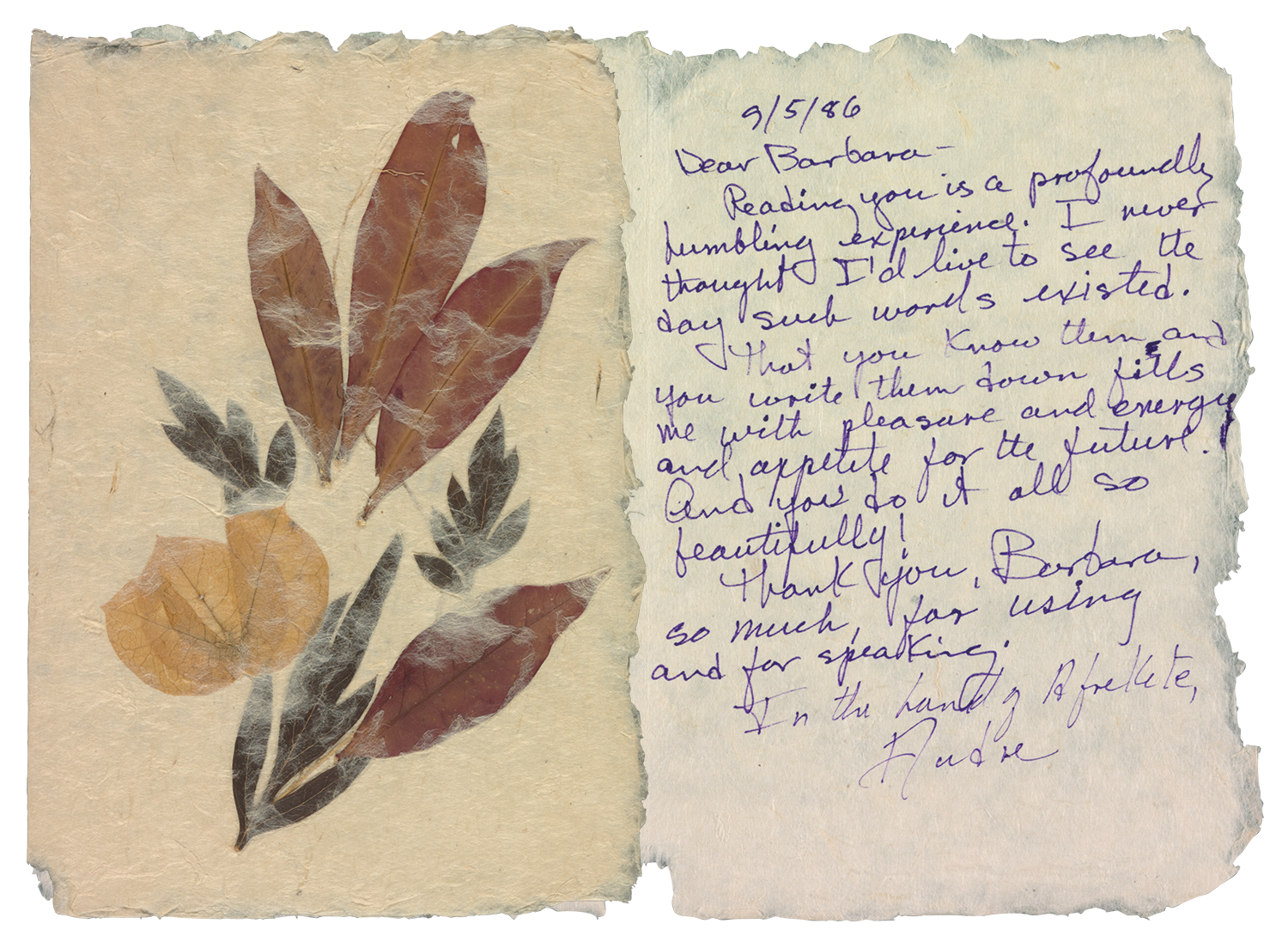

In this personal correspondence, Audre Lorde expresses her gratitude toward Barbara Christian: “Dear Barbara, Reading you is a profoundly humbling experience. I never thought I'd live to see the day such words existed. That you know them and you write them down fills me with pleasure and energy and appetite for the future.” In this correspondence, we can see how luminaries of Black feminism were inspired and sustained by one another’s work.

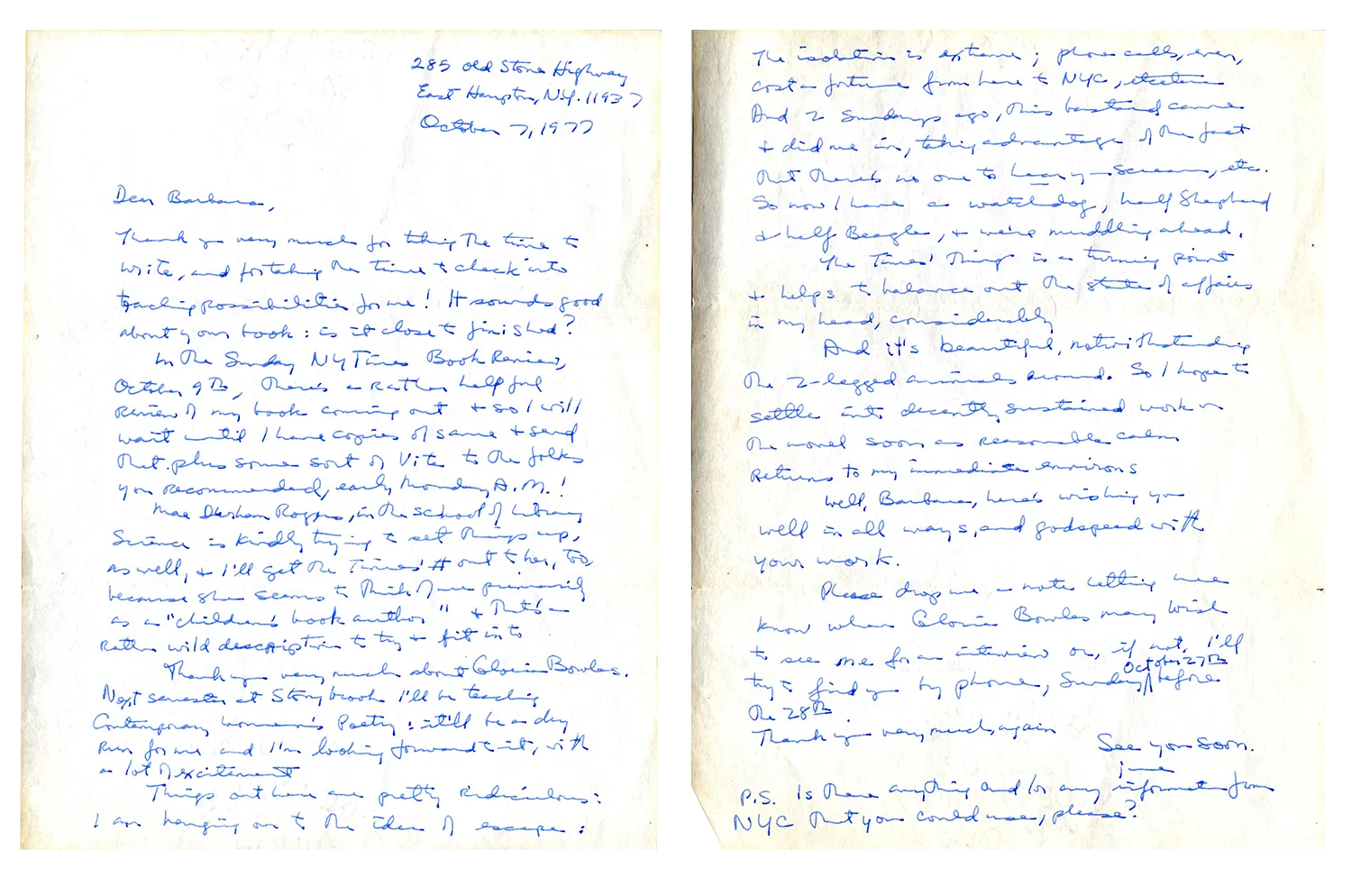

This letter from June Jordan to Barbara Christian illustrates the breadth and depth of their friendship, and how they relied on each other to navigate personal and professional hardships.

“Many thanks to the encouragement and help I received from Nikki Giovanni, Don Lee, and Gwendolyn Brooks. Much love to Gwen Calhoun, Ida Tarver, and my folks. May all joys be in the life of TC who said, ‘Gwan, do it!’” — Diane Bogus (aka SDiane Bogus)

UC Berkeley Librarian Emeritus Phyllis Bischof asks Alice Walker to consider donating her papers to The Bancroft Library. The letter speaks to the work of librarians and community archivists to collect the works of African American women writers. It also mentions activist, writer, and educator Daphne Muse, the inaugural elder-in-residence at UC Berkeley’s Black Studies Collaboratory. The Collaboratory brings artists, activists, archivists, community members, and scholars together to explore and support the work Black Studies does to fight injustice and improve Black peoples’ lives.

Making space in the academy

Black feminists brought waves of change into the institutions where they worked, including UC Berkeley. Often, they faced countless challenges and barriers within these institutions. While they didn’t win every battle, their work made space for future generations, and altered the course of scholarship and higher education in critical ways.

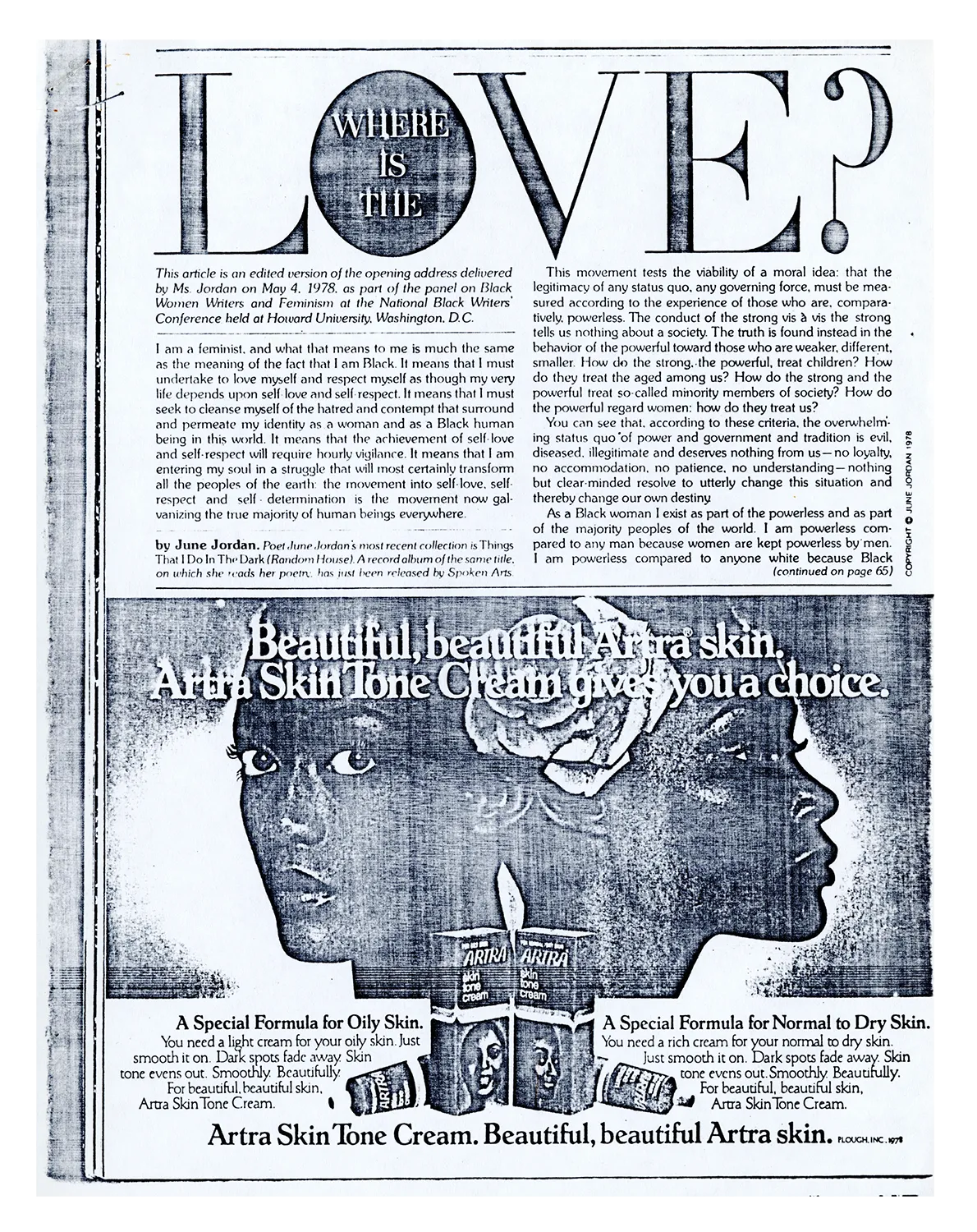

At a historic panel called “Black Women Writers and Feminism” in 1978, Jordan defined Black feminism as an act of love. She said: “I am a feminist, and what that means to me is much the same as the meaning of the fact that I am Black. It means that I must undertake to love myself and respect myself as though my very life depends upon self-love and self-respect. … It means that I am entering my soul in a struggle that will most certainly transform all the peoples of the earth, the movement into self-love, self-respect and self-determination is the movement now galvanizing the true majority of human beings everywhere.”

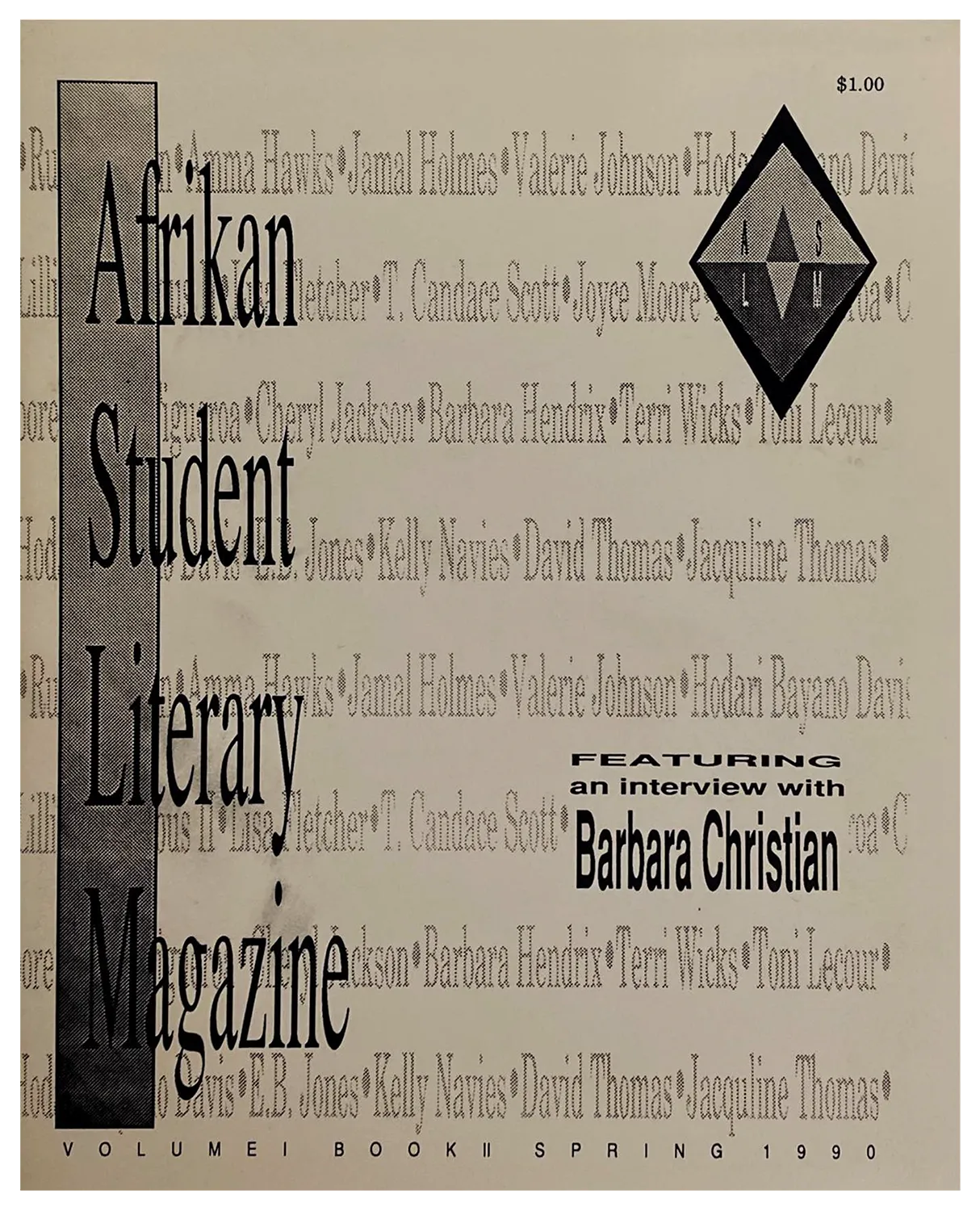

In this interview, Barbara Christian shares her philosophies on teaching, research, writing, and activism. She interweaves her teaching with her political activism, discussing international solidarity and broader movements for social justice.

In this interview, Barbara Christian shares her philosophies on teaching, research, writing, and activism. She interweaves her teaching with her political activism, discussing international solidarity and broader movements for social justice.

Jordan described the inception and accomplishments of Poetry for the People in the merit review statement she submitted to the university administration:

“At the conclusion of the third semester, a core of young poets wanted to make ‘Poetry for the People’ a way of life. And we discussed what to do next. I decided to try and institute a course called ‘The Teaching and Writing of Poetry’. Those students would work closely with me and then they, in turn, would become student teachers of other students, etc. This was something we implemented with reasonable success, I would say.”

“Finally, I may submit my ongoing national and international work as a Poet and Thinker and Political Writer as (ongoing) evidence of my service to University of California at Berkeley.” Ms. Jordan drops the mic.

Poetry for the People anthologies over the years featured the poetry, prose, and artwork of generations of students.

Poetry for the People anthologies, Ethnic Studies Library, University of California, Berkeley.

This collage of Poetry for the People anthologies features the following issues, from left to right, top row:

WHO SAYS THE RIGHT TO LOVE DOESN’T DESERVE A MOVEMENT?, Fall 2004; Whose Country Is This Anyway?, Spring 1995; Survival Take a Verse,Fall 1998; Venus, Spring 2003; IN POETRY WE TRUST: student poets spit their peace, Spring 2003; Mahfouz: Our Right to Our Words, Spring 1998; The Power of the Word; 1992: Soldiers of All Colors: Steppin to Our Minds,” Berkeley High Anthology 1998; NO VOICE NO CHOICE NO COUNTRY IS THIS WHAT WE WANT?, 1993; POETRY SHOULD RUN FOR OFFICE, 2004;

Left to right, second row: What Now?, 1991; POET: Leaves an Impression, Berkeley High Anthology, 1996-1997

Left to right, third row: profiles in conflict, Spring 2002; Write or Be Erased, Spring 2005; we are the ones we have been waiting for, Spring 1999; Poetry for the People in a Time of War, 1991;IN A LIGHT THIS BEAUTIFUL, Fall 2000; MY OAKLAND SINGS, The June Jordan Poetry Prize Anthology, 2004-2006; tHIS iS HOW WE FLOW, Spring 1999; 71 SECONDS OF FREEDOM, 1997; …ihe anyi ga ekwuriri…lo que debemos que decir…, Spring 2000; poetry for the people presents poetry in a Season of Love, 1994

Left to right, bottom row: AND OUR EYES WERE WATCHING, Fall 2005; Constructing the New Democracy Spring 2001; SPEAK ON IT! SMASH THE STATE: THE SECOND COMING, Spring 2002; MY SKIN: A CANVAS OF POEMS, Fall 2003; WITNESS: A COLLECTION OF REVOLUTIONARY POETRY BY BERKELEY HIGH AND UC BERKELEY STUDENTS, Fall 1999; Love Lifts Borders, Spring 2006;i have seen concrete disintegrate, Spring 2009; UNLEASHED, Berkeley High School 2002-2003 Anthology; POETRY IN A TIME OF GENOCIDE, 1993

Recognitions

Thanks to the contributors who lent their expertise to the development of this project: Lorna Kirwan, Chrissy Huhn, Tor Haugan, Jesse Loesberg, Michael Lange, Nathaniel Moore, Lisbet Tellefsen, and Tiffany Grandstaff, as well as the staff of the Ethnic Studies Library, The Bancroft Library, and the Library Communications Office. Thanks to Professors Leigh Raiford and Tianna Paschel, the Black Studies Collaboratory, and the Department of African American Studies & African Diaspora Studies for inspiring us.

Editor’s note: This article was updated from its original form.